For most of his time in Georgia Department of Corrections custody, Charlie was assigned to the horticulture crew. Over those 15-odd years he cultivated about three dozen gardens—herbs, flowers, fruit trees, vegetables. He was a walking botanical encyclopedia who cared for plants and nothing else, which made conversation both edifying and ungovernable.

Arrested for shooting at state deputies as they ripped his pot plants from Mother Earth, Charlie was serving a sentence of 20 years.

“I did not shoot at the police,” Charlie told Filter. “Just shot in the air to scare them away so I could fetch the harvest.”

The state of Georgia doesn’t split hairs this way. If you discharge a firearm in the presence of law enforcement, parole is not for you. Charlie knew he’d be maxing out his sentence. We had a deal that if he made it out, I’d share his story, after he’d gotten a head start.

With any luck Charlie is somewhere in the Blue Ridge Mountains by now, and will never be seen again. Almost all his horticultural knowledge will go with him, partly because we had no idea what he was saying most of the time. But we understood the mission behind it: an uphill, mostly single-handed battle against the malnutrition and inaccessible health care forced upon his fellow prisoners. That, more than the plants themselves, is his legacy.

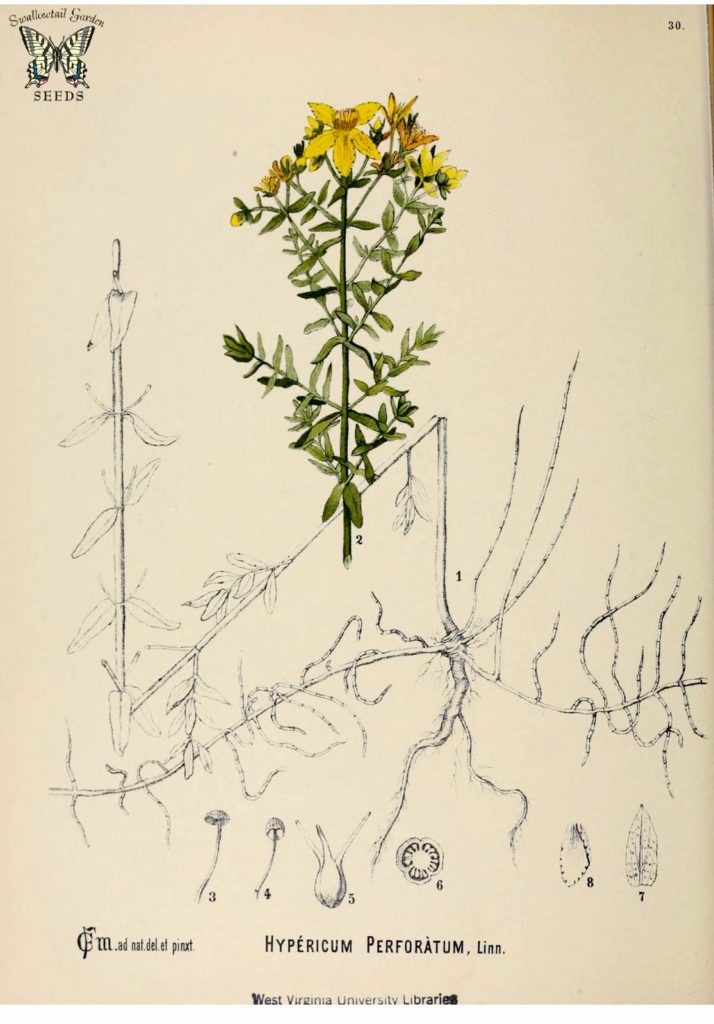

St. John’s Wort

St. John’s Wort

At the beginning of his sentence Charlie was assigned Close Security, the classification for those with a history of violence or a tendency to leave prison without permission. He was supervised at all times.

After a couple of years, he was reclassified to Medium Security. He was transferred to a new facility, one of the ones with flower beds by the admin buildings. He recognized some of the weeds: St. John’s Wort. Knowing of its antidepressant effects, Charlie helpfully set about weeding the garden.

“A deputy warden walked up and started telling me what he wanted done with the flower beds, and I said, ‘Sir, I’m not assigned to this detail,'” Charlie recalled. “And he said since I was showing an interest, I was the detail.”

Time passed. The deputy warden was promoted to warden, at a different prison, and Charlie soon found himself transferred there, too.

“He had made that happen and met me [at intake] to tell me in front of some other officers, ‘There’s wreck of a greenhouse here and it’s your job to make something of it,'” Charlie said. “Over the years, as all those people retired and were replaced, I just kept doing what I do and everyone has been cool with it.”

What Charlie did fell into two categories: Feel Better plants, and Feel Good plants. We’ll start with the Feel Better.

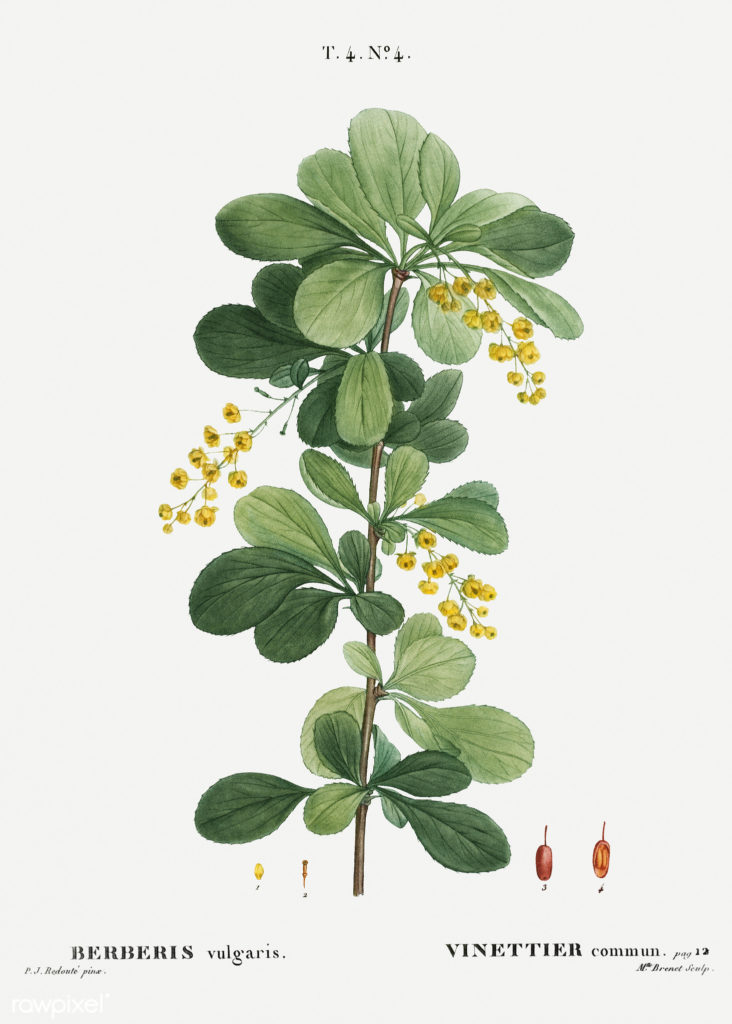

Barberry

An unlikely candidate for this prison was a barberry plant. South Georgia is not its ideal climate, but Charlie kept it reasonably happy moving it back and forth between the yard and admin hallway according to the weather. Boil a mixture of root and seed, reduce down by one-third, let cool. Makes kidney stone passage less