In the fall of 2020, COVID lockdown-induced depression triggered my incarceration-related PTSD and related suicidal ideation. So I looked into the bougie ketamine clinic I’d seen sponsoring a Los Angeles area highway. The cost? $6,000 for a month.

It was out of my reach. A gram of ketamine, about two months’ worth of therapeutic doses, costs around $100 on the illicit market. But that was out of my comfort zone and purview. Instead, I got prescribed Xanax and made it through.

My moods wax and wane, but the suicidal ideation is a constant. When my mood is low, the siren song is most tempting. When my mood is stable, the intrusive thoughts are little more than illogical annoyances.

Multiple psychiatrists had long encouraged me to try SSRIs. But an experience of being forcibly detoxed from Suboxone after turning myself into jail left me with lingering trauma around medications that require daily dosing.

In summer 2022, a bad breakup combined with a grueling workload pushed me over the edge. I acquiesced to my psychiatrist’s recommendation and started Lexapro. One month later, I nearly jumped off a building. Familiar suicidal ideation morphed into something new and terrifying: impulsive, active suicidality. My psych advised me to immediately discontinue the SSRI. A little while later I tried an SNRI, and cried uncontrollably for days.

“Your insurance may cover it,” were five of the sweetest words I’d ever heard.

That’s when, for the first time, a medical professional directly recommended I try ketamine.

