About a decade ago, people serving life with parole in Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) prisons began to realize we were just serving life. Each year a few dozen parole-eligible lifers are granted mercy, and a few thousand are left to rot with no reason ever given to them. A bill currently being read in the Georgia Senate would ask something unprecedented of the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles: transparency.

SB 586 appears to apply to anyone with a parole-eligible sentence who has earned the maximum possible performance incentive credits, or to lifers (who are not permitted to earn such credits) when we’re up for review. It proposes a few notable avenues of relief.

First, we could request a video conference hearing with the all five members of the Board, ahead of any decision on our case. Second, when parole is denied or delayed, we could request a written explanation of why. And third, in cases where the first three votes cast are all “No,” the remaining two members would be notified so that all may discuss and the early votes potentially withdrawn and reconsidered.

Since the bill’s introduction to the Senate on March 20, word has spread like wildfire through the medium-security facility where I’m currently housed. In the 30-plus years I’ve been incarcerated—and there are nearly 1,000 of us who have now been in GDC facilities that long—this is a first.

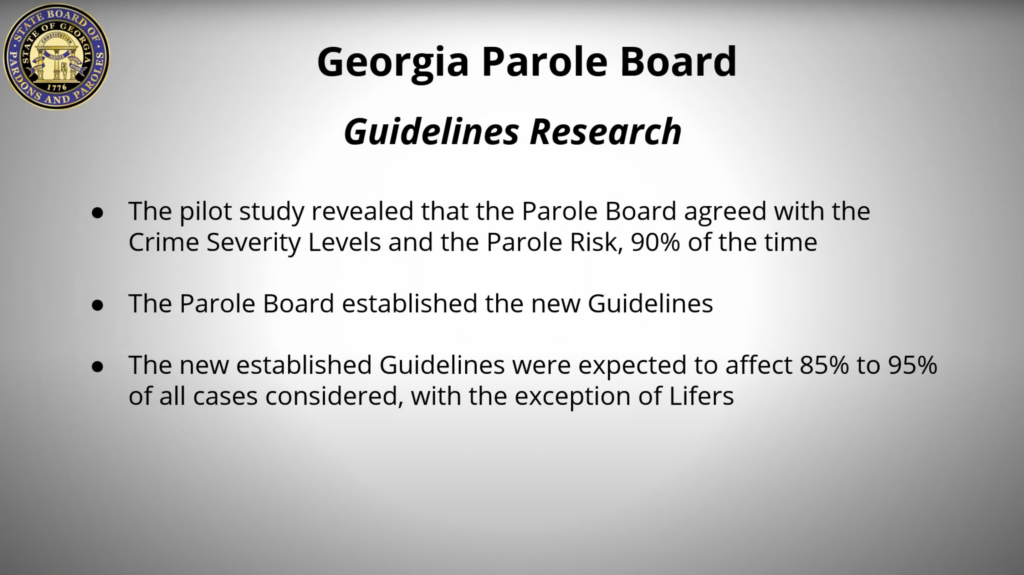

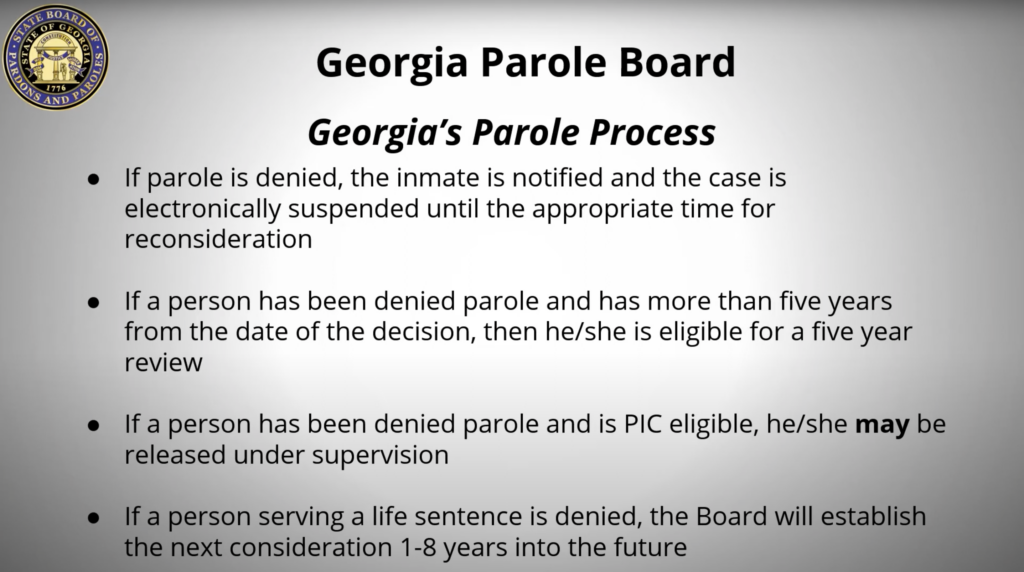

The Board never has to see or speak to us at all, let alone explain why we can’t go home, but it does at least have guidelines it’s supposed follow when reviewing parole-eligible cases. However, they don’t apply to lifers. The only right that we have is that our file be reviewed “at least once every eight years.” In 2023, the Board granted parole to 110 eligible lifers, and denied it to 2,254.

Currently, the way parole review works is that GDC uploads our files to the Georgia Parole Evidence-based Data System, for the Board members to review and vote on electronically. When a three-vote majority is reached, a notification is generated for the warden. It feels as automated as it sounds.

You can do a video interview with a parole officer where you have the opportunity to make a statement you want the Board to hear. The opportunity is widely understood to be merely window dressing; a pretty curtain behind which lies more concrete wall.

During the video conference outlined in SB 586, prisoners would have “a reasonable opportunity to present information” typical of clemency considerations. This includes information about our initial conviction and sentencing; our record of behavior while incarcerated; the level of outside support we have from family and other ties to community; the impact of release on victims and their families; and the sentiments of the local prosecuting attorney.

The written explanation for the decision would describe the “findings of fact, including the queries [from the interview], that provide the basis for the board’s decision.” It would also include names of anyone contacted on behalf of either the petitioner or victims, and whether that contact was made by phone, email or in person.

If this becomes law, everyone eligible for the video conference is going to request it. Everyone. Some may hope that looking at a human face rather an electronic file might stir up a bit more empathy; some may simply want to be looked in the eye when they’re told to try again in eight years. But all of us have questions only the Board can answer.

We’ll all request the explanations of denials, too. But among prisoners reached by Filter, the provision of most interest is this:

In any case where three members of the board have tentatively decided to deny parole or delay the tentative parole month, the other two members shall be notified of the tentative decision and given 14 days to hold the decision before it is issued. During such time such two members may discuss the decision with the other members of the board, and the majority who tentatively decided to deny parole or delay the tentative parole month shall, within their discretion, have the opportunity to change their vote.

That would take the blank cartridge from the proverbial rifle, rather than leaving their votes comfortably shrouded in secrecy. Everyone has the common sense to know that the probability of the General Assembly passing SB 586, and Governor Brian Kemp (R) signing it, and the Board adhering to it, is close to zero. But it’s notable that the Board is facing pressure for any transparency at all, especially when it doesn’t leave behind the lifers who are currently sitting in prison and don’t have to be.

It’s also possible that, thanks to SB 586, at some point in the next eight years we’ll each get the chance to present our case to the Board, and the Board will allow us to go home. Which is the worst part of something like this being dangled before us, even though we know it sounds too good to be true. All of us still want to believe.

Images via Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles

Show Comments