Can you imagine that since the 1970s, the two federal agencies that control the methadone clinic system—the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)—have had the power to change rigid regulations so people with opioid addiction can more easily access the medication? And yet, aside from modest relaxations introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic, they never have—not even in the midst of a fentanyl-involved overdose crisis that claimed over 100,000 lives last year.

An insightful new report from the George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center, funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts, refutes the widely believed notion that the agencies weren’t empowered to enact reforms and that any changes would require an act of Congress—a daunting prospect given the legislative gridlock in Washington. Researchers Bridget C.E. Dooling and Laura Stanley provide ample evidence that in fact, the DEA and SAMHSA can modify or eliminate many of the regulatory barriers to getting methadone. Zero Congressional involvement needed.

SAMHSA has the ability right now, the report finds, to eliminate, exempt or amend some of the most onerous barriers to patients obtaining methadone.

The report goes into granular detail, some of which is dense with complex, legal arguments and jargon. But tables at the end of each section neatly summarize the information in simple language.

SAMHSA has the ability right now, the report finds, to eliminate, exempt or amend some of the most onerous barriers to patients obtaining methadone: daily dosing, urine screenings, mandatory ancillary services like counseling, the eight take-home criteria, and limits on take-home bottles.

The report states: “This regulatory authority gives SAMHSA the authority to consider exemption requests from opioid treatment programs on a case-by-case basis. SAMHSA used this regulatory authority to permit states to request exemptions related to the COVID-19 public health emergency. SAMHSA could adopt this same approach to remove or relax the patient care regulations by issuing a guidance document that invites exemption requests from states.”

Moreover, the investigation reveals how for over 50 years, the DEA has consistently chosen to interpret and enforce the most stringent and bureaucratic regulations on opioid treatment programs (OTPs) and patients.

One major obstacle to access is the DEA rule that prohibits doctors from prescribing methadone to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) outside of designated OTPs. Methadone must be directly administered to patients by a registered nurse via observed dosing. There is no other medication in the US pharmacopeia that is literally locked inside a clinic.

The researchers contend that pharmacy pick-up could increase treatment numbers because there are roughly 60,000 pharmacies in the United States, and only 1,816 OTPs.

“This regulatory approach limits patient access to methadone because it requires patients to travel to their OTP almost daily,” the report states. “This geographic and logistical constraint is often cited as a reason why more people are not in treatment.”

The researchers contend that the option of pharmacy pick-up could increase treatment numbers because there are roughly 60,000 pharmacies in the United States, and only 1,816 OTPs.

That is critically important to addressing the ongoing crisis when methadone is demonstrated to reduce mortality for people with OUD by half or more. Methadone is already stocked in most pharmacies, and it’s not widely known that methadone can be picked up at a pharmacy if it’s prescribed to treat pain.

This double standard is an artifact of discrimination against people who use drugs. The DEA has the legal authority right now to eliminate its de facto ban on doctors prescribing methadone and let patients pick it up at a pharmacy—without additional authorization from Congress.

The report also details how the DEA has the ability to categorize drugs as controlled substances and then assign them to one of five schedules (I–V). Methadone is classified as a Schedule II substance—those deemed to have both a medically accepted use and a “high potential for abuse.”

Buprenorphine—another medication used to treat opioid use disorder—is classified as a Schedule III drug, with fewer restrictions and controls. Dooling and Stanley explain in extensive detail how the DEA, working with the Health and Human Services assistant secretary for health, could transfer methadone to Schedule III.

Finally the report looks at the byzantine, nonsensical and costly accreditation, certification, security, and record-keeping requirements demanded by the DEA and SAMHSA.

“This report clarifies that federal agencies have discretion to lower barriers and improve access to methadone treatment for opioid use disorder. How will they use it?”

The DEA is obsessed with security. Here is one of the more absurd examples: OTPs are required to keep controlled substances in a safe, steel cabinet or vault that meets certain specifications. A safe or steel cabinet must be equipped with an alarm system, and if it weighs less than 750 pounds it must be bolted or cemented to the floor. Wow! The DEA would have you believe that methadone is as dangerous as plutonium!