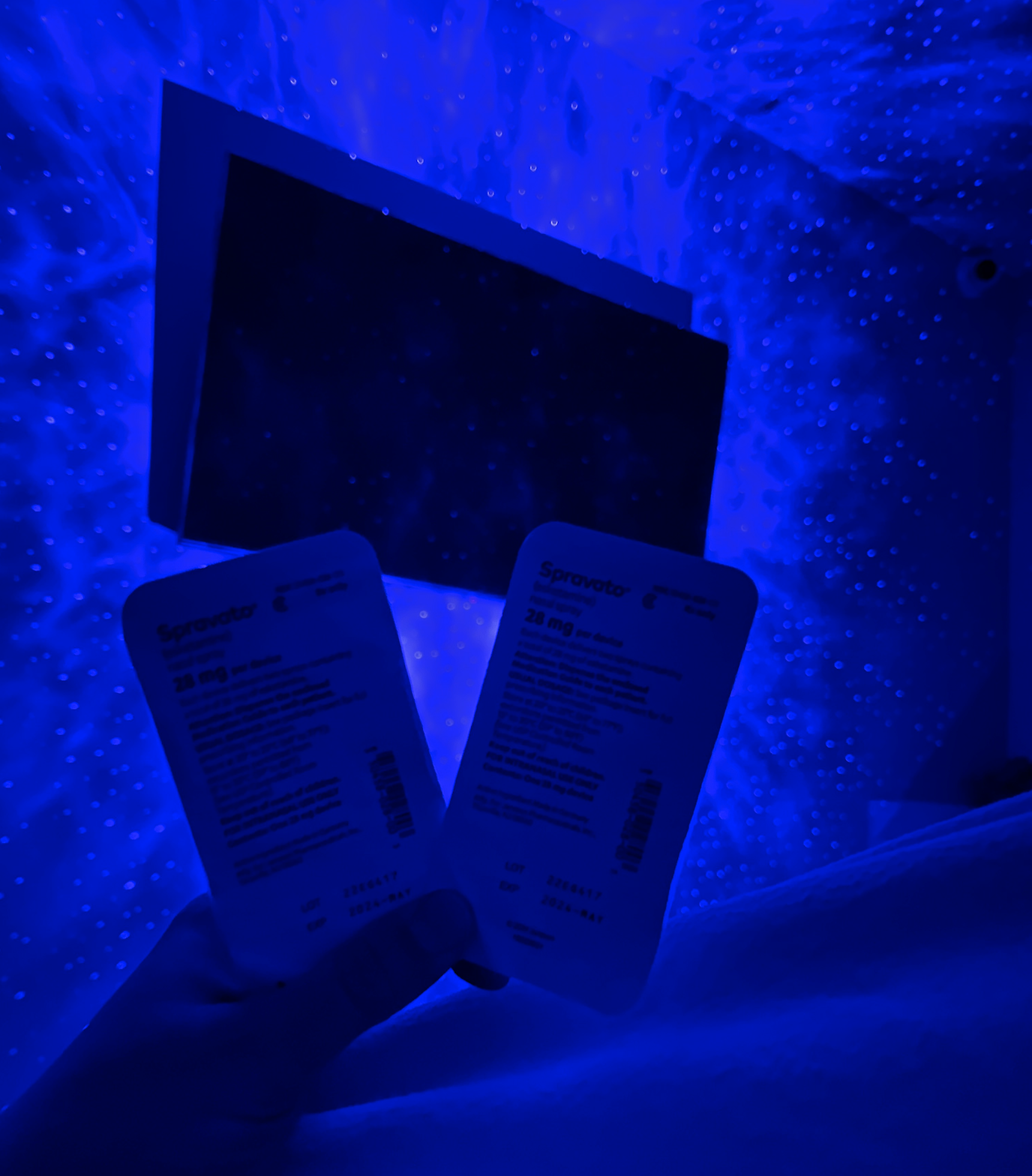

Specifically, she recommended Spravato, which is esketamine, an isomer of ketamine patented and produced by Janssen pharmaceuticals. “Your insurance may cover it,” were five of the sweetest words I’d ever heard.

Ketamine, first formulated in 1970, is a widely used generic medication. With a wide therapeutic index, it’s on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medications for its anesthetic and analgesic properties. Off-label, it’s shown efficacy in treating depression, PTSD and suicidality.

Health insurance will rarely cover ketamine for one of its off-label mental health uses, though. (Yet my insurance covers my propranolol, which is prescribed off-label for anxiety.) But mental health care has long received inferior coverage compared to physical health, even after the passage of a law designed to bring equity.

The scientific literature surrounding ketamine’s efficacy is ample and dates back decades. Esketamine, on the other hand, is expensive, less studied and less efficacious.

Why does my insurance cover esketamine, then? Because Janssen Pharmaceuticals invested millions in double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCT) to get it FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression. While many studies show ketamine as effective for depression, they are not of the holy-grail, double-blind RCT variety that the FDA demands.

Jacob Sherkow, a professor of law and medicine at the University of Illinois, and an expert on intellectual property and drug regulation, told Filter that insurance reimbursement for off-label uses is complex. “At times contrary to their economic interests, insurers tend to prefer on-label uses.”

