Harm reduction shouldn’t just seek to reduce the harm caused by drugs, but also the harm caused by drug policies,” tweeted Alex Wodak, a leading drug harm reduction advocate in Australia, last month. Harm reductionists worldwide have long shared this view.

Shouldn’t this be equally true when it comes to tobacco? That not only should we seek to reduce harm caused by smoking or chewing tobacco, we should also seek to reduce harm caused by tobacco control policies? Because believe me, those harms are real and severe.

Progress will be difficult. The relationship between tobacco harm reduction advocates and tobacco controllers legislating against snus and vaping is badly strained. We both started with the same desire to reduce the number of people suffering from tobacco-related illnesses. That was the purpose of the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

Where we have diverged is over what we are willing to do to people in order to stop them smoking.

International Punishments for Smoking

There are some extremes that both sides oppose. For example, it is unlikely anyone today would support the use of the death penalty for smoking tobacco. Ming Dynasty Emperors in the 1630s thought execution was an acceptable deterrent for possessing or using it. Perhaps Emperor Chongzhen had a dream one night showing him the future when China would have the most smokers in the world, with 1 million of them a year dying prematurely as a result.

But how about something less extreme? Being separated from your child, for many people, is a living hell. Forcibly removing a child from their parent can be traumatic, and can lead to ongoing psychological distress for both parent and child. Surely no one today would condone removing children just because the parent smoked?

Actually, the fact that a parent smokes has been used to influence custody decisions, particularly when the child had asthma. In some jurisdictions, adoption applications from smokers are rejected. Smoking is also used as a reason to deny people access to fertility treatments that could help them have a child.

This was a brutal signal that Australian tobacco control had fallen into a draconian abyss.

Another way in which parents who smoke can be separated from children is through incarceration. Obviously, people only get incarcerated if they’ve committed a crime, or are accused and awaiting trial. No one is sent to prison for smoking tobacco. Or are they?

In June 2017, a Tunisian man was jailed for a month for smoking in public during Ramadan. And a few other countries are threatening smokers with prison sentences; for example, South Africa is considering a three-month sentence if a smoker lights up in a public no-smoking area!

A sign in Japan threatens a fine for smoking in the street.

To compound matters, many countries fail to distinguish between smoking a cigarette and vaping, and they’re fining people for doing either in smoking-restricted areas.

Thailand is notorious among vapers who travel for its ban on even possessing an electronic cigarette. In 2017, a Thai woman was violently arrested when a vaporizer and a bottle of e-liquid were found in her car. In January this year an elderly Israeli couple travelling in Thailand were detained and fined for vaping.

In 2011, West Australian police raided the online Heavenly Vapours operator Vincent Van Heerden’s home. His stock was confiscated and he was convicted and fined for possessing and selling vaporizers and non-nicotine e-liquid. This was a brutal signal that Australian tobacco control had fallen into a draconian abyss.

Over the Tasman Sea, where I live, the New Zealand Government, which historically has entertained Australia’s advice, at first said nicotine e-liquid was banned. The two countries had a loose agreement to align their tobacco control policies. Thankfully, New Zealand veered away from prohibiting smokers’ access to hugely risk-reduced alternatives to smoking.

Unintended Consequences of Excessive Taxation

New Zealand and Australia are aligned, however, on gouging taxes. Tobacco downunder is the most expensive in the world; for instance, a leading-brand pack of 20 cigarettes costs AU$28.95 (US$20.92) in Aussie.

As we see in many other areas of drug policy, badly conceived laws have negative unintended consequences. Unsurprisingly, trade in illicit, untaxed tobacco is booming in Australia, while overall smoking rates are barely shifting, and for some groups are increasing.

People instead began looking for cheaper tobacco and chop chop. But the unintended consequences didn’t stop there.

The equivalent illicit market in NZ has been limited, due to our being a relatively small island nation with vigilant border control. Bringing back cartons of duty-free cigarettes from abroad has long been a common way for NZ smokers to get around the high tax on tobacco at home.

In 2015, however, the duty-free allowance was cut from 200 to 50 cigarettes per person, and customs also cracked down on carrying tobacco other than for personal use. Months later, in 2016, New Zealand applied yet another tax hike to tobacco. A pack of 20 of the same leading-brand cigarettes now costs NZ$28.90 ($US19.92)—almost identical to Australia. That turned out to be a tipping point.