The report’s Executive Summary concludes, “This report clarifies that federal agencies have discretion to lower barriers and improve access to methadone treatment for opioid use disorder. How will they use it?”

They won’t. The DEA, in particular, is opposed to fundamental reforms to OTPs. It is a fossilized, federal policing agency full of drug warriors who like the status quo. If it weren’t for the death and destruction that COVID unleashed across the country, both agencies would never have loosened restrictions on take-home bottles of methadone. The pandemic forced them to make one important but modest, temporary change that was implemented unevenly.

The problem with the “guidance” SAMHSA offered OTPs—to allow blanket exceptions to give patients 14 or 28-day take-home bottles—is that it wasn’t mandatory. It left the decision, to be made based on the agency’s discriminatory stable vs. unstable criteria, up to each clinic.

SAMHSA should permanently remove onerous patient care regulations. Short of that, Dooling and Stanley propose that the agency should “invite exemption requests from states.” For-profit clinics won’t apply for exemptions to regs if they affect their bottom line, in particular giving more take-home bottles. Daily dosing is a billing opportunity they are loath to give up.

In addition, expecting the DEA to reschedule methadone is a nonstarter. Hundreds of studies have demonstrated the harms of criminalization and the benefits of banned drugs. The DEA has never allowed evidence to change its position.

Hoping that the DEA and SAMHSA will use their power to fundamentally reform the methadone clinic system and end its culture of cruelty would therefore be naive. But none of us should be in any doubt that these agencies themselves are a huge part of the problem. As the report correctly notes, “…leveraging pharmacy access to methadone would potentially alleviate a major hurdle to treatment access.” That is the solution that will actually save lives.

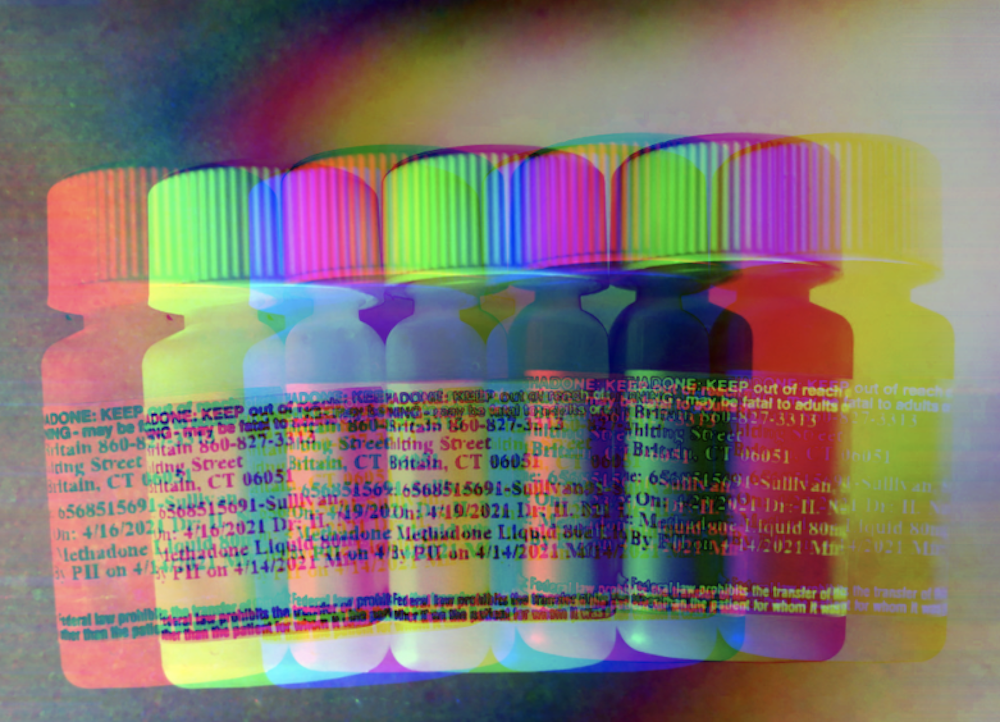

Photograph by Helen Redmond