Earning FDA approval—to win that golden on-label distinction—is an expensive and onerous process. Janssen did not do this with ketamine, of course. Instead, it isolated the s-isomer of ketamine, and put it inside of an nasal aerosolizer delivery device, creating a patented combination device.

Meanwhile, people who use unregulated forms of ketamine, a Schedule III drug—perhaps because they don’t have insurance coverage—still face arrest and jail. There’s also the familiar issue of drug-supply contamination.

I did my intake at a health clinic that offers intravenous ketamine infusions for cash payments ($495), and Spravato via insurance. Nestled in a nondescript medical plaza in Southeast Portland, the low-slung brick buildings and bubbling fountain gave little indication that behind the glass door, people were tripping balls.

Twice a week for the first month, then once a week as long as my insurance will cover it, up to 18 months.

I was an obvious candidate, being actively suicidal. Ketamine shows remarkable promise at reducing suicidality, with 69 percent of participants in one study showing marked improvement quickly. There was one problem: Spravato is only FDA-approved as a combination therapy, to be taken alongside SSRIs or SNRIs, even though it barely met criteria for producing statistically significant results. Seeing as that class of medication nearly precipitated a suicide attempt, my psych was unwilling to try another one. Thus began a months-long fight with insurance—an ironic protocol for someone who is actively suicidal.

