The sciatica pain jolting down my right leg was so severe that it was hard for me to function. All I wanted was to get the marijuana that scientific and anecdotal evidence told me would help—as permitted since 2014 in my home state of New York.

But getting certified for New York’s Medical Marijuana Program (MMP) proved complicated, time-consuming, costly and infuriating. The experience suggested that the state agencies behind it don’t actually want patients to get the drug.

“We believe healthcare is a right, not a privilege,” states the message when you call the Ryan Adair Clinic in Harlem. It’s one of the reasons I like the clinic. The other is my primary care physician, Dr. Hack.

But she told me she couldn’t certify patients for medical marijuana because the clinic receives funding as a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), meaning it’s obliged to comply with federal laws. (The clinic’s executive director, Charles Shorter, later confirmed to me that attorneys had advised him not to allow physicians to certify patients.) What’s more, Dr. Hack said, she wasn’t even allowed to mention the option of medical marijuana to patients.

FQHCs are intended to provide healthcare to underserved and uninsured populations. These clinics serve a disproportionate amount of people on low incomes, people of color and migrants. So this restriction means many poor people of color are denied access to medical marijuana—yet another way that healthcare structures reinforce racism.

Dr. Hack did, however, refer me to the Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine at Mount Sinai in Manhattan. I didn’t want to see a doctor who didn’t know my history just to get medical marijuana. But the pain was so bad I made an appointment.

In this climate, thousands of doctors simply won’t register to certify patients.

There, the doctor who examined me decided I was eligible for medical marijuana due to my sciatica diagnosis. But he was skeptical about marijuana’s therapeutic value. He said there wasn’t enough evidence that it helps control pain and that more studies were needed. I told him he should search PubMed. Then he backtracked and said perhaps there was a 50-50 chance that it would work for my pain.

Skepticism about the efficacy of medical marijuana is common among doctors. I asked Sunil K. Aggarwal, MD, PhD, the co-director of the AIMS Institute and a cannabis expert, why this is.

“Because it’s a Schedule I Drug which cannot, outside of research trials, be prescribed but only medically authorized or recommended under state laws,” he explained. “The stigma associated with this outrageous and false classification makes routine medical use difficult. Also, most physicians have not seen it being used in their training and they aren’t taught how to find, read, and analyze the voluminous scientific evidence that already exists showing that cannabis is medically effective.”

In this climate, thousands of doctors simply won’t register to certify patients. And many New York doctors who do register refuse to have their names listed on the MMP website. They don’t want to be known as “pot doctors.” In a state of 20 million people, just 59,327 certified patients and 1,697 registered practitioners participate in the MMP.

An Unethical Application Form

The Mount Sinai doctor handed me a two-page form. Before I could be certified, I had to sign a Medical Marijuana Agreement. What?

The form required me to agree to a number of statements. For example, that marijuana “is a strong drug and there may not be sufficient medical evidence to confirm its usefulness and safety in my type of chronic pain.”

Yet marijuana does treat pain and it is relatively very safe. Safer, for example, than opioids—the reason opioid replacement was added as a qualifying condition to the MMP this year.

The entire agreement was written in the spirit of Reefer Madness. I was convinced that such an infringement of rights couldn’t be legal.

The form got worse. The third paragraph stated that a side effect was “death.” There isn’t one documented case of a person dying from marijuana use alone.

Next up, I had to initial a set of 15 “conditions of treatment.” As I scanned them, I was dumbfounded. I had to keep the drug in a locked cabinet. I shouldn’t drive or “make important decisions” for four hours after taking it. Especially outrageous were these two conditions: “I will not use any illegal drugs at any point and will submit to random urine drug screening upon request” and “I will not use MM in conjunction with opioids, benzodiazepines or alcohol.” Who were Mount Sinai to tell me I couldn’t have a glass of wine?

The entire agreement was written in the spirit of Reefer Madness. I was convinced that such an infringement of rights couldn’t be legal (and I contacted the New York Civil Liberties Union for comment). But I signed it because I was desperate to deal with the continuous pain in my leg.

Chronic pain patients are vulnerable to signing away their rights to access treatment. They often pay lots of money, too. The application fee for the MMP is $250. Why? No other medication has an enrollment fee, and this represents yet another barrier for lower-income patients. (Not all New York clinics charge the fee, however. Dr. Julia Arnsten, chief of Internal Medicine at Montefiore Medical Center, told me that her clinic waives the fee in recognition that many patients, particularly those on Medicaid, simply cannot afford it.)

Shortcomings That Were Always Apparent

New York’s Medical Marijuana Program launched in 2016, supposedly to speed up the process of patients accessing medicine.

Prior to this launch, Compassionate Care NY, a medical marijuana advocacy group, informed Governor Cuomo and the NY Department of Health that the proposed regulations would make it difficult for doctors to prescribe medical marijuana and difficult for patients to get it. The regulations were overly restrictive and the costs too high, they said. It was designed to fail.

Not allowing patients to procure the plant is inexcusable. The reasons relate to profits, politics and prejudice.

Immediately after the program’s launch, Compassionate Care worked with state legislators to introduce a series of bills to address the problems they already had publicly identified: Not enough doctors registering, too few qualifying conditions, a lack of dispensaries, limits on the types of medicine, and steep costs. Several of these bills passed: More qualifying conditions were added, nurse practitioners and physician assistants were permitted to certify patients, and more dispensaries were opened.

But the affordability problem remains. New York State Health Commissioner Dr. Howard Zucker has excluded any forms of whole-plant material that could be smoked. Only tablets, liquids and oils that can be vaporized or placed under the tongue are available. Unlike relatively cheap natural marijuana, processed extracts are expensive. Not allowing patients to procure the plant, however they choose to ingest it, is inexcusable. The reasons relate to profits, politics and prejudice—smoking marijuana is still seen as a deviant behavior.

