On December 18 the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report on fentanyl and methamphetamine sales by Mexican transnational drug-trafficking organizations—their supply chain and distribution networks, money-laundering methods and of course what the United States government is doing about it. It mostly reiterates findings already reported by the Drug Enforcement Administration without quite confirming them, and appears to be the first time GAO has gone undercover as someone looking to buy drugs online.

The report, “Illicit Synthetic Drugs: Trafficking Methods, Money Laundering Practices, and Coordination Efforts,” was mandated by the Biden-era Preventing the Financing of Illegal Synthetic Drugs Act, although it appears to be arriving a few months past deadline. The Act was sponsored by Rep. Monica De La Cruz (R-TX), who had presented it as a fentanyl crackdown necessary to protect border communities.

It required GAO to “carry out a study on illicit financing in connection with the trafficking of synthetic drugs”—namely fentanyl, methamphetamine and their precursors and analogs. And Captagon, a long-discontinued psychostimulant medication that is not relevant to the US drug supply. Its only appearance in the report is in a couple of footnotes, where the authors state that they were legally compelled to include Captagon in their review but that it is not relevant to the drug supply.

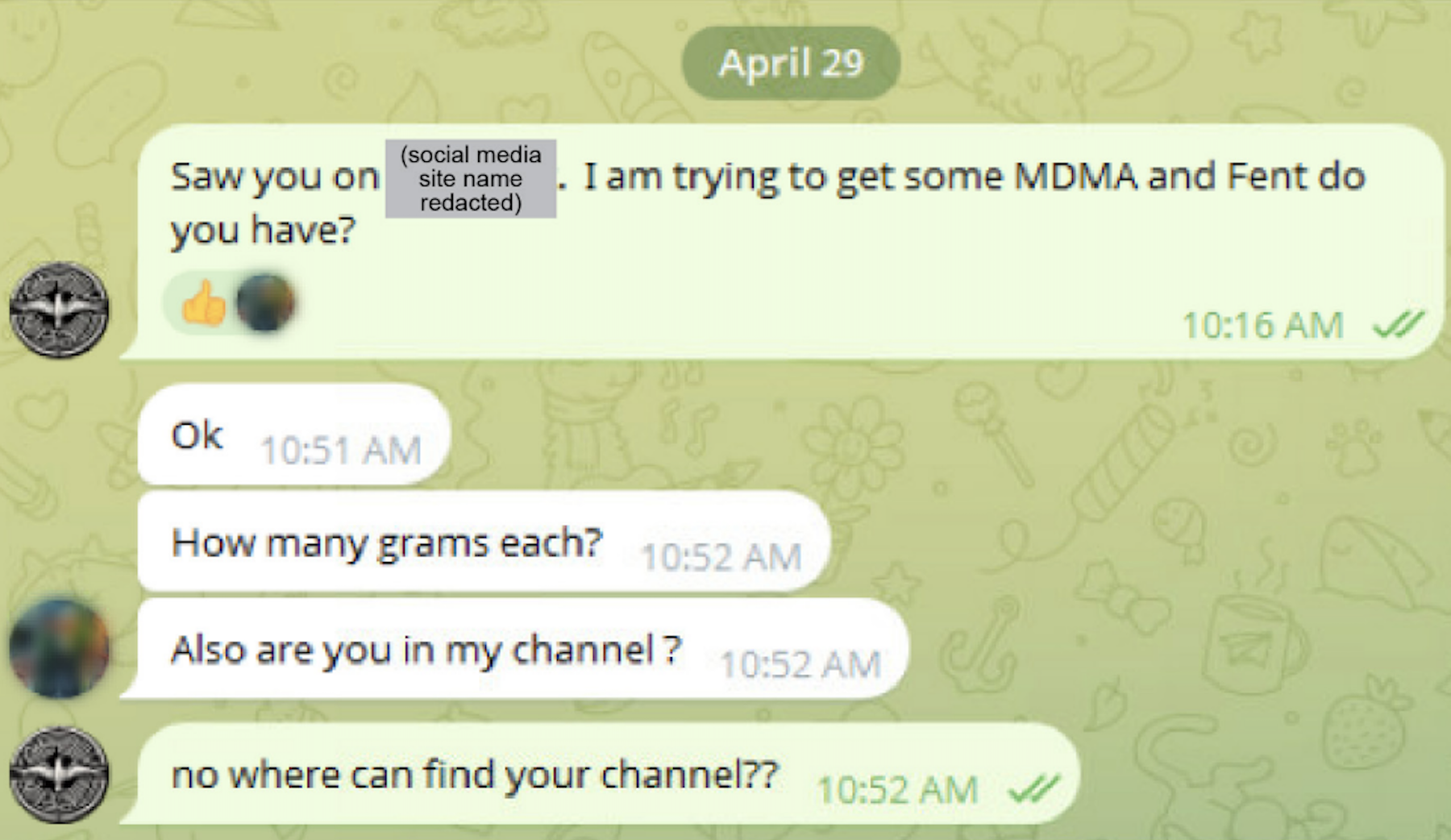

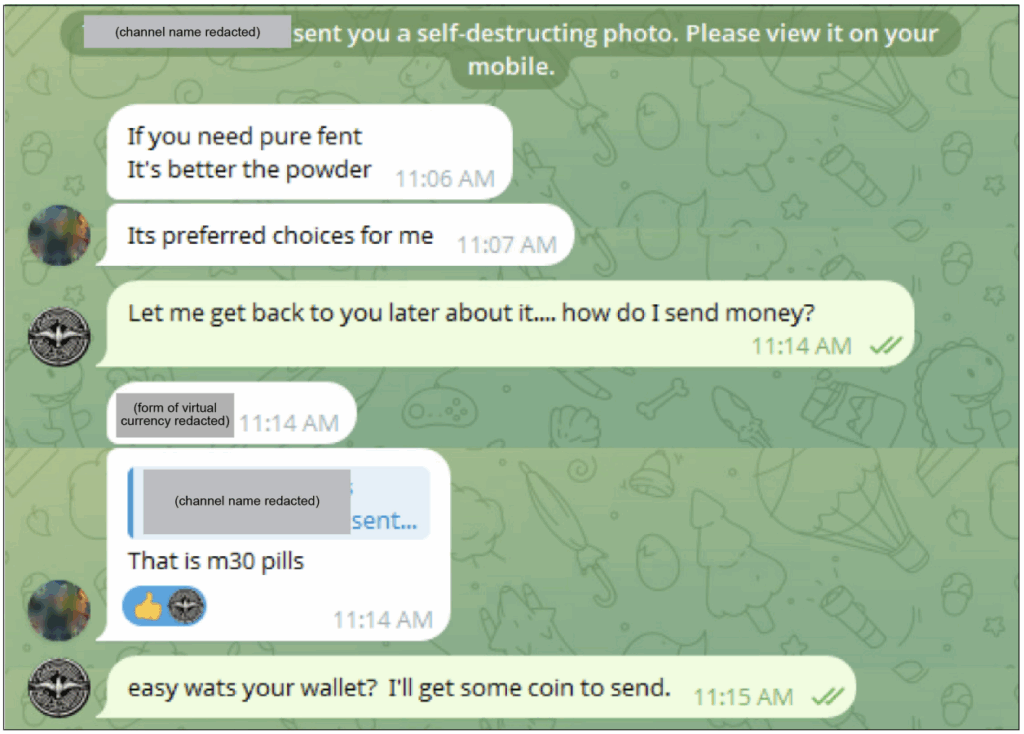

“We used undercover identities to communicate with purported drug suppliers about preferred communication platforms, pricing, and forms of payment,” the report states. “Our investigative work, however, did not confirm that the purported suppliers in fact sold the listed drugs.”