The clinic eventually won a waiver, meaning I could do Spravato as monotherapy. The frequency is standardized: twice a week for the first month, then once a week as long as my insurance will cover it, up to 18 months.

My insurance, which I’m lucky to even have, pays out about $1,200 for Spravato but—typically—wouldn’t cover ketamine off-label, which would be much cheaper, though still require expensive sessions with providers. My total out-of-pocket expenses for this first month will be $280 in copays, plus the Uber rides necessary to get to and from the clinic.

When I finally got approved, the soonest available appointment was five weeks out. Demand for insurance-paid esketamine is high.

While I waited, I posted on Medium about starting Spravato. Janssen Pharmaceuticals emailed me at work, to ask for a correction for referring to it as “ketamine treatment.” Conscious of both its patent and anti-drug rhetoric, the company is devoting significant efforts to making the distinction.

And a hefty PR budget. A big red box showed up on my doorstep, unannounced. It was from Janssen and full of schwag: an intentions journal, Listerine breath strips and a head massager. Clearly, Spravato is not a generic medication with a narrow profit margin.

Day One

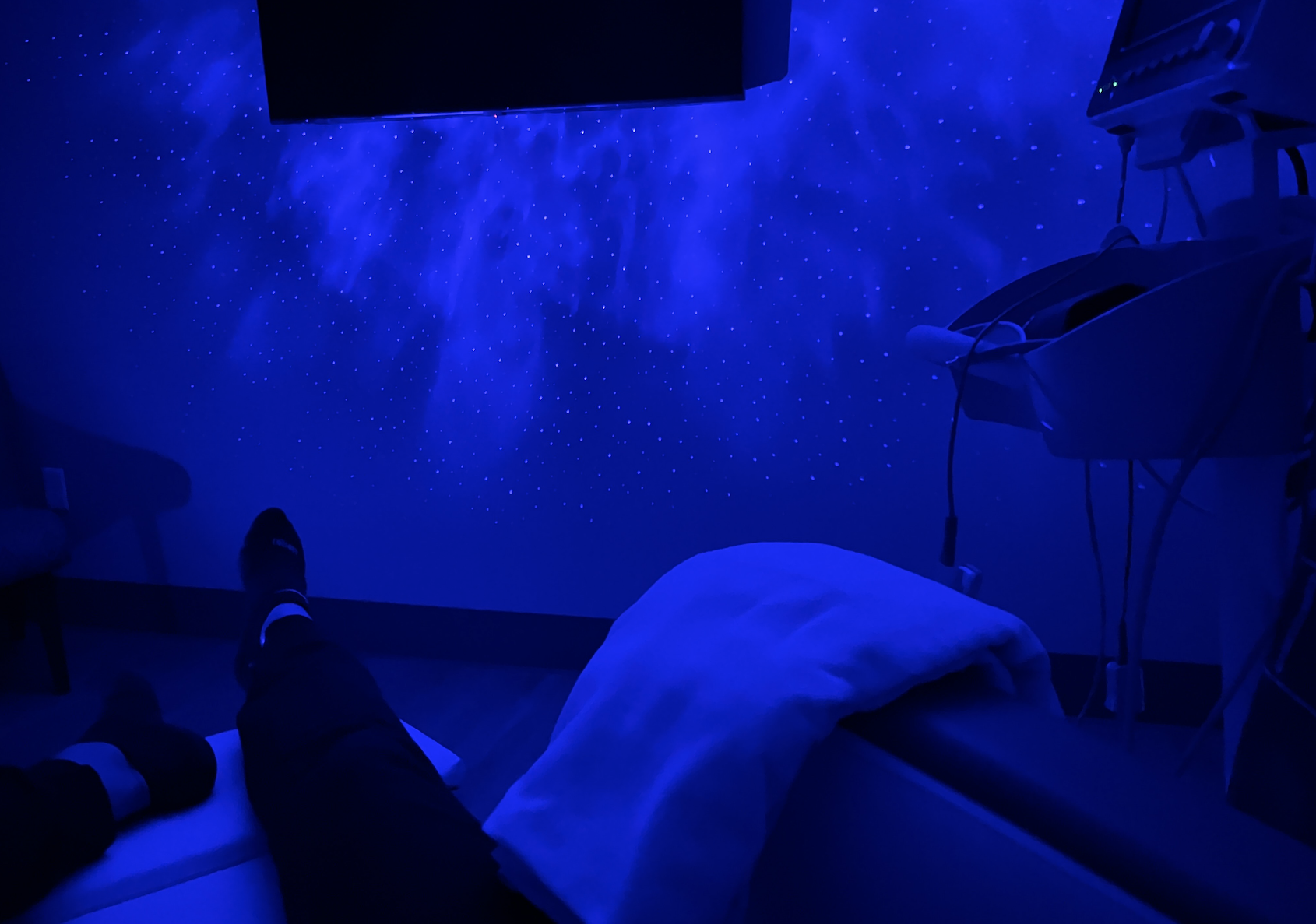

I showed up to my first appointment early and was led into a room that looked like a cross between a doctor’s office and therapist’s. A white recliner in the corner with an empty IV-hanger to the left. On the floor, the kind of cloud-and-stars blacklight projector you’d see at the home of the hippie who sells you weed, possibly purchased at Spencer’s.

A psychiatric nurse practitioner went through an excessively long checklist about everything bad that might happen, from high blood pressure to bladder issues to the psychoactive state of “dissociation.” I filled out a depression and anxiety score sheet, as I will do every session.

A technician took my vitals and offered me a quirky array of snacks and beverages. When I declined, they reminded me that Spravato is a nasal spray and tastes bitter. I opted for some Werther’s hard candies and a Kind bar. A tech brought me a heated blanket.

