Bristol, the English city that produced street artist Banksy, will soon see the opening of the world’s first psychedelic-assisted therapy clinic of its kind. (Although Oregon will soon catch up, after passing a major psilocybin reform this month.)

The people behind this transformation in mental healthcare—a company called AWAKN Life Sciences Inc, led by scientists and drug policy reform advocates including Professor David Nutt and Dr. Ben Sessa—say that combining psychedelics with psychotherapy is the next evolution in psychiatry, and want to bring it to the masses. And with a staggering increase in mental health issues among people struggling with the conditions of the pandemic, the need for advances in this field couldn’t be starker.

“Now is the time for innovative approaches.”

“We are about to experience a massive wave of mental health problems—I’m seeing a rise in cases already in my caseload,” said Dr. Sessa, whose groundbreaking study of MDMA treatment for alcohol use disorder (AUD) Filter previously covered. “Now is the time for the innovative approaches to transform how we do psychiatry.”

Dr. Ben Sessa

AWAKN’s operation consists of three divisions, respectively focused on research (team members have also been involved in studies of ketamine for AUD and psilocybin for nicotine dependence); the development of clinics to provide treatment for issues including anxiety, depression and eating disorders as well as addiction; and training for clinicians interested in delivering such therapies. Given the list of experts and pioneers involved, the group looks set to become a global center of expertise in psychedelic-assisted therapy.

The initial treatment offered at a clinic in the Clifton neighborhood of Bristol, which is due to open in January 2021, will be ketamine-assisted psychotherapy, meaning a series of low doses of ketamine complemented by talk therapy sessions. The facility will include a dedicated autonomous research unit, three clinical rooms and space for patients to relax and recover from their treatment. AWAKN hopes to go on to open a chain of similar clinics in cities like London, Birmingham, Manchester and Brighton.

“We look forward to the day MDMA and psilocybin are fully approved as medicines … at present they can only be used as research trial drugs.”

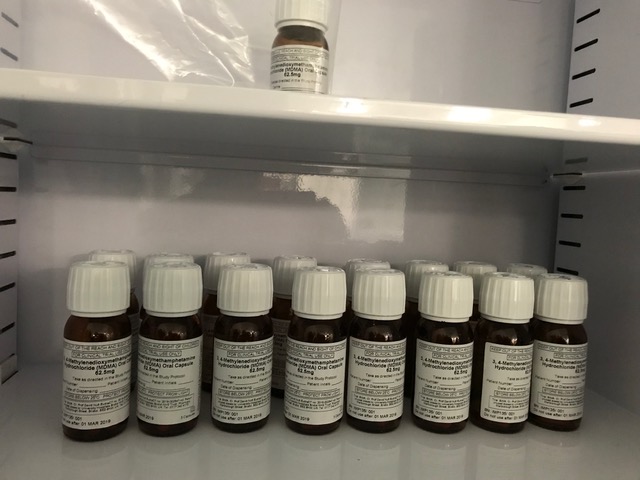

Ketamine has already been approved for medical use in the UK. Meanwhile AWAKN’s research division will continue to employ MDMA and psilocybin in clinical trials. “We look forward to the day these drugs are fully approved as medicines to be delivered to patients outside of research studies,” Sessa told Filter. “But at present they can only be used as research trial drugs. So we plan to also run from our clinic small research trials, which will mean we can be using MDMA and psilocybin in a research setting out of our building in Bristol.”

The MDMA cabinet

Despite its for-profit model, AWAKN’s ethos, say its founders, is to make this type of psychiatry available to all. Critically, however, its treatments have yet to be approved to be offered through the UK’s taxpayer-funded healthcare system, the NHS (National Health Service). So when the clinic opens, it will initially only be private, making it inaccessible to most.

“If we don’t win over the NHS, we are not going to be able to provide access to these services to everyone,” AWAKN CEO Anthony Tennyson told Filter. “it will just be a select few at the top, and personally I’m not interested in a select few at the top—they can take care of themselves!”

Dr. Sessa, a trained MDMA, ketamine and psilocybin therapist, echoed this dismay but is determined to press on. “I’m not waiting around another 10 years for the NHS to pull its finger out and decide whether or not it’s going to fund these safe, cost effective and vital treatments.”

Regarding AWAKN’s provision of clinician training courses for psychedelic-assisted therapy, Tennyson said it was an integral part of his belief that such compounds should benefit all of society, not just the few. Having only a handful of clinicians trained to offer psychedelic therapy for whenever new medications do get approved, he pointed out, will inherently restrict access.

“We need more people out there to deliver these services, so we’re teaching people to compete with us,” he said. “Business schools might say that’s not the right thing to do, but ethically, it is the right thing to do. We’ll be offering certified training under the authority of a regulated body—psychologists and psychiatrists, as opposed to shaman-type people with dream catchers. This is not to disparage anyone, but we’re looking to be the gold standard for medical and qualified practitioners to deliver these services, so it has to be people under the governance of the Royal College of Psychiatry.”

“This is a renaissance of psychiatry, not a renaissance of psychedelics.”

While the opening of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy clinics may seem like a radical departure, they previously existed in the UK, before being banned in the 1960s as a drug-war mentality took hold.

The new clinic takes shape

So what has changed in the last few years to enable this development? According to Prof. David Nutt, a renowned scientist who chairs both the nonprofit Drug Science and AWAKN’s scientific advisory board—and whose past role as a top government advisor ended after he repeatedly clashed with ministers, for example over his famous comparison of the risks of ecstasy to those of horse riding—it’s down to clinical trials.

Prof. Nutt told Filter of “the new neuroscience … that reveals specific brain effects compatible with therapeutic activity—and the increased number of small-scale clinical trials that reveal efficacy, and safety—so revealing that the government hysteria about the dangers of psychedelics that led to [clinics] being banned in the ‘60s was dishonest.”

Nutt, Sessa and many others see clinical research and affordable treatments and training in psychedelics as part of a bright new future for the mental health field. “This is a renaissance of psychiatry,” said Sessa, “not a renaissance of psychedelics.”

Photographs courtesy of AWAKN Life Sciences