Legal tobacco was now unaffordable for many more already financially stretched people. Did they miraculously just quit, like public health campaigners said they would? No. They either had tried and tried and hadn’t been able to quit, or they didn’t want to stop smoking.

People instead began looking for cheaper tobacco and chop chop (home grown). But the unintended consequences didn’t stop there.

A craze of aggravated robberies of convenience stores and petrol stations for tobacco began. Gangs of youths drove stolen cars up to or into shops. If shopkeepers wouldn’t open the locked tobacco cupboard, they were threatened and occasionally bashed until they did. All over the country, people began to be caught, fined and sent to jail for stealing, selling or smuggling tobacco.

Lack of affordable tobacco for people who can’t stop smoking, or don’t want to stop—a form of financial prohibition—became a significant new cause of crime, just as general drug prohibition has been shown to drive violence and crime.

Criminalization and Racial Targeting

Some other extreme tobacco control policies that Australia has already implemented are being heavily pushed in New Zealand. Criminalizing and fining smokers who puff up in cars when under-18s are present is one.

New Zealand has not yet fined a smoker for lighting up in a legally designated smokefree area. We used to understand that smoking is a highly addictive behavior, so fining people for smoking could have seemed a bit unsympathetic and that’s not very Kiwi. Being downright psychopathic towards smokers would have lost us public support for the Smokefree 2025 dream (a smoking prevalence of 5 percent or below). The onus, and if necessary fines, were instead put on organizations and employers. It was up to them to make it clear when an environment was smokefree. Similarly, it is retailers who sell tobacco to minors—not the minors trying to buy the tobacco—who are fined.

The new approach heads in the opposite direction. Criminalizing people who smoke, in their vehicles in the presence of a minor, for instance, represents a complete paradigm shift from provision of care to policing health. It reframes smoking as a criminal act rather than the public health problem that it is. It denies smokers their rights under our Health and Disability Act to be treated with respect, to be supported to choose between a range of evidence-based interventions, like vaping.

Māori mothers will be disproportionately penalized.

Criminalizing smokers also risks widening the social and economic disparities between the politically dominant white population and the large Māori (indigenous) and Pacific Island groups in New Zealand. Due to colonization and historical and systemic discrimination, Māori are over-represented among the poorest and most marginalized groups. As a result, Māori women have NZ’s highest smoking rates (38 percent) of any adult ethnic male or female group. Rates are highest among 18–to-50-year-olds—that is, people who tend to be parents.

A further problem for Māori is exacerbated by a move toward policing smokers: racist profiling by police. Half of the women imprisoned in New Zealand are Māori. If the government moves to fine smokers, it’ll be Māori mothers, likelier than men to be driving children around, who are disproportionately penalized. And what happens if you can’t pay your fines? Imprisonment.

People Can Know Better

Surveys presented to politicians suggest that up to 95 percent of people support banning smoking in cars when minors are present. The participants, however, were given limited tick-box questions stripped of context. They were not told of the potential harm the policy could do, especially to Māori. They were not told that Māori women smoke at three times the rate of their white female counterparts, and are therefore disproportionately targeted by such a proposal.

The politicians weren’t told of the glaring biases inherent in the surveys: that the questions were leading, that the people who would be hurt the most by the results were under-represented among respondents; and that social desirability bias would have been through the roof.

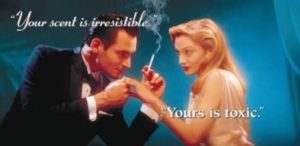

Only 16 percent of New Zealanders smoke. After 40 years of anti-smoking campaigns like the one above, designed to destroy any shred of empathy for people who smoke, a biased survey could probably net 95 percent support for the harshest of punishments, including taking children away from their parents.

I refuse to believe, however, that fully informed New Zealanders would support a policy that will become just another gateway to prison for young, poor and marginalized Māori.

The widespread support for legalizing harm-reduced alternatives to smoking shows that the New Zealand public are woke on this. A harm reduction approach is seen as sane and reasonable. It’s also seen as logical to give the new way a go. To do that we’ll need to make sure the poorest and most vulnerable high-smoking groups get access to risk-reduced alternatives. Public health campaigns, too, could switch—from stressing how tough it can be to quit, to showing how easy it can be to vape instead.

Consistent with a harm reduction approach, the draconian policies should be binned. Why hurt people if you don’t need to?

Show Comments