Winning a prize for my laughable “dancing” skills at a bar in Havana was a major surprise. But it should have surprised me less that the gift bag I was awarded contained a box of cigarettes.

Tobacco is firmly entrenched in Cuban culture. The country is famous, of course, for its cigars, and its tobacco crop is one of its largest sources of income from foreign trade. Cuba’s smoking rate, as of 2015, was 37 percent. Although it’s gradually falling, it’s about three times higher than in the United States. Almost 20,000 Cubans die of smoking-related causes each year.

Cuba has experienced a tumultuous relationship with the US, which classifies the country as a “state sponsor of terrorism” alongside only North Korea, Iran and Syria. I was able to travel there on a family-visit visa. But as a Cuban American studying public health, I also wanted to learn more about how communities experience tobacco issues—and tobacco harm reduction, if at all.

I brought my vape along anyway, and was glad I did, because I saw no evidence of vapes on sale in brick-and-mortar stores after I arrived.

Although cigarettes and cigars are ubiquitous, Cuba’s laws around other nicotine products are not always easy to establish. According to the Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction, marketing of heated tobacco products or nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is illegal, while there is no available information about snus regulation and “no specific law” around vapes. Sources like the Canadian Government state that Cuban customs will seize vapes if you try to bring them into the country, while other sources say there’s no basis for these seizures under Cuban law. But vaping itself appears to be legal in the country, in the absence of regulation.

I brought my vape along anyway, and was glad I did, because I saw no evidence of vapes on sale in brick-and-mortar stores after I arrived. No one troubled me at the airport or when I vaped in Cuba.

I met Luis* through one of my family members a few days after I arrived. He was smoking cigarettes at a table in a bar in Havana, and I asked if he would be open to an interview about tobacco issues in Cuba.

Luis is Cuban and has lived there for most of his life. He’s smoked for most of his life, too, as have most of his friends. He started at 14. “Kids would just pick up cigarette butts to smoke them in a pipe,” he told me. “That’s how we started smoking.”

Almost 30 years later, he currently smokes two packs a day. “I think it’s stronger than any other addiction I’ve had,” he reflected. “Yes, stronger than drugs, alcohol, and all of that.”

He was pretty clear, too, that he didn’t want to smoke. “I’d like to stop smoking,” he said. The last time he tried, his method, as on previous occasions, was to go cold turkey. “In four days, I was smoking again.”

“I didn’t even know that existed until recently. You don’t see anyone vaping out here.”

Before we spoke, Luis had seen me vaping. He expressed interest in trying it—and did have some knowledge about it.

“Yes, I’d like it, so I don’t have to be anxious when I quit smoking,” he said. “It has nicotine … and it doesn’t harm as much as cigarettes that have millions of harmful chemicals.”

The obvious question, then, was why he wasn’t vaping already. “Well, that’s not available here,” he explained. “There’s no access. You can’t easily reach that. It’s expensive here.”

“I didn’t even know that existed until recently,” he continued. “You don’t see anyone vaping out here.”

That matched my own brief experience of the country—though I later discovered that a small number of people do vape in Cuba, purchasing supplies online. Nobody? I asked.

“Never in Cuba,” he replied, though he had witnessed it when he once spent time in Spain. “I don’t have friends that use it.”

We chatted more about the availability of different nicotine products in Cuba. Luis said that in his experience—and despite Cuba’s status as a major tobacco producer—there’s little-to-no access to forms of smokeless tobacco (like dip or snus) or even loose tobacco. It’s pretty much all cigarettes or cigars.

The government offers people free NRT, including gum, patches and nicotine drops.

However, despite the ban on marketing NRT, the government does offer people free NRT, including gum, patches and nicotine drops—as well as essential oils aimed at reducing nicotine-withdrawal symptoms like anxiety.

“Yes, the government supports those people,” Luis said. “You can go to a place in person, call on the phone, and it’s all free.” The actual gums or patches, in his experience, are scarce. “It’s mostly therapy, they talk to you with a psychologist for example.” (This was contrary to what I would later hear from other Cubans, who said they faced few barriers in accessing NRT products through government smoking cessation programs.)

Some people do find NRT effective for smoking cessation, though the best available evidence shows that vapes, which replicate the hand-to-mouth movements and inhalation of smoking, are more effective for this purpose.

Luis himself had the chance to try NRT while he was in Spain but, “my feeling to smoke didn’t go away.”

