Tobacco use is a poor person’s problem. People with low incomes consume and grow it the most and suffer the gravest consequences from its trade and use. Yet tobacco control policies do not adequately address their needs, merely using them as statistics to highlight the enormity of problems rather than implementing measures to benefit them.

Globally, 84 percent of smokers now live in low- and middle-income countries, which are also where around 90 percent of tobacco farming takes place. Even in the West, smoking is more prevalent in economically disadvantaged communities. This worldwide class disparity is set to grow. While tobacco use is declining in the West, it continues to increase in LMICs, which are projected to suffer three times the wealthier world’s death toll by 2030.

The impact of tobacco use on the poor is more severe in health and financial terms. The costs of tobacco and associated healthcare strain family budgets and reduce spending in areas like children’s education, pushing smokers and their families further into poverty.

The most favoured tobacco control measure—tax increases—exacerbates the problem. Further stressing poor smokers’ limited resources, it often forces them to switch to cheaper, even more harmful alternatives—for example, the traditional bidis (unprocessed tobacco smoked in rolled leaves) that are far more popular than cigarettes in India.

India loses over 1.3 million lives annually.

Yet keeping taxes on tobacco products used by the poor low is not a better option. This is the case here in India, where almost 80 percent of tobacco tax revenue is from cigarettes—the country has the highest per capita cigarette tax in the world—while bidis are taxed at far lower rates. This incentivises and perpetuates the most harmful tobacco use—dissuading bidi smokers from moving down the harm spectrum by transitioning to cigarettes, while forcing many cigarettes users to pick up deadlier bidis.

The personal suffering of tobacco users who do not have the means nor access to medical care continues to be overlooked in policymaking. In India for instance, only 19 smoking cessation centres exist for a tobacco-using population of about 270 million, while there is no national policy to make telemedicine or other medical support available. Consequently, mortality and morbidity are high: The country loses over 1.3 million lives annually, tobacco-related cancers continue to rise, and rising economic costs drain public finances.

These shortfalls apply globally. Uganda is the only LMIC to have effective monitoring of tobacco use and around 30 percent of LMICs have no tobacco cessation programs, even as they foot the majority of the world’s $1.4 trillion annual costs from tobacco use.

The quit support that does exist is largely limited to services, mainly phone counseling, with questionable efficacy and little reach to poor communities. Further, nicotine gums and patches are unaffordable to most cigarette smokers in India—let alone bidi and khaini users—and there is no movement on subsidizing them, despite their being placed on the essential medicines list by the World Health Organization.

Why Is Tobacco Use Prevalent in Low-Income Populations?

Any attempt to honestly tackle this crisis ought to first factor in why poor populations use tobacco in such large numbers. The most cited reason is that they lack adequate information about the harms of tobacco use—but this is increasingly untrue for most parts of the world, as anti-tobacco efforts reach communities across the spectrum. The deeper, more insidious causes highlight the intricate role tobacco plays in such societies.

For people living in poverty, hunger is ubiquitous, and nicotine helps alleviate it for many. Just like the trope of fashion models smoking to stay thin, farm workers in rural India chew tobacco and construction labourers in cities smoke it to suppress appetite, helping them to work longer hours and spend less on food. Poverty also means stress, and nicotine’s calming effect can help there too, as high rates of nicotine use among people with mental health challenges attest.

In rural India, the absence of toilets in many homes means that villagers use tobacco for another practical purpose: to control bowel movements when they go to open areas to defecate. Tobacco-based toothpaste is commonly sold in India for this reason.

In some communities, tobacco is also embedded into cultural identity and rituals.

Other reasons highlighted in research are that many use nicotine as self-medication for ailments they falsely believe it will relieve. And the importance of pleasure in difficult lives should not be underestimated—people may perceive tobacco as a “reward,” one of the few enjoyable things that they can do for themselves. Poor people, struggling with immediate daily challenges, may also feel they have less to lose from future illness and may become more dependent given their dietary and social conditions.

In some communities, tobacco is also embedded into cultural identity and rituals. In the northeast of India, for instance, gifting tobacco during occasions is widespread practice. In villages where tobacco is cultivated, the crop is the focal point of the community. The farmer and his helpers grow and reap the plant, which is traditionally sorted and processed by women at home, while others transport it to markets—each specialization honed over generations. The deep integration of a crop into the social, cultural and economic fabric of farming societies makes simplistic crop-switching initiatives unsuccessful.

These factors run counter to the narrative that the tobacco habit is an extraneous force, demanding simplistic interventions aimed at propping up willpower-backed quit attempts—followed, when such interventions predictably fail, by pinning the blame on communities themselves with overarching terms such as “low desire to quit.”

Until the underlying causes of tobacco use—and the roles nicotine plays in people’s lives—are accepted, understood and addressed, efforts to reduce the tobacco health burden will continue to fail.

How Tobacco Harm Reduction Can Help

Efforts to combat malnutrition in India—comprising a holistic view of problems and contributing factors, evidence-led interventions, industry partnership and tailored efforts to modify behavior—created successful public health strategies. There is no reason why these approaches should not be adopted to tackle the tobacco crisis.

In this context, especially with high tobacco use, lack of motivating factors to quit and inadequate support, it is vital to consider harm reduction measures.

