If numbers gauge the health of a movement, this one is flourishing. Two thousand people crammed into a vast hotel ballroom in New Orleans on October 18 for the opening of the National Harm Reduction Conference—a record for the event and also, organizers reckon, for any harm reduction conference in the world.

Yet leaders painted a mixed picture—one of a movement blessed with extraordinary power, imagination and humanitarian values, but simultaneously assailed by external threats to its success and internal threats to its integrity.

“This year’s conference is different for a lot of reasons,” said Monique Tula, executive director of the Harm Reduction Coalition, which organizes this event every two years.

[Monique Tula. Credit: Harm Reduction International.]

The last conference was in San Diego in 2016. It ended two days before the election of Donald Trump struck a bitter blow.

“It was a really dark time,” said Tula. “In San Diego none of us thought we’d be in the place we are today …. where our rights and our well-being are being steadily eroded.” She referenced the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, new laws targeting sex workers, and racial injustice as cases in point.

She also spoke, in the context of a crisis of an estimated 72,000 drug-related fatalities last year and soaring suicide rates, of “deaths of despair—Americans reacting to stressors with desperation.” The Trump administration has worked to re-ignite the devastating War on Drugs, even as many state- and local level harm reduction initiatives have advanced.

“Harm Reduction with a capital ‘H’ and ‘R’—this is the movement, one that shifts resources and power to the people who are most vulnerable to structural violence.”

“This conference is an example of how we hold space for each other,” Tula declared, having identified as a person who uses drugs. And indeed, to those who have regularly attended this event, its strong, inclusive sense of family has always been apparent.

This inclusiveness is reflected in an open panel application process, resulting in myriad perspectives and areas of expertise among scores of panels, roundtables and workshops squeezed into four hyper-stimulated days. Session titles include: Safer Washrooms Save Lives; Kwe to Kwe—A Harm Reduction Support Group for Indigenous Women Who Use Drugs; Let’s Queer This Up: Housing Disparities for the LGBTQ Community; Negotiating Sex Work and Client Interactions in the Context of a Fentanyl Crisis; and Disrupting the Great White Hope: Harm Reduction of Color. But no snapshot can capture the dizzying range on offer.

Whether this apparent diversity and breadth of application is enough, however—whether it is more than window-dressing amid systemic harms stretching far beyond those related to drugs—is a question this movement has long asked itself.

Tula, the first woman of color to lead her organization, framed these tensions thoughtfully. “When we talk about harm reduction, we often reduce it to a public health framework, [one of] reducing risks,” she told the crowd. “That’s harm reduction with a small ‘h-r’. Harm reduction is meeting people where they are but not leaving them there.”

“But Harm Reduction with a capital ‘H’ and ‘R’—this is the movement, one that shifts resources and power to the people who are most vulnerable to structural violence.” She went on to describe its aims as including: building community for and empowering directly impacted people, or “people who are not seen;” disruption; changing narratives; solidarity; and fighting for social justice.

Quoting author and civil rights advocate Michelle Alexander’s recent New York Times op-ed, Tula evoked the “revolutionary river” of which harm reduction is part, and placed Donald Trump and those who support him—”for whatever fuckin’ reason they do”—as “those who are pushing back against this new country struggling to be born.” Not that the current political and social climate is as new as some portray it. As author and activist Adrienne Maree Brown put it: “Things are not getting worse, they’re getting uncovered.”

Later in the day, Tula stressed to Filter that she remains “extremely optimistic” about the movement’s long-term prospects. Wrongs being uncovered are better than their continuing to exist unseen. “Compared with the elite one or two percent, we are legion,” she said. “We are incredibly powerful, and that’s what this movement really is; it’s about the 99 percent. And [the political reactions] we’re seeing now is the elite pushing back—because they’re feeling threatened.”

Back in the ballroom, having addressed these external threats, Tula turned to some closer to home. She warned those present of the dangers of “losing faith” or “lashing out” at each other, as family members might, rather than focusing on the bigger picture. She noted that “for a movement that espouses non-judgement, sometimes we can be really judgemental. Forgiveness and compassion—isn’t that the core of harm reduction?”

She closed, however, with some challenging questions. “If harm reduction is going to remain relevant and deeply accountable to those most harmed, how do we talk about racial injustice within our movement? Or misogyny? Or ageism? Or the very real trend that people with lived experience are being de-centered by this movement?”

“It’s appalling to me to see the ways that Black folks and our experiences are devalued.”

The plenary panel that followed her speech expanded on these themes. Black leadership within the movement—and its suppression—was a central focus. (The establishment of the Black Harm Reduction Network, which held its inaugural meeting here on October 17, is one part of efforts toward change.)

Erica Woodland, director of National Queer and Trans Therapists of Color Network, spoke of quitting the harm reduction movement 12 years ago, without mincing his words about why. “It’s pretty appalling to me to see the ways that Black folks and our experiences are devalued,” he said. “I don’t want to leave here with more empty promises.”

That Tula persuaded him to appear could be taken as a hopeful sign. “I got divorced from y’all,” said Woodland. “I came back; we’re dating!”

Black women, and in particular panelist Deon Haywood, lead Women With a Vision, a New Orleans-based nonprofit that applies harm reduction principles to drug use and sex work, but also to wider areas of racial, social and reproductive justice.

Haywood echoed Tula’s demand that harm reduction be more than a set of public-health risk management strategies. “Harm reduction may have been founded in sex and drugs and related things,” she said. “But the future … is: We have to see harm reduction as broadly as it is, as wide open.”

Further discussion included issues like labor exploitation in the “non-profit-industrial complex,” where thousands of peer workers and volunteers do lifesaving work for little or no pay.

The panelists also expressed resentment at how harm reduction has been co-opted by the public health establishment in ways that limit and misapply its potential. Haywood recalled being invited by a local public health body to a meeting to address “our new public-health approach of harm reduction”—this, when she and her colleagues have been applying harm reduction in the area for almost 30 years, and were previously denied requested meetings with public health officials. She pithily summed up her feelings at the time: “Bitch…!”

Shira Hassan, an advocate for sex workers, University of Chicago lecturer, and former director of the Young Women’s Empowerment Project, added that harm reduction’s history has also been co-opted by public health. “Who was it started by? It was started by us, by drug users and sex workers, street-based people, trans people of color. Because we have been saving our own lives for centuries.”

In a call to “reclaim our reality,” she referenced her lived experience in noting that “intersectionality is a big word to describe the truth of our reality. It’s what it is to wake up queer and Arab every day, and be involved in the sex trade.”

Hassan described harm reduction as “this incredibly beautiful thing” in urging the movement to link better with others (“What is harm reduction without prison abolition, without transformative justice?”). She also emphasized her gratitude. “Someone handed me a clean syringe when I was sleeping under a bush in New York City … and you all saved my life … Thank you!”

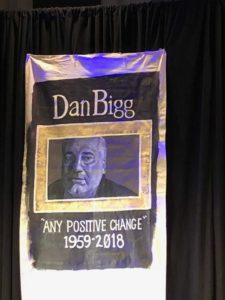

Dan Bigg provided naloxone and sterile syringes but also love and inspiration to many people who use drugs.

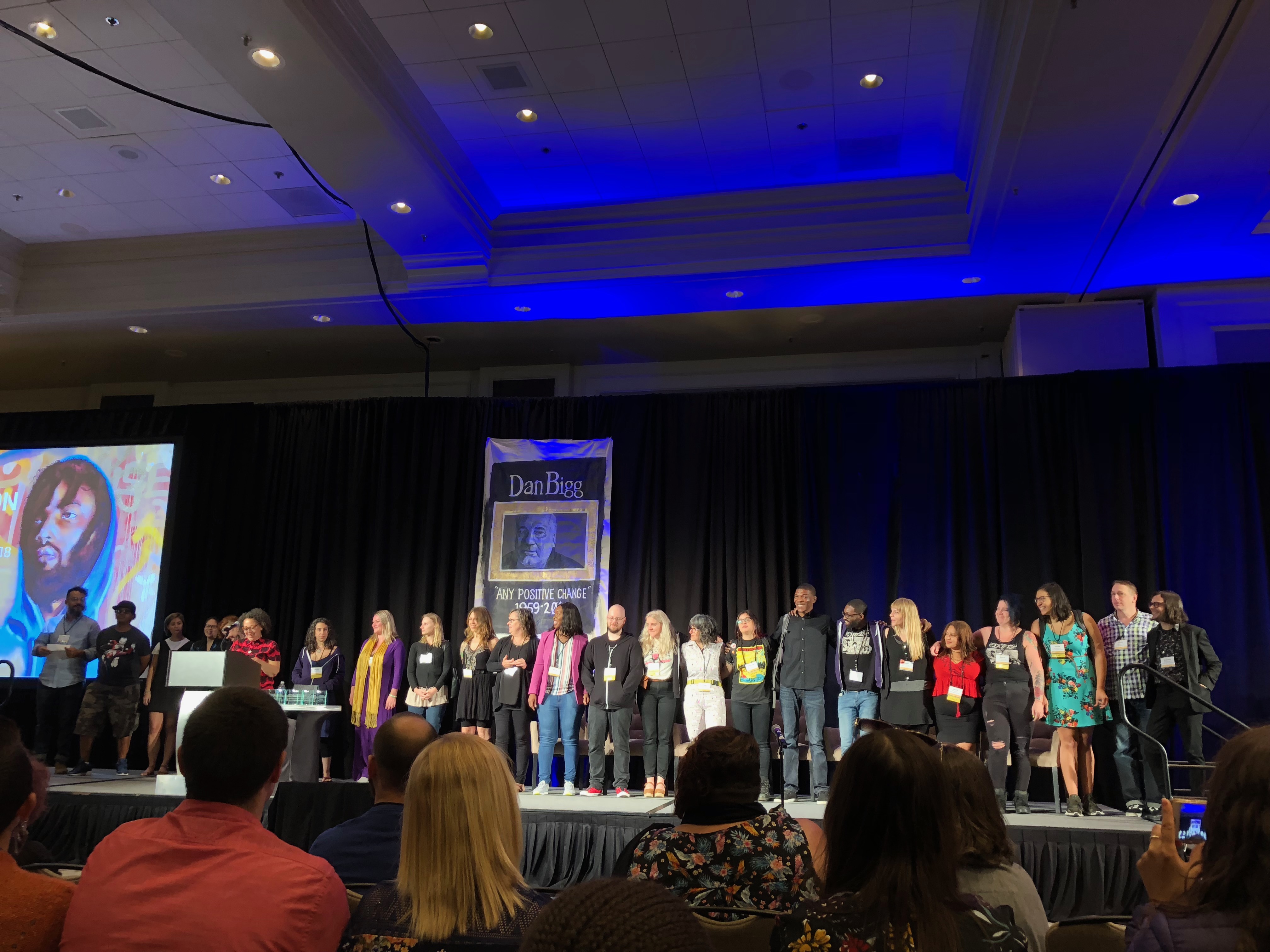

One giant figure behind this kind of lifesaving work was Dan Bigg. Described as the “godfather” of harm reduction, Bigg co-founded the Chicago Recovery Alliance and for decades provided naloxone and sterile syringes—whether the law allowed it or not—but also love and inspiration to many people who use drugs. He died in August. His presence—with his faced printed on a drape above the stage—loomed over this event.

“This year’s conference is different for a lot of reasons,” Monique Tula had said at the beginning of her speech. “But perhaps the most important is that for the first time, we’re having it without Dan.”

In tribute, his widow, Karen, and the staff of Chicago Recovery Alliance assembled on the stage. Several were in tears—not a rarity at a conference where so many lost lives are remembered. Bigg was lauded for his boldness, his “general badassery,” his compassion, and for “asking forgiveness rather than asking permission—taking risks to save lives.”

A regular award—the “Any Positive Change” award—has been established in his honor, and the inaugural winner was an equally inspiring figure: Louise Vincent. She is the national director of the Urban Survivors Union of drug users, runs a syringe exchange in Greensboro, North Carolina, and has been involved in saving hundreds of lives—again, whether or not laws permit the tools required to do so, and despite DEA raids.

Aspects of Vincent’s story exemplify the passion to fight for humanity which the harm reduction movement—for all its flaws and self-doubt—still embodies.

“It’s been harm reduction and this work that sustained me when my daughter died,” she told us. “It’s been harm reduction and this work that sustained me when my leg was gone. And it’s harm reduction and this work that keeps me alive and going forward every day.”

Photo credits (unless stated): Filter.

Show Comments