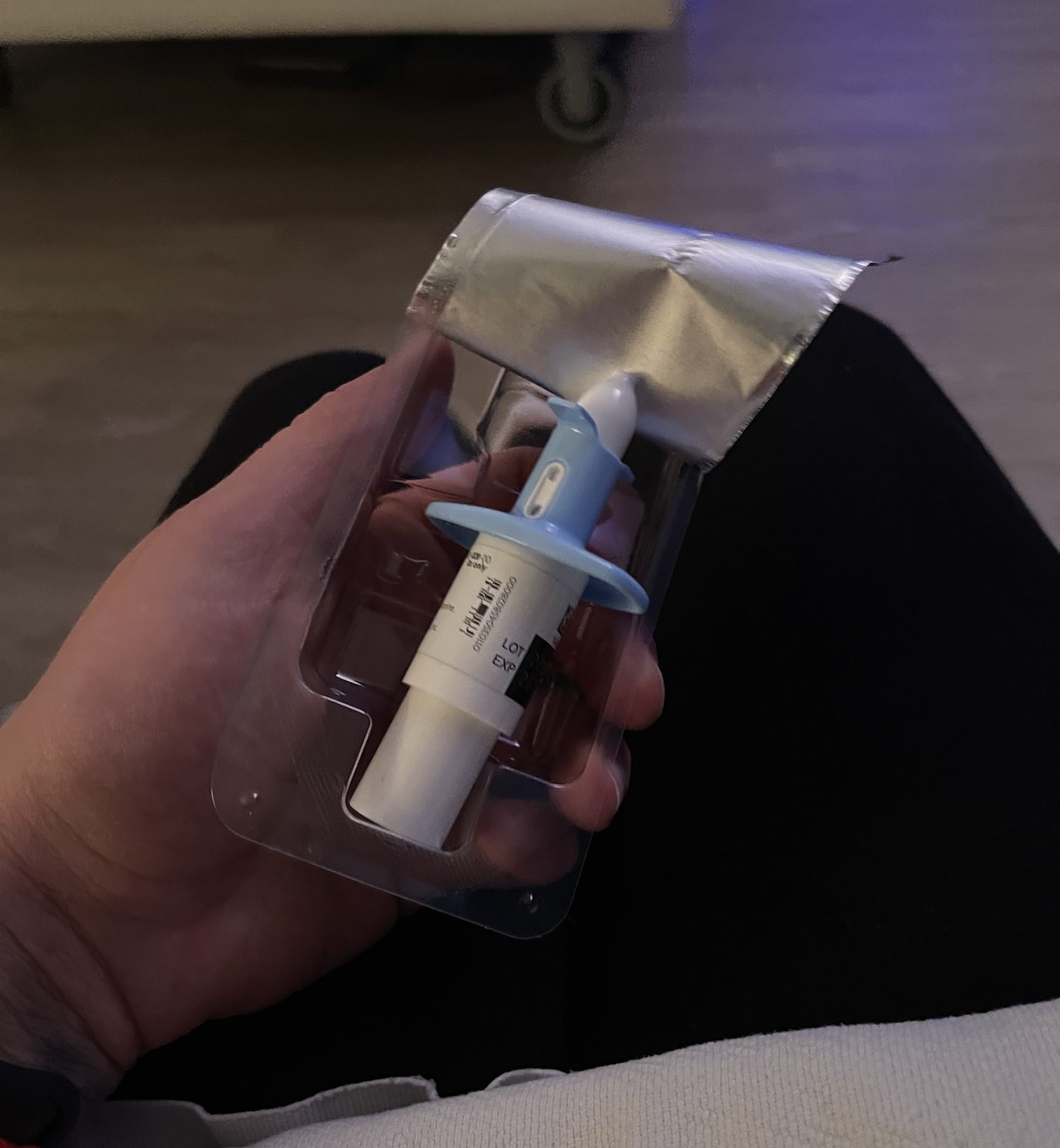

The first day’s dose is 56 mg. As an inveterate drug nerd, I asked about the bioavailability of this route of administration, and they told me 30-40 percent. I was shown the device: a 28 mg nasal spray containing two squirts’ worth, and displaying two green-to-white indicator dots.

The device was trickier than I expected, much more so than Narcan. I practiced the push-once-push-twice maneuver with a tester, alternating nostrils. Finally, I was ready. “Can I dose now?”

They turned on the corny lights-and-stars backlight, which is pleasant even when sober. They reminded me of the stars I saw on night watch during a recent sailing trip in the vast Pacific Ocean, one of the last times I didn’t feel suicidal.

My positioning was off, and the spray leaked out of my nose. They had me sniff and tilt my head back, similar to how I once learned to do cocaine.

I peeled the first device out of its plastic packaging, positioned my thumb over the plunger, and stuck it in my nose as far as its wings would allow. I fumbled trying to administer it, with the device requiring much more force than I’d predicted. I could barely detect the spray going up my nose.

Exactly five minutes after the first dose, the PNP handed me the second 28 mg device and I did each of its two 14 mg squirts in alternating nostrils. My positioning was off, and the spray leaked out of my nose. They had me sniff and tilt my head back, similar to how I once learned to do cocaine. Life always comes full circle.

After the second dose, the provider exited the room, leaving me alone with a security camera to monitor me.

I felt almost no effects. Eventually, I felt very bored. The law mandates they keep us for a full two hours after dosing. At the halfway point, a technician entered to take my blood pressure, which was elevated, as is standard.

How It Affects Me

Having to get a ride to the clinic and carve two hours out of my day, twice a week, is challenging. But so is crippling depression and the constant drumbeat of “kill yourself” dancing through my mind.

The second session that week was my first full dose, at 84 mg—three of the nasal spray devices at five-minute intervals. Unfortunately, the only time they had available was 9 am. It’s weird to trip and then have to return to work. It’s much better suited for an end-of-day activity.

Spravato works more slowly than ketamine infusions, and likely not as well. But patients across the country report: It does work—sometimes, for some people.

