In 2006, a community health clinic opened in San Francisco’s Tenderloin District. On any given day, the waiting room would be filled with people at higher risk for HIV transmission, many of whom lacked stable housing or housing at all—drug users, sex workers, trans folks, people who were mentally ill and disabled. A community of people who weren’t welcome at other health care facilities.

Tenderloin Health was a groundbreaking institution. It was a place of harm reduction. It connected people with wraparound services no one else was offering, including housing; there were more housing clients than medical clients. It hired members of the community it served. Even me—a “crazy Black gay man” who was open about my drug use.

Around 2008, Tenderloin Health organized the city’s first public forum on safe consumption sites (SCS). It was full of drug-user activists and public health providers galvanized to end the drug war. In the discussions that followed, there was a split between those who wanted to work toward opening a city-run SCS, and those who wanted to open one with or without authorization.

We had a couple of meetings and public forums; they didn’t seem to be going anywhere.

Tenderloin Health closed in 2012; it didn’t have enough money to stay open. But the push for SCS still lived. In 2017, when Mayor London Breed was still president of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, she helped launch a task force to explore opening SCS in the city. I was one of the members.

We had a couple of meetings and public forums; they didn’t seem to be going anywhere. But we presented our findings at City Hall that October and made the case for SCS to open. A few weeks earlier, a bill that would have authorized local governments to decide whether to pilot SCS failed to make it out of the Senate, short by just two votes.

The director of the city’s public health department at the time, Barbara Garcia, publicly supported SCS. In 2018, she said we’d be opening two pilot sites. But a few months later she resigned, amid a separate conflict-of-interest scandal.

In 2020, the city passed an ordinance that would authorize SCS only if the state of California gave approval first. Later that year, Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed the bill to do so.

Breed has been saying she wants to repeal that 2020 ordinance and allow SCS to open with private funding. This would be a similar model to that of OnPointNYC—a private nonprofit using government funds for wraparound services, but private funding for the actual SCS services.

At the end of February, the Board of Supervisors approved that legislation. In May, Breed unveiled a budget proposal that included “wellness hubs,” i.e. SCS, in line with the private funding model. But many of us are skeptical, because it wouldn’t be the first time Breed and city officials gave lip service to the possibility of SCS. We even had one, and they shuttered it.

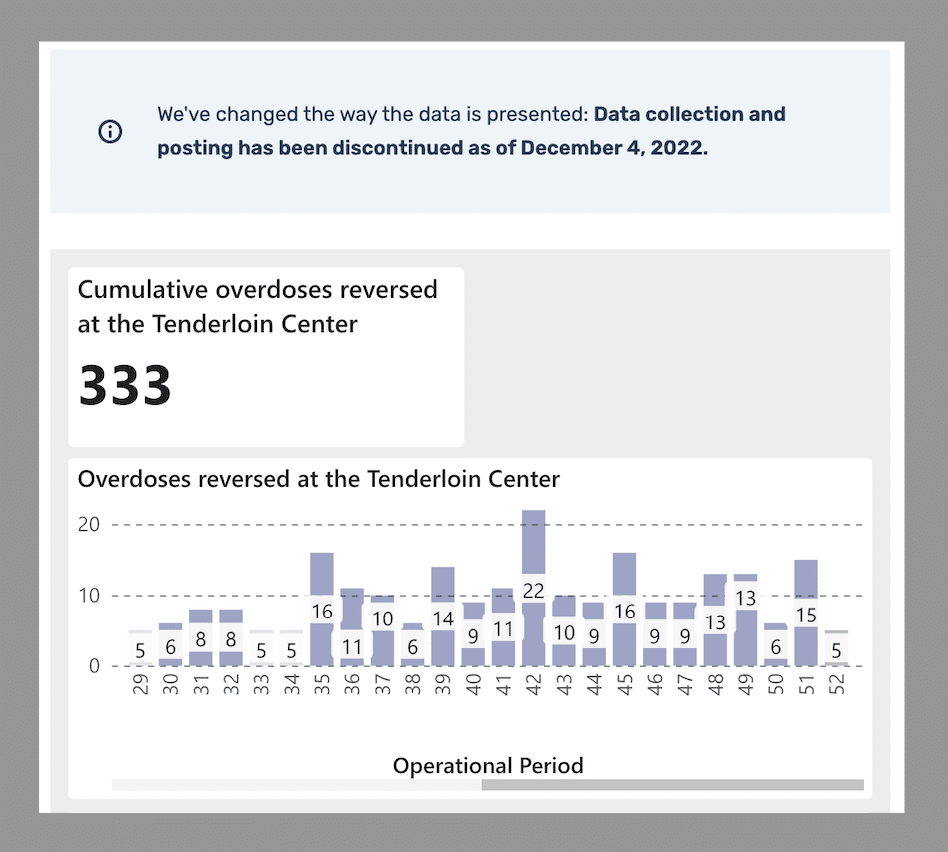

On January 14, 2022, a locally sanctioned SCS opened in the Tenderloin. Staff averted 333 overdoses before the SCS closed its doors in December. It didn’t have enough money to stay open—Breed had declined to renew the funding.

Preliminary data from the San Francisco Office of the Chief Medical Examiner show that the city recorded more overdose deaths in August 2023 than any other month on record. I wonder what the city could have been like today if government leaders were actually interested in the suggestions of their task forces, rather than exploiting the overdose crisis for political advancement

Mainstream media likes to portray San Francisco as extremely liberal, and scapegoat the Tenderloin for policies that in fact are increasingly conservative. Local government is taking more and more of a “tough-on-crime” approach that favors encampment sweeps, fentanyl-driven deportations and drug-induced homicide charges.

Breed has a vendetta against “open-air substance abuse,” but doesn’t seem interested in giving people a place to use drugs inside.

The Tenderloin continues to bear the brunt of all of it. Data from the San Francisco Department of Emergency Management show that in recent years, more than half the overdoses reversed by city-wide emergency medical services took place in the Tenderloin.

Rent keeps going up, and so do rates of homelessness, and of overdose. Breed has been on a vendetta against “open-air substance abuse,” but does not seem sufficiently interested in giving people a place to use drugs inside.

Instead, she’s focusing her energies on escalating the drug war. Her most recent move is pushing to make mandatory drug testing and treatment a condition of receiving cash assistance, as she stated in a September 26 announcement that current law doesn’t give the government enough power to “compel people into treatment” programs. The new initiative would “create more accountability and help get people to accept the treatment and services they need, [including] residential treatment, medical detox, medically assisted treatment, outpatient options and abstinence-based treatment.”

Breed thinks the city needs to “take back our Tenderloin”—from whom? Who does the Tenderloin belong to, if not those of us who live here?

Top photograph and inset graphic via City & County of San Francisco