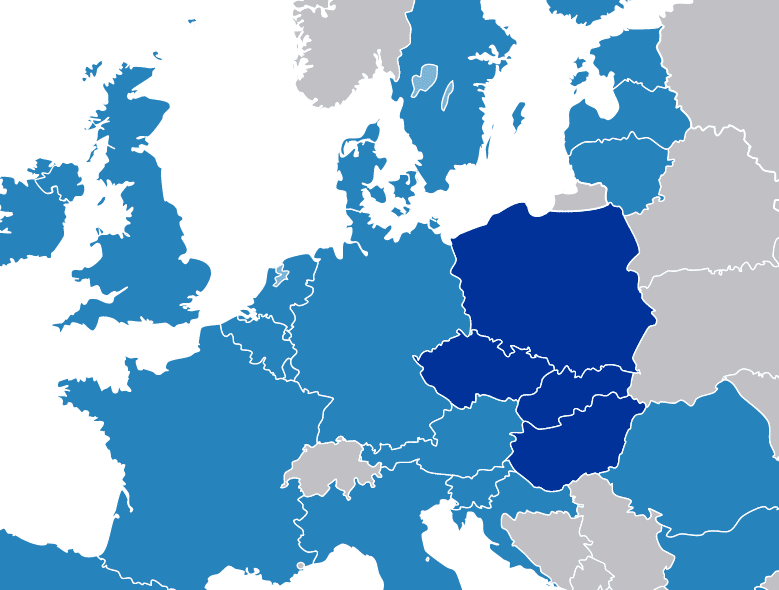

Drug policy varies greatly among European countries, despite common foundations in UN treaties or EU strategies. In this article I’ll review syringe service programs (SSPs) in four East-Central European countries—the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland and Hungary, collectively known as the Visegrád Group—to show how politics impact harm reduction.

The Overview

The Civil Society Forum on Drugs, an expert group of the European Commission, published a report a year ago on the implementation of services for people who use drugs (PWUD). The report reveals discrepancies in the accessibility and quality of 12 examined interventions, with the greatest contrast for SSPs found among the Visegrád Group.

Asked to rate accessibility of SSPs in their country, surveyed Czech professionals in the field gave a high score: 8.9 out of 10. Poland returned a medium score of 4.7. Professionals in Slovakia (3.5) and Hungary (just 1.8) gave low scores for SSP access.

Analysis of annual reports of SSPs shows that they are available in 65 percent of Czech cities, 21 percent of Hungarian cities, 15 percent of Slovak cities and only 7 percent of cities in Poland.

According to European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction data and information acquired directly from the services, 2017 numbers for sterile syringes distributed per PWUD were: 199 in the Czech Republic, 184 in Slovakia, 65 in Hungary and only 35 in Poland.

Where do these dramatic differences come from?

My experiences in drug policy and harm reduction research in the region suggest that the internal functioning of SSPs is similar. They hire similarly educated personnel, adhere to similar values and principles and have congruent procedures.

But criminal law around drugs varies greatly. In the Czech Republic, possession of small amounts constitutes an administrative offence, subject to a small fine. In Hungary, even drug consumption is punishable by up to two years in prison.

So it seems plausible to seek reasons for access discrepancies outside the services themselves.

The Czech Green Island

Czech public opinion still perceives drug dependence as a blameworthy life choice, but policy seems to follow a different path, as reflected by the 2010 decriminalization of small-scale possession. Yet regressive attitudes persist among police and healthcare professionals. PWUD are still often stigmatized and refused access to healthcare services.

But decriminalization has likely contributed to increased SSP access. Service coverage for people who inject drugs rose by 7 percentage points between 2012 and 2013 and has remained relatively high and stable since, at approximately 75 percent. Decriminalisation also helps the continuity of providers’ relationships with clients, who are not incarcerated for possession any more.

The total budget for Czech SSPs increased by approximately 60 percent from 2008-2017.

Harm reduction enjoys sound political support from the central government. In 2018, 14 percent of total drug policy expenditure was dedicated to harm reduction—more than the budgets for drug prevention and treatment combined. The total budget for Czech SSPs increased by approximately 60 percent from 2008-2017. Significant resources are also allocated to research in this area, and the country’s prime minister personally visits services to get familiarized with their work.

The fragmentation of the Czech care system nevertheless hinders holistic care and client support. Agencies typically fail to work with one another and SSPs experience excessive bureaucracy. Employing medical personnel also tends to be challenging as a result of a labor scarcity.

Yet significant political support for harm reduction means that funding is stable and organizations can plan strategically.

A Bleak Outlook in Slovakia

Most Slovaks believe that the most effective method of addressing drugs is through criminal law, and this is reflected in the country’s policies. That said, politicians here aren’t really interested in this area. Several years ago, responsibility for drug policy was transferred to an institution of lesser significance and political influence. Populist politicians prefer to focus on sexier issues than PWUD.

Harm reduction plays a marginal role here. The most up-to-date financial data, from 2006 [sic!], shows that the harm reduction expenditure was approximately 10 percent of the money spent on prevention and treatment.