To explain how it affects me, I must first articulate how it feels to be bleakly depressed. It’s as if I am living life through a filter, one which dulls not only colors but tastes, sensations, smells and pleasure. Intellectually, I can see myself living a wonderful life, but it’s almost as if I’m watching someone else live it, unable to fully experience the joy I know I should be feeling.

My therapist calls this anhedonia. I do not always notice it in real time, as everything that makes my life worth living slips away into mundanity and tedium. I live muted to life’s pleasures but hyper-sensitized to its pains. I’ve struggled with this since I can remember.

The simplest of tasks feel impossibly behemoth. Dishes pile in the sink, texts and calls go unanswered, and unfinished work begins a guilt-and-shame tailspin that only worsens the procrastination that led to the mounting pile in the first place. Trivial errands fill me with dread and anxiety. God forbid it is trash day and I need to wheel my trash can to the street. It requires so many steps. When my flight is taking off and landing, or hitting turbulence, there’s always a moment I hope I’m crashing. Then I won’t have to have done it myself, but it will be over nonetheless. I immediately regret this when I realize there’s no way I’d be the only casualty.

Perhaps the first sign the fog of depression is lifting is a liked song on Spotify.

What does ketamine feel like? It’s a question that’s been asked countless times on Reddit and Erowid, and never quite answered. It’s an odd drug. Sensory perceptions distort, motor coordination diminishes.

The light machine in the dark room, I find, looks cool. I feel comfortable, like I could melt into the recliner. Music is the most tell-tale sign: it sounds cool. If I go to change the song, my eyes struggle to read against the digital screen. My cognitive function remains fairly intact but shrouded in disorientation. What speech I muster may be slurred, and my responses would be odd anyway.

A true ketamine high—which can be achieved by what is also considered a therapeutic dose, depending on whose protocols you’re reading in PubMed—separates the consciousness from the body.

All my compartmentalized, fractured selves and all my distinct dimensions collapse in on themselves. What exists in my robust virtual world versus my tangible, physical world gets jumbled, disorientingly, with both seeming to exist simultaneously. When my consciousness settles back in, slowly reconnecting its many tendrils to reactivate its integration with my body, it seems to do so having sloughed off much of the detritus that formed in that space between thought and action, the space where my depression lives.

Perhaps the first sign the fog of depression is lifting (a cliché, but they exist for a reason) is a liked song on Spotify.

I’ve always been passionate about music and will often have it playing in the background. I do this out of habit, even when depressed. What I do not do when depressed is really feel the music—think upon hearing a new song, “This is a great song!” before pressing the like button to add it to my library.

I’ll like a few new songs in a day, realizing how previously, I’ve gone weeks without adding anything to the library. If I could crunch the numbers, I guarantee my averaged liked songs on Spotify per week would inversely correlate with my depression.

The same correlation applies to how often I spot a sight worth photographing. I have long been known to stop anywhere to take a picture of something I find intriguing, odd or beautiful. But my ability to perceive beauty is diminished when I can only see the world through a sepia filter.

In our regulatory reality, Spravato is better than no ketamine at all.

I’m now on my third week of treatment. My copays and Uber rides are adding up, not to mention the effect of the multi-hour sessions on my schedule. But after next week, I’ll be dropped down to once-a-week sessions.

Intravenous medical ketamine would work better. I suspect the dosages of Spravato are designed to minimize psychoactivity—dissociation—because God forbid patients get high. (In large-scale clinical trials, too many middle-Americans experiencing dissociation would cause higher rates of unwanted dropouts.)

When I voiced my complaints about Spravato not working as well as ketamine could, the clinic seemed unsurprised. I was told to stick it out, but a few bad days had me considering a $495 ketamine infusion. Or suicide. You know, whichever.

Illicit ketamine would also work better and be cheaper than my copays, even. But because it’s a banned drug, I sit prisoner in a recliner for two hours, twice a week, to pay exponentially more for a less effective treatment for my life-threatening depression.

In our regulatory reality, Spravato—which is, before they email me again, not ketamine!—is better than no ketamine at all.

All photographs by Morgan Godvin