GAO also went undercover to communicate with “questionable” chemical companies, and also did not confirm that they sold the listed chemicals.

“[I]n our undercover work we communicated with a purported drug trafficker we found through a social media site, who then directed us to a channel on an encrypted messaging app,” the report states. “Our investigative work also identified purported sellers on online marketplaces who requested virtual currency as payment for synthetic drugs.”

They plan to refer both instances to the DEA “for follow-up as appropriate.”

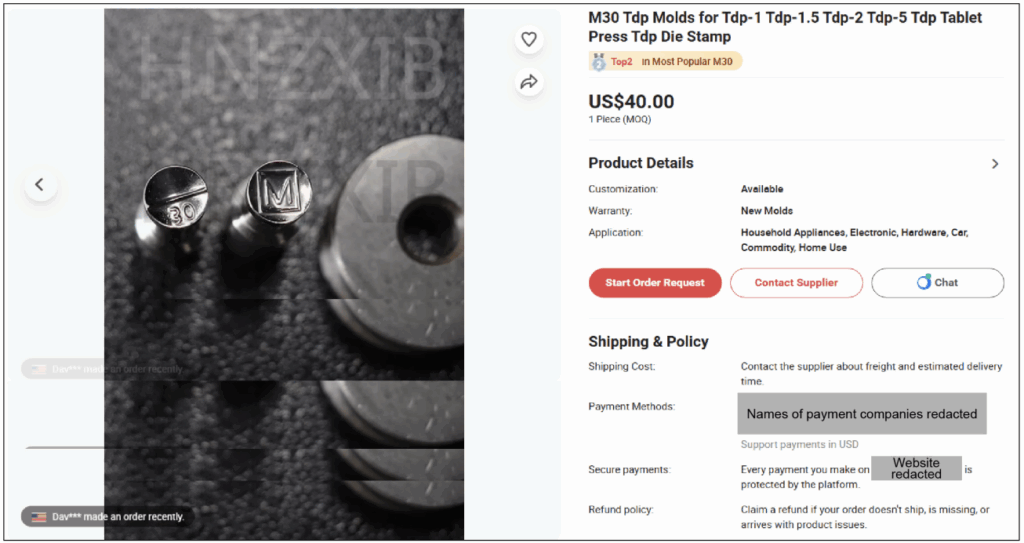

GAO’s investigative work also led it to “a die mold for producing counterfeit oxycodone ‘M30’ pills listed for sale online from a China-based company.”

“To illustrate how precursor chemicals and die molds are advertised and sold online for illicit drug manufacturing, we conducted surface web searches and used undercover identities to communicate with questionable China-based chemical companies,” the authors continued. “We identified companies as China-based by reviewing their stated location … product listings or ecommerce platform, but we did not independently verify their location.”

GAO, a nonpartisan federal agency that audits congressional spending, has from time to time gone undercover in the course of its duties, but the closest example appears to be a 2018 report focused on intellectual property and counterfeit trademarked goods. Its investigative findings in the December 18 report include that counterfeit tableting equipment appears to be sold online, and that people appear to use virtual currency to buy drugs online. The DEA has covered these activities pretty thoroughly, and the report authors seem mostly content to take the agency’s word for things.

Images (cropped) via Government Accountability Office