Service access is very low. For example, medication-assisted treatment (MAT) covers only 12 percent of people who use opioids. There are no shelters or protected workplaces for PWUD, and lack of health insurance disqualifies you from hepatitis C treatment.

SSP clients sometimes experience violence from locals.

Harm reduction organizations must devote a significant share of their time to grant- and report-writing, which negatively affects their relationships with clients. Funding is unstable and highly dependent on political whims. Corruption in state financing institutions additionally threatens organizations. Resources are insufficient, and several SSPs recently shut down. Regulations on grant spending prevent flexibility to meet clients’ needs. At the moment, only three SSPs remain.

What’s more, SSP clients sometimes experience violence from locals. Conflicts can erupt between local communities and politicians on the one side, and SSPs on the other.

An Inferno in Hungary

One measure of how bad things are here is that 64 percent of Hungarians do not want to have a person with drug dependence as their neighbour—14 percentage points more than feel that way about a person with a criminal record. Drug policy seems to be fueled by moral panic and strong conservatism. A “drug-free” Hungary by 2020 is a primary aim. Facing routine prejudice, PWUD are often denied access to public services.

In Hungary, you can be imprisoned for the mere use of controlled substances (as opposed to possession). Diversion (treatment instead of prison) is only permitted once every two years, resulting in frequent incarceration.

Harm reduction comprised just 4 percent of the drug policy budget, of which 75 percent was spent on law enforcement.

SSPs’ legal position is uncertain—whether they’re permitted depends on political will and interpretation of the law. Many politicians like to destroy organizations that they consider hostile to their worldview.

Financial data from 2007 (last available) show that the harm reduction expenditure comprised just 4 percent of the total drug policy budget, of which 75 percent was spent on law enforcement. And the harm reduction budget was significantly cut in 2011.

SSPs struggle with extensive red tape and political and financial instability. The term “harm reduction” has not appeared in public tenders for the past few years, with services forced to “smuggle” such interventions in other support categories.

In 2014 and 2015, Hungary’s two largest SSPs were closed thanks to local politicians’ actions. In September 2019, Prime Minister Viktor Orban announced further drug policy restrictions. Given his unexpected defeat in October municipal elections, however, the future is unclear.

Moralizing in Poland

Almost 80 percent of Poles think that consumption (not possession!) of cannabis should be illegal. Medical professionals frequently deny people who inject drugs access to healthcare, sometimes even when a life is at risk.

Criminalization of drug possession harms the continuity of services’ relationships with clients due to frequent incarceration. Despite actions by the Chief Sanitary Inspectorate against shops selling “legal highs” and moralizing speeches following poisonings, drug policy doesn’t much interest Polish politicians. Indeed, none of the major political parties included drug policy in their last manifestos.

Drug policy, such as it is, is focused on law enforcement and a strong abstinence paradigm. Many harm reduction services staff see harm reduction as being in competition with other public services, and think that the state funds harm reduction only because of international control, especially by the European Union.

The number of Polish SSPs dropped by almost half from 2002-2017.

Although harm reduction is officially considered one of the pillars of drug policy, it remains on the margins. The vast majority of resources are allocated to prevention and long-term inpatient treatment based on the therapeutic community methodology.

In 2019-2020, a planned drug policy budget raised from gambling tax allocates five times more money to drug prevention than to harm reduction. Funding is based on short-term tenders, resulting in high instability.

An inefficient care system covers only a fraction of people in need. For example, in 2017, only 18 percent of people using opioids were on MAT. Harm reduction organizations often struggle with unreasonable bureaucracy and public health funders’ strict reporting requirements, which reflect institutional distrust. The necessity of low-threshold access is not widely understood.

The number of Polish SSPs dropped by almost half from 2002-2017. Local communities often have hostile attitudes toward any organization supporting marginalized groups.

Conclusions

Policies, in combination with public attitudes, overwhelmingly determine harm reduction’s prospects in the Visegrád states. In the Czech Republic, structural factors are significantly facilitating effective operation of SSPs. In the other three countries, they hinder the work.

The data suggest that Hungarian harm reduction organizations endure the worst working conditions. The current situation is especially disappointing when, in the 2000s, harm reduction enjoyed strong political support and developed dynamically in Hungary. When the Orbán administration came to power in 2010, one of its first actions was to attack harm reduction and cause its collapse.

Yet the examples of Slovakia and Poland show that neglecting and ignoring drug policy results in a situation which is only slightly better than open war against harm reduction.

This article is based on the findings of Iga Kender-Jeziorska’s study—”Needle exchange programmes in Visegrad countries: a comparative case study of structural factors in effective service delivery”—published in Harm Reduction Journal in September 2019. Harm Reduction Journal is an open-access, peer-reviewed publisher of research into drugs and many intersecting areas. Filter is proud to partner with Harm Reduction Journal to help bridge the gap between research and public understanding.

Image showing European Union and Visegrád countries by CrazyPhunk via Wikimedia Commons.

Show Comments