Chaos and a Long Wait for Care

When my registration forms arrived in the mail almost three weeks later, I immediately noticed an error. The Mount Sinai doctor had put my last name as my first name. I called and was told he would fix it.

His careless typing set off a cascade of confusion. The patient registration instructions explicitly stated, “DO NOT register using incorrect information as this might delay your registration.” To get into the Medical Marijuana Data Management System, I had to create a My.Ny.Gov. ID. For days, I checked to see if my name had been corrected but it hadn’t—even though the clinic staff kept insisting that it had.

I eventually threw in the towel and called the hotline in Albany for help. The ensuing saga involved the cancellation of my first patient certificate and the issue of a new one; the creation of a whole new My.Ny.GOV ID; and then the failure of that website to allow me to re-submit my information.

Now I was livid. I called Albany again, no one answered, and I left a nasty voicemail. The next day a rep did answer. She asked which browser I was using.

“Safari.”

Oh, that’s the problem, she responded. I needed to use another browser—probably Google Chrome. I exploded: Are you fucking serious? This is New York in 2018. I have to download another browser just for your program to work?

On the verge of tears, I decided I would just do the telephone registration option provided for people with “no computer access.” Until it turned out that that would take even longer to be approved for the MMP, because I would have to sign an attestation form and send it via snail mail.

Furiously aware of the unfairness to those who don’t have computers or computer skills, I downloaded Google Chrome, and managed to complete the application and print out a temporary card.

A Visit to a Cannabis Dispensary

After about a month of unnecessary pain, I was finally able to visit the Columbia Care Cannabis Dispensary in Union Square. The first person I saw there was a guard, wearing a shirt emblazoned with “Armor Security.”

Marijuana in the dispensary was on lock-down, but illicit marijuana is for sale all over Manhattan.

He unlocked the door, let me in, and then locked the door behind me. I waited in what is called a “man-trap,” a sort of air-lock separating the entrance from the waiting room, while he checked my temporary ID card. Only then did he unlock the door so I could enter the dispensary.

It felt like going into a speakeasy. Marijuana in the dispensary was on lock-down, but illicit marijuana is for sale all over Manhattan. I saw several people openly smoking joints as I approached Columbia Care through Union Square Park. It’s absurd.

The waiting area was all white brick and brown paneling. Patients sit on blue benches and cool, modern chairs. Green plants in boxes (no, not those plants!) dotted the floor and white neon lit the space like an art gallery. Despite the pan-tilt-zoom security cameras watching from the ceiling, the vibe was canna-zen.

Until I had to sign a “Patient Waiver of Liability and Hold Harmless Agreement.” The sentence that disturbed me most? “I voluntarily assume full responsibility for any risk, loss, damage or personal injury (including death) that I sustain as a result of being a customer of Dispensary and/or my possession or use of marijuana.” There it is was again: the death-threat.

Until I had to sign a “Patient Waiver of Liability and Hold Harmless Agreement.” The sentence that disturbed me most? “I voluntarily assume full responsibility for any risk, loss, damage or personal injury (including death) that I sustain as a result of being a customer of Dispensary and/or my possession or use of marijuana.” There it is was again: the death-threat.

Columbia Care is the largest multi-state medical cannabis operator in the US, with a total of 33 licenses in 13 states including Puerto Rico. CEO and co-founder Nicholas Vita was a strategic advisor at S.G. Warburg, a global investment bank. The Columbia Care website boasts of employing alumni of Goldman Sachs and Fidelity Investments, and showcases how rich, white, male corporate America has cashed in on legalization.

A locked glass door opened and Chip Walker, a genial PharmD, called my name. We walked through to the Orwellian-sounding “patient education room.” With expertise, he explained how THC and CBD work and showed me the different forms: vaping oil, tincture and tablets. Chip recommended two cannabis oil products and demonstrated how to use the vaping pen.

This pen automatically locks so that another hit isn’t possible for 15 minutes. I was told the feature was added so that patients can’t take multiple hits to “get high.”

One 0.4ml vaporization cartridge cost $100. I needed two. The vaping pen was $10. Add the application fee, and my total out-of-pocket costs for medical marijuana were $460. There was no way after all I’d been through that I wasn’t going to buy the vaping products, despite the outrageous price tag. Chronic pain clarifies financial priorities.

I eventually got the medication I needed. But experiences like mine confirm that New York’s Medical Marijuana Program is disastrously conceived and operated, for both patients and healthcare providers. Medical marijuana remains out of reach for thousands of less privileged patients who have a qualifying diagnosis but are left to suffer.

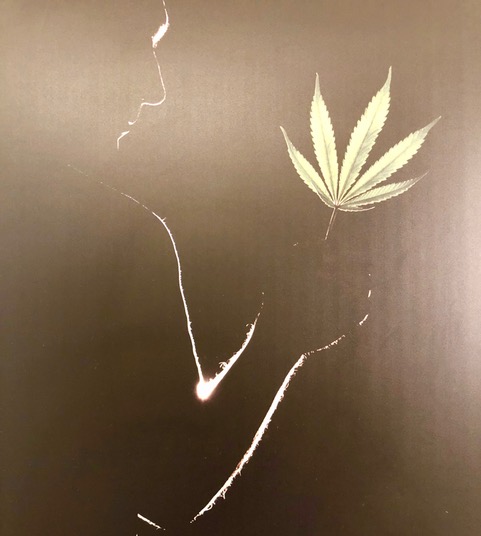

All images: Helen Redmond

Show Comments