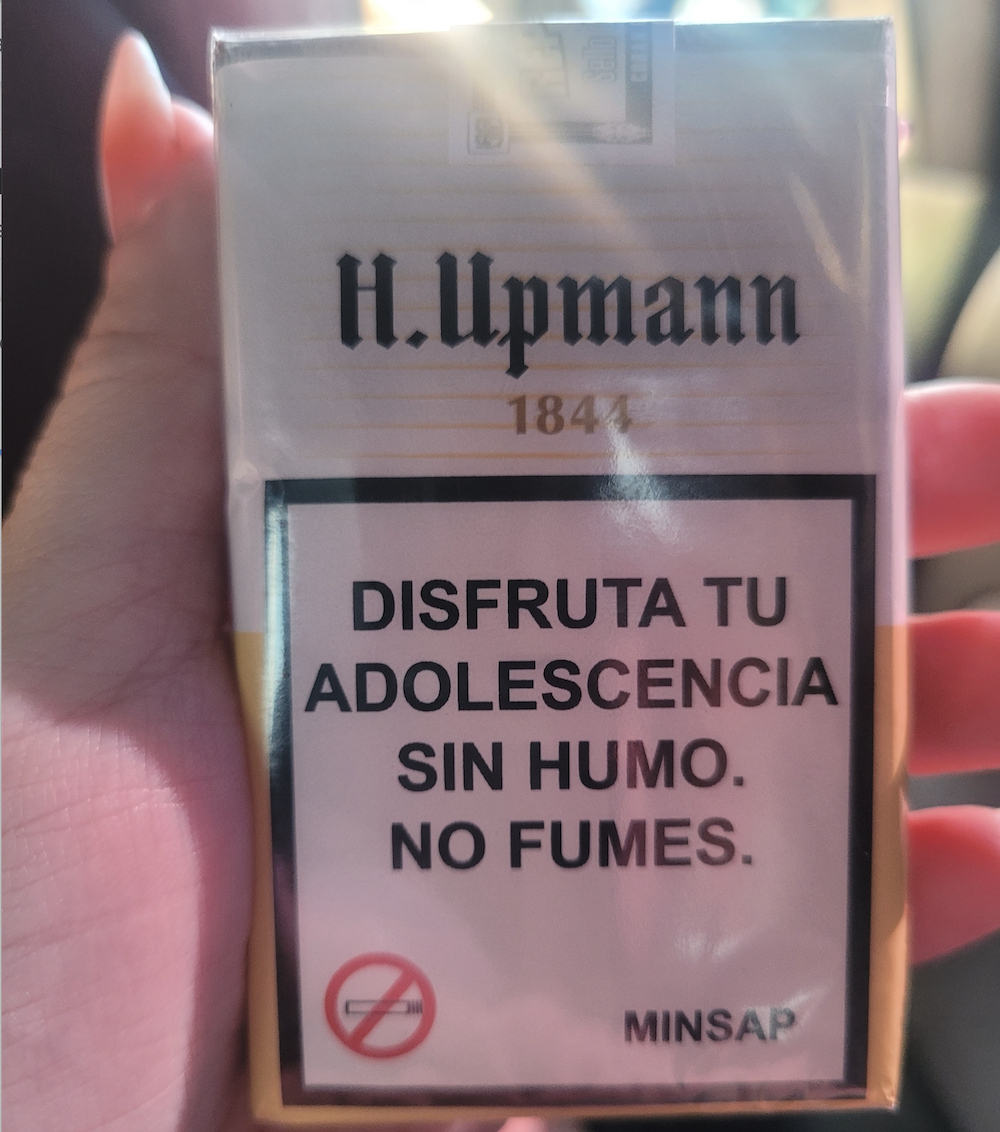

Cigarette packs in Cuba display health warnings, much like in other parts of the world. I asked Luis what he thought of these. “It’s something,” he said. “I think a lot of people look at this, especially those who are smoking every day, and say, damn. Maybe for some people it helps but for me it doesn’t help, I still smoke, my friends still smoke. But at least they tell you.”

Returning to something he’d said earlier, I mentioned that I wouldn’t have expected loose tobacco to be unavailable in Cuba, of all places. “Well, there’s sometimes even times of crisis where you can’t get cigarettes,” he responded. “Sometimes there aren’t any.”

I wondered if this reflected tobacco producers prioritizing the more lucrative export market over domestic availability. I asked whether people could still get cigars in those times.

“The people who can smoke all they want are privileged. Most people can’t afford to smoke too much.”

“Oh yeah—I can show you, look.”

Luis then produced several that he had on him. “These cigars right here are bad quality. The worst that there is. The small ones suck, they go for around 1 Cuban peso. They’re for the public, they are sold cheap.”

On the other hand, “The nice big one is made by particulares [a kind of private business]. It’s worth about 100 pesos.”

“When there’s no cigarettes, that’s usually when people smoke cigars,” he explained. “Sometimes people will gut it, and roll it using any paper they can find. That’s very common among people who don’t have funds. They sometimes use bibles to roll their tobacco. Sometimes people use pipes as well. In Cuba, even if you don’t have money you can also figure something out. Find someone who will gift you a cigarette, maybe.”

“The people who can smoke all they want are privileged,” he added. “Most people can’t afford to smoke too much.”

Luis gave more insight into just how central tobacco is to Cuban culture when he described an annual “tobacco day,” a kind of international fair.

I later confirmed it’s called the Habanos Festival. At this year’s event, Cohiba humidor was auctioned for a record $4.4 million. According to festival organizers, proceeds are donated to Cuban health authorities.

“They blindfold people and they are able to tell which tobacco or cigar is which.”

“The fair is huge. It’s a nice fair,” Luis said. “People go to smoke and have fun. Foreigners come to smoke their cigars there. Catadores, too.”

I didn’t know that word. “Those are tobacco experts that try the cigars and rate them. They do competitions of who’s the best catadore. The winner gets a prize.”

“The experts in tobacco know it by smell,” he continued. “In tobacco competitions, they blindfold people and they are able to tell which tobacco or cigar is which… The last winner I saw was a young woman. With her eyes blindfolded, smoked or smelled, she knows the size, type, everything. It’s crazy.”

I asked what the crowds are like at these events. “It’s mostly people from the government. Those who go are the ones working in Cuba tobacco control. They have the factories. You can go too, but it’s mostly government folks and foreigners who are the ones that buy tobacco.”

“But if I had to choose,” he asserted again, “I would vape. My phlegm is dark and thick.”

*Name changed to protect privacy at source’s request.

All photographs by Kevin Garcia

The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter, has received donations and grants from Knowledge-Action-Change, which publishes the Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction.