The 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment (NDTA) is such a widely cited document partly because it houses Drug Enforcement Administration info in one place, but mostly because the annual report hasn’t been published for the past three years. On May 9 the DEA released the 2024 NDTA, which mainly appears to be a vehicle for its synthetic drug propaganda. In its bid to separate fentanyl and methamphetamine from non-synthetics, however, the agency has made interesting choices in how it characterizes cocaine.

In what appears to be the DEA’s first use of the term in this context, the 2024 NDTA refers to heroin and cocaine as “traditional plant-based drugs”—which they are, it’s just a softer treatment than the agency has been known to give them historically. Previous NDTA have referred to morphine and cocaine as ”extracted from plant sources.” It’s a minor change, but notable in light of how the DEA is portraying cocaine-involved deaths, and because it’s slightly funny that the agency’s determination to make meth the scarier stimulant has evolved its cocaine rhetoric to include language previously reserved for psilocybin mushrooms and ayahuasca.

The 2024 edition includes data from 2021 and 2022, and somewhat awkwardly also includes partial data from the first half of 2023 even though the remainder wasn’t yet available.

Despite serving as several annual reports rolled into one, the 2024 edition is the leanest one since the DEA inherited the NDTA over a decade ago, following the closure of the National Drug Intelligence Center. It’s a little over half the size of the 2020 report and about one-third the size of all the other reports since 2015, when the agency started making them more of a production.

The 2024 NDTA is mainly concerned with transnational drug trafficking organization operations. All the drug-specific sections are a bit pared down, but even so you could almost miss the cocaine section—it’s barely over one page, with none of the customary charts or graphics included for all the other drug-specific sections, with the exception of New Psychoactive Substances.

In April 2023, the Biden administration launched a crackdown on illicit supply chains focused mainly on fentanyl, but on other synthetic drugs as well. As a synthetically produced drug meth is regularly pulled it in or out of that conversation as needed; cocaine is produced from coca plants, which is less convenient.

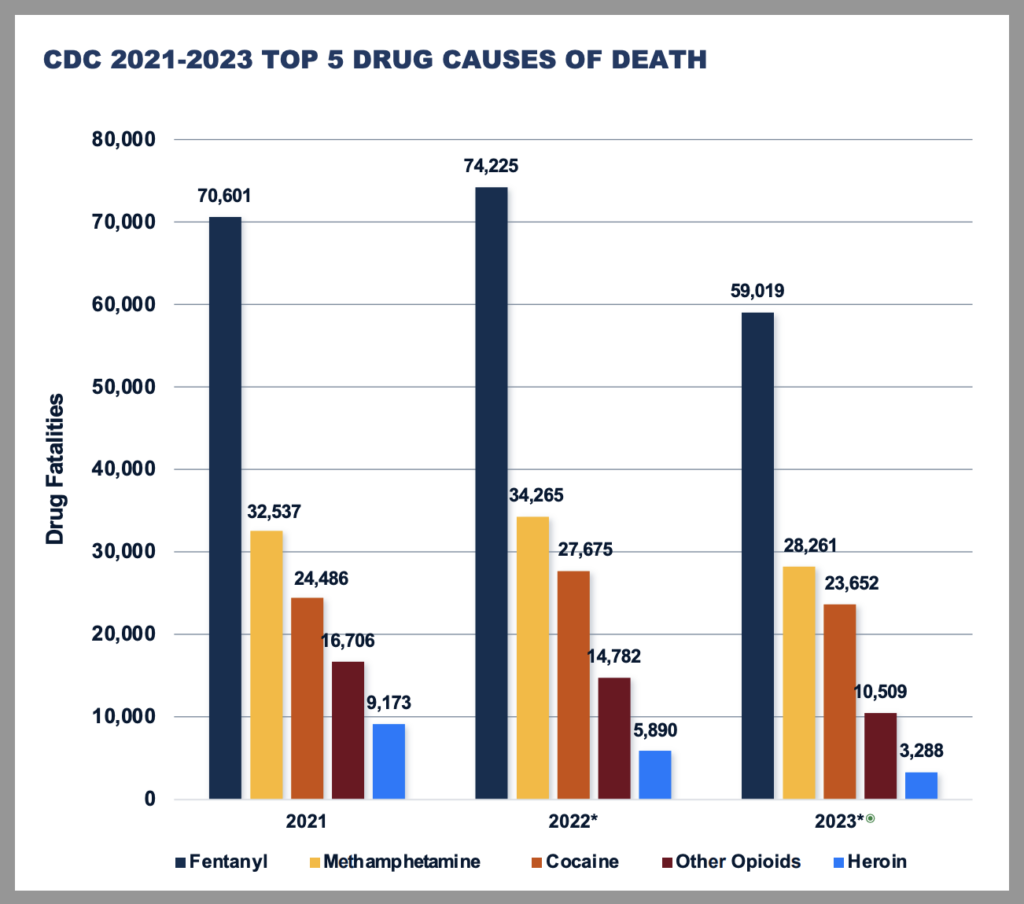

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention mortality data show the rate of meth-involved overdose deaths as moderately higher than the rate for cocaine-involved deaths. Broadly speaking, however, both have increased year after year and a majority of both also involve fentanyl. A little under one-quarter of cocaine-involved deaths are attributed to cocaine without the presence of fentanyl; for meth-involved deaths, it’s little under one-third.

“In some parts of the United States, at least two-thirds of the cocaine-related deaths also include findings of fatal levels of an opioid—usually fentanyl,” the report states. “Overdoses are rising as the amount of cocaine seized is falling because most of the fatalities cannot be blamed on the use of cocaine alone.”

Here’s the same CDC data being used to blame meth-involved fatalities on meth alone:

“Thirty-one percent of the drug-related deaths in the United States are caused by psychostimulants—mostly methamphetamine. In the first six months of 2023, more than 17,000 Americans died from overdoses and poisonings related to psychostimulants according to preliminary CDC figures—on track to exceed a record-high 34,265 fatalities in 2022.”

Cocaine-related fatalities in 2023 are also on track to exceed a record-high from 2022, according to the same preliminary CDC figures—29,918 up from 27,921. Seeing as the annual report was more than three years late already, the DEA might have waited a few more days so it could include the preliminary data for all 12 months of 2023, which was released May 15. The CDC has already recorded a confirmed 34,962 meth-involved deaths for 2023.

The section covering meth doesn’t mention fentanyl at all until the very last paragraph: “The number of methamphetamine-related drug overdoses in which fentanyl was also a factor is a growing concern. Both methamphetamine and fentanyl are dangerous and potentially deadly on their own,” the report stated. “Drug traffickers lacing methamphetamine with fentanyl is less common than the practice of lacing cocaine with fentanyl, but the combination presents the same risk.”

At the trafficking level, it’s not common that fentanyl is cut into either of them. Compared to meth-involved deaths, a higher proportion of cocaine-involved deaths do involve fentanyl. There are various reasons for this—starting with the fact that it’s easier for powder to mix with another powder than with crystals, whether intentionally or by accident—but all of them happen closer to the user-end of the drug supply chain.

There still appears to be no evidence that fentanyl has been found in counterfeit Adderall tablets, i.e. meth-pressed pills. In the 2020 report, however, meth pills were characterized as a “niche market.” The 2024 report states that such pills are “no longer a novelty, but an established and accepted form of the drug.” It goes on to incorrectly describe Ritalin and Concerta as amphetamine-type medications; both are brand names for methylphenidate, which is different stimulant.

Top photograph (cropped) of meth lab decontamination and inset graphic from 2024 National Drug Threat Assessment both via United States Drug Enforcement Administration

Show Comments