It seems today that everyone and their brother knows about the dopamine hypothesis of drug addiction. The popular version, simply put, holds that drugs cause pleasure by releasing dopamine into the brain’s reward center, and that addiction occurs when these drugs “hijack” our normal pleasure-seeking activities by releasing huge amounts of dopamine, inevitably turning us into monsters who live only for dope.

The reward center of the brain (the ventral striatum, which includes the nucleus accumbens) was discovered in 1954 by James Olds and Peter Milner. They implanted electrodes into the reward center of rats’ brains, connecting them to levers which the rats could press. Olds and Milner found that rats would spend all their time pressing the lever to stimulate the brain’s reward center to the exclusion of all else, including food and sex.

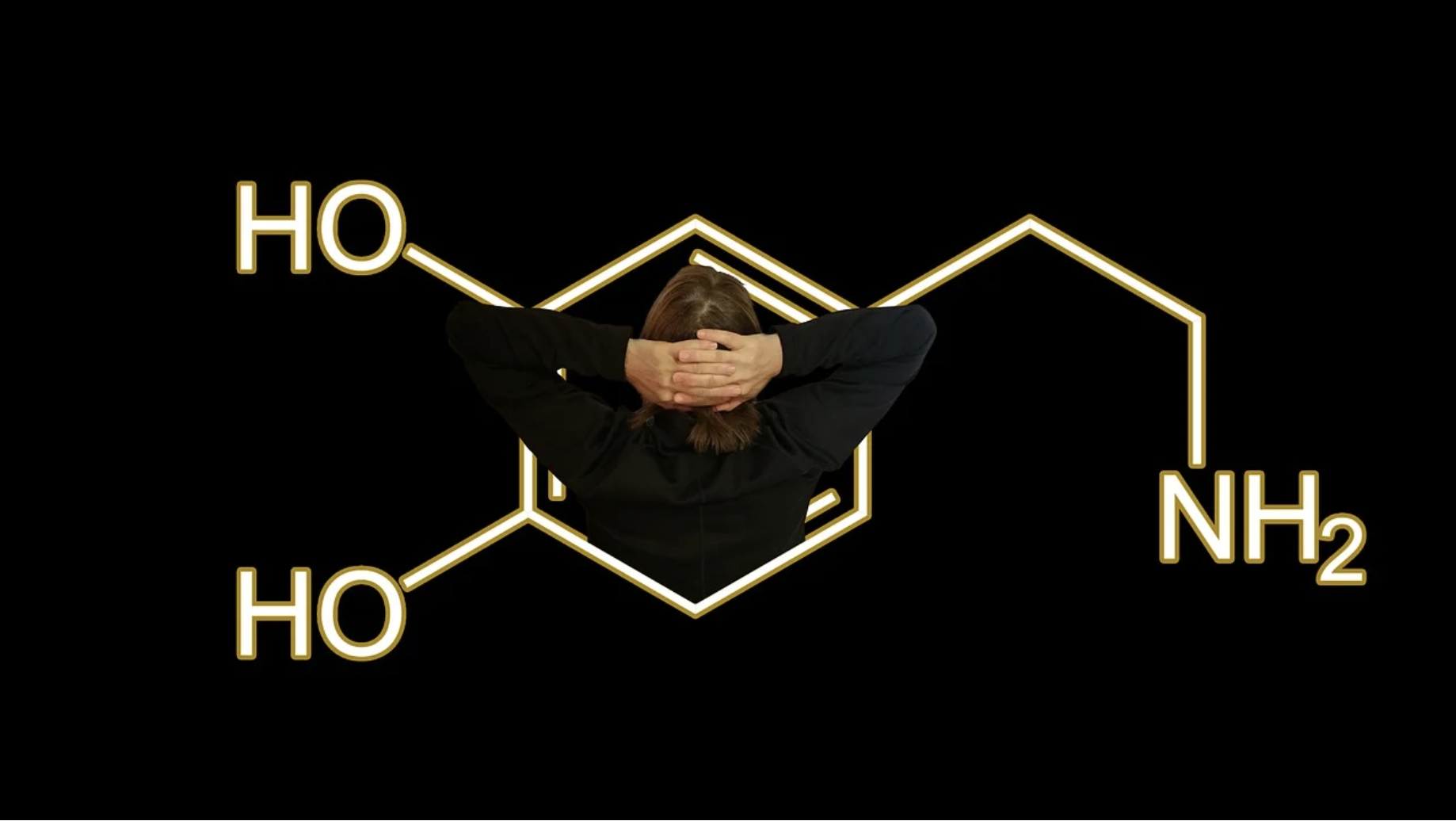

The dopamine hypothesis of drug addiction was first put forth in 1987, by Roy A. Wise and Michael A. Bozarth, and early versions framed dopamine as the “pleasure chemical” stimulating the “pleasure center” of the brain.

Dopamine is constantly being released into the brain’s reward center, whether one uses drugs or not. But the dopamine hypothesis defined drug addiction as the brain’s association of drug use with pleasure through large releases of dopamine.

The dopamine hypothesis, it should be noted, conveniently reinforces the capitalist-puritan notion that work is good and pleasure bad.

