State prisons’ efforts to decarcerate during the COVID-19 crisis seem to have been eclipsed by those of county jails—despite more than half of all incarcerated people being housed in state-run facilities.

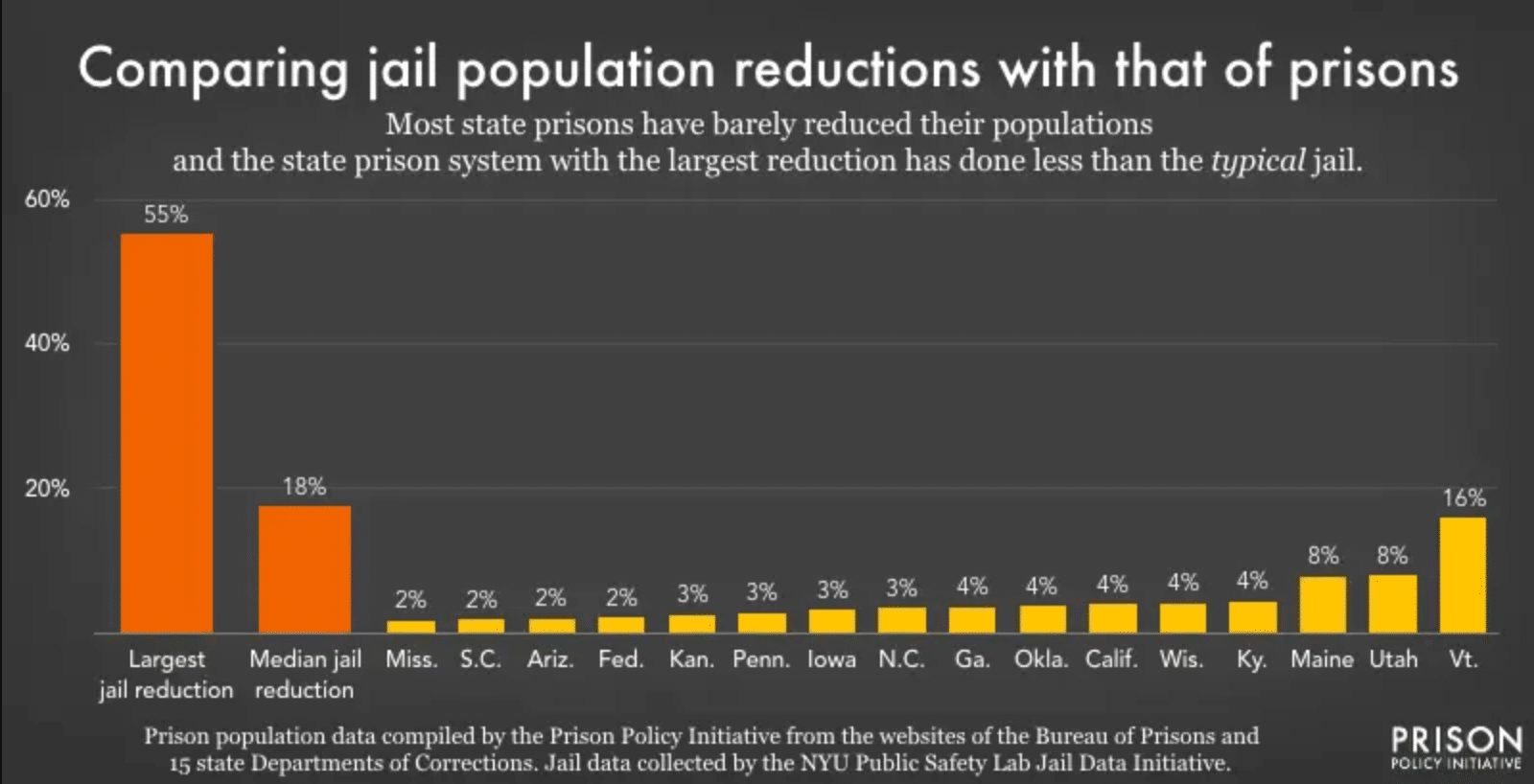

As of April 27, none of the population percentage reductions from the 15 state prisons with available, frequently-updated population counts surpassed jails’, according to a May 1 Prison Policy Initiative analysis. Even the highest state prison reduction—Vermont’s 16 percent—fell below the analyzed jails’ median reduction of 18 percent. And Vermont’s may not even be a reliable figure, since the state has a mixed jail-prison system.

“Because of this, we cannot be certain how much of Vermont’s incarcerated population reduction is due to the release of pretrial detainees (who would be in jail in other states) or people sentenced to state prison,” wrote Emily Widra, a PPI blog contributor, and Peter Wagner, the organization’s co-founder and executive director, “which suggests that even the state with most drastic prison population reduction is still too far behind the typical jail.”

PPI’s comparison of jail reductions with state and federal decarceration efforts. (Prison Policy Initiative)

The other 15 state prisons’ cuts range from 1.7 percent to 7.9 percent. Yet most jails have reduced their populations by at least 15 percent, and more than one-third have slashed them by a quarter.

States’ meek reductions may not even be true instances of decarceration, the authors suggest. At least four states—California, Colorado, Illinois and Oklahama—have refused to accept incarcerated people held at county jails into prisons. “While refusing to admit people from jails does reduce prison density,” they write, “it means that the people who would normally be admitted are still being held in different correctional facilities.”

By and large, states don’t seem to be doing what the PPI authors describe as the “obvious” measures to ease population density. They could be refusing to incarcerate people in on technical parole and probation violations, or they could front-load them for release—neither of which, “for the most part,” states are doing.

“States clearly need to do more to reduce the density of state prisons,” the PPI authors conclude.

Photograph of San Quentin State Prison in California by Zboralski via Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons

Show Comments