The onus to address the tobacco epidemic is currently largely on the Indian state. Its resources are stretched between enforcement of supply reduction measures, getting current users to quit and preventing uptake, as well as the somewhat contrasting imperatives of looking out for tobacco farmers and maintaining the state’s foothold in the trade though its investments in tobacco companies and tax revenues.

Tobacco harm reduction measures, if implemented with sensitivity, can help balance the equation.

Encouraging tobacco users to modify behavior, by making lower-risk alternatives available at lower cost, can bring down tobacco-related harms. Most people, regardless of socio-economic status, understand the risks associated with tobacco use and want to protect their health.

An example is the popularity of chaini khaini, a smokeless product falsely marketed in India as snus and carrying a higher risk profile. Many people have nonetheless switched to it in the belief that it is safer. If genuinely risk-reduced alternatives were accessible, affordable and perhaps incentivized, a rapid lowering of population-level harm would be achievable without drawing heavily on the state’s resources.

It is a widely held belief that harm reduction alternatives are expensive … This view overlooks the ingenuity of people in LMICs.

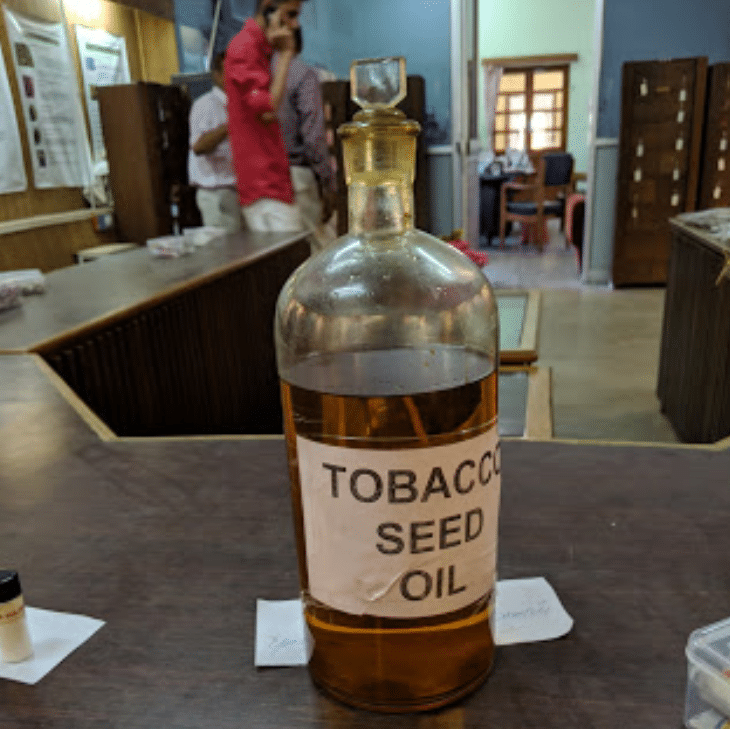

The harm reduction approach factors in the various integrations of tobacco and nicotine into people’s lives, instead of focusing entirely on severing these links. It is also sensitive to the situation of farmers, providing alternatives to preserve their livelihoods. One way to do this is to develop supply chains for the various other uses of tobacco, from making of cardiac drugs, oil to protein powder, which I learnt about while visiting the state-funded Central Tobacco Research Institute in southern India.

It is a widely held belief that harm reduction alternatives are expensive—that being technology- and research-intensive, it is difficult to make them available below certain price thresholds. This view overlooks the ingenuity of people in LMICs and how other tech resources—from mobile phones to patented medicines—have been adapted and widely adopted.

In a project to evaluate the efficacy and affordability of vaping for India’s bidi users, supported by Knowledge-Action-Change, I found positive outcomes for both, if adequate modifications are made. It turns out that even at current prices, vaping devices and appropriately flavoured e-liquids (India is a major producer of liquid nicotine) are within the reach of bidi smokers. Another project in the same vein found that lower-risk snus can be made locally at price points khaini users can afford. If state support though tax incentives is applied, these lifesaving options can be produced and distributed at scale.

The Road Ahead

Despite the urgent need, and the availability of solutions, India appears determined to shun the strategy of tobacco harm reduction. In late 2019 it banned vaping, and there are troubling signs of opposition developing to snus and nicotine pouches.

Just as the bidi/khaini vs cigarette taxation gap ends up incentivizing the former, banning lower-risk products perpetuates deadly forms of tobacco use and eliminates the health benefits and green economic opportunities that a harm reduction model would bring.

Under this model, the government’s control of the tobacco trade, which extends from providing seeds to farmers to partially owning tobacco companies, could even become a force for good because it could directly influence the shift away from deadly products. With even a light touch in the right direction, Indian entrepreneurship, celebrated the world over, could rapidly become engaged in indigenously developing culturally specific tobacco harm reduction solutions, helping improve public health and creating jobs in the process.

What we still lack is the political will to help some of the world’s most vulnerable smokers.

Photographs courtesy of Samrat Chowdhery

Knowledge-Action-Change has provided scholarships to The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter, to support tobacco harm reduction reporting. Both The Influence Foundation and INNCO have received grants from the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World.