The hypothesis entered the popular consciousness with the publication of a 1997 story in Time magazine titled “Addicted: Why Do People Get Hooked?” Touting dopamine as the “pleasure chemical,” the article stated that all addictions—from drugs to drinking to smoking, but also non-drug activities like sex—were caused by its release into the brain’s “pleasure center.”

The dopamine hypothesis, it should be noted, conveniently reinforces the capitalist-puritan notion that work is good and pleasure bad, and that our purpose is to work to make profits for the billionaire class. We even have our modern picture of drug-hell, exemplified by the cocaine rat—which takes drugs until it dies, showing that the wages of pleasure are death.

But research by Kent C. Berridge in 2007 showed that dopamine was not a pleasure chemical at all. Dopamine is a reward chemical which causes people to “want” things, rather than a pleasure chemical which causes people to “like” things.

That, of course, doesn’t refute the dopamine hypothesis altogether. It does, though, raise the interesting question of what pleasure looks like in chemical terms. Scientific literature demonstrates no specific pleasure chemical, and researchers have identified a number of separate pleasure centers in the brain, known as “hedonic hotspots.” I would speculate that what we know as “pleasure” lumps together several components of the experience that do have separate chemical signifiers: relaxation (GABA), absence of pain (endorphins), love (oxytocin), stimulation (norepinephrine) and desire (dopamine), among others.

There are holes in the dopamine hypothesis big enough to throw an armadillo through.

Addiction researchers quickly fell in love with the unified theory of addiction given by the dopamine hypothesis. Drug warriors added it to their weaponry in claiming that drugs, not social or psychological conditions, were the problem. And profiteering rehab centers used it as one more marketing tool to get their hands on your bank account.

But, as David J. Nutt pointed out in a 2015 article, there are holes in the dopamine hypothesis big enough to throw an armadillo through.

There is strong evidence that stimulants such as amphetamine produce a release of dopamine in the reward center of humans compared to a control group (Drevets et al., 2001; Oswald et al., 2005; Martinez et al., 2007; Wand et al., 2007; Schneier et al., 2009; Leyton et al., 2002; Boileau et al., 2007; Narendran et al., 2010; Shotbolt et al., 2011), and fairly good evidence that alcohol produces such a release in humans (Boileau et al., 2003; Yoder et al., 2007). But there is little to no evidence that the same is true for opioids, cannabis, ketamine or nicotine.

Of two studies of heroin use in humans (Daglish et al., 2008; Watson et al., 2013), neither found any significant release of dopamine in the reward center compared to a control group.

Ritalin is a stimulant which is similar to, but milder than, amphetamine. It is far less associated with addiction than heroin, yet Ritalin, in contrast, produces a large release of dopamine in the reward center (Volkow et al., 1999). Modafinil, another stimulant deemed to have low potential for addiction, also causes a large dopamine release (Volkow et al., 2009).

Of two studies of THC use in humans, one (Stokes et al., 2009) found no significant release of dopamine in the reward center compared to a control group, whereas the other (Bossong et al., 2009) found a small but significant release.

Of three studies of ketamine in humans, two (Kegeles et al., 2002; Aalto et al., 2002) found no significant release of dopamine in the reward center compared to a control group, whereas one (Vollenweider et al., 2000) found a large and significant release.

Of six studies of nicotine in humans, two (Barrett et al., 2004; Montgomery et al., 2007) found no significant release of dopamine in the reward center compared to a control group, whereas four (Brody et al., 2004; Brody et al., 2006; Brody et al., 2009; Takahashi et al., 2008) found a significant release.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has continued to promote the dopamine hypothesis.

Moreover, different people have different quantities of dopamine receptors in their brains’ reward centers. If the dopamine hypothesis were correct, one would expect that people with many such receptors would be more vulnerable to addiction than those with few. Yet there is research that indicates the opposite. Volkow (2006) found that having many dopamine receptors in the reward center was protective against developing alcohol addiction.

Despite this, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), which is led by the author of that paper, Dr. Nora Volkow, has continued to promote the dopamine hypothesis.

In 2020, it put out an anti-drug propaganda pamphlet titled Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction. On page 17, the pamphlet states correctly that dopamine is responsible for reinforcement, not pleasure. However, on page 18, it contradicts itself by calling the dopamine reward center the “pleasure center” and saying that addictive drugs target this pleasure center.

Despite strong indications that dopamine plays no significant role in many addictions, the pamphlet states:

“Just as drugs produce intense euphoria, they also produce much larger surges of dopamine, powerfully reinforcing the connection between consumption of the drug, the resulting pleasure, and all the external cues linked to the experience. Large surges of dopamine ‘teach’ the brain to seek drugs at the expense of other, healthier goals and activities.”

Dopamine is found all over the brain, not just in the reward center. The chemical is essential for working memory, executive function, motor function, and many other functions. Excessive dopamine may be responsible for some psychosis.

As we have seen, dopamine in the reward system may be involved in the genesis of some addictions. But for others, there just isn’t the evidence to show that. And one thing dopamine is definitely not is “the pleasure chemical.”

Human brains and experiences are a heck of a lot more complex than the fried eggs of anti-drug PSAs. And people experience addictions to all kinds of activities other than drug use. It’s obvious why propagandists and marketers like the dopamine hypothesis, and equally clear that we shouldn’t buy their claims.

Image of dopamine formula via Pixabay

Show Comments