In Bangor, Maine, a familiar narrative is playing out: Local officials perpetuating complaints of “syringe litter” in public spaces, while safe disposal bins go underfunded and encampment sweeps leave many people who use drugs with no private spaces to do so.

“I don’t want to stop people from getting the needles they need to use drugs safely,” City Councilor Cara Pelletier told Bangor Daily News. “I also don’t want the other thousands of people in Bangor to be stepping on needles, finding needles in lakes and streams and being afraid to go use playground equipment.”

Maine made syringes an over-the-counter product, rather than a prescription-only one, in 1993. And it authorized syringe service programs (SSP) in 1997. But in doing so, it restricted SSP to only giving someone sterile syringes if they first brought in an equal number of used ones, a policy known as 1:1. Evidence is clear that giving people as many syringes as they need best protects public health by preventing disease transmission and other harms.

In March 2020, Governor Janet Mills (D) issued an executive order temporarily suspending 1:1, as part of the state’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. That order expired in August 2021. But in November 2022, the state finally ended 1:1, replacing it with an expanded rule authorizing SSP to give participants up to 100 syringes per visit.

Returning used syringes is no longer required to receive sterile ones, but there’s no evidence that this is linked to more syringes being publicly discarded. Meanwhile, Bangor hasn’t provided adequate syringe disposal resources.

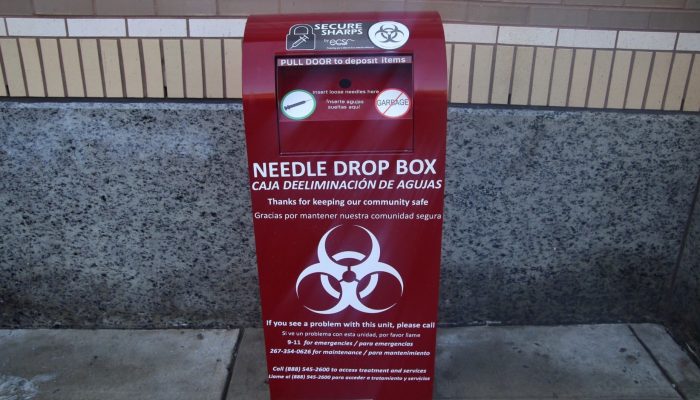

Whitney Parrish Perry, director of operations at Maine Access Points in Bangor, told Filter that even though city officials have installed a few sharps disposal bins around town, they’re much too small and aren’t emptied regularly.

“Often they were overflowing,” she said, “and we would get reports that people were reusing syringes.”

“We are a resource to people in the community to have syringes disposed in the proper manner.”

SSP workers take up the slack. Outreach walkabouts where peers and other harm reduction workers conduct regular cleanups mean that SSP are consistently associated with neighborhoods seeing fewer discarded syringes, not more.

“We are a resource to people in the community to have syringes disposed in the proper manner,” Jill Henderson, communications and development manager at local SSP Bangor Health Equity Alliance (HEAL), told Filter. “Including supporting maintenance and emptying of sharps boxes and sending our folks out to do outreach to affected areas.”

In 2021, HEAL submitted an application to local officials to implement a program called SharpSmart, with technology allowing people who find publicly discarded syringes to snap a photo or otherwise report the location to HEAL so they can send someone to take care of it.

The best way to ensure used syringes are removed from public spaces is to fund SSP. The best way to prevent syringes from being used and discarded in public spaces in the first place is to increase access to housing.

“Bangor has been experiencing a housing crisis for a very long time,” Parrish Perry said. “The city, with support of the police, have engaged multiple sweeps on communities of unhoused people.”

“If there is an uptick of syringe litter seen by the city,” she continued, “the city should consider the impacts of having a disposal facility that allegedly cannot process syringes … and practices like encampment sweeps that severely disrupt the lives of people trying to build community and safety in the absence of support from the municipality.”

Photograph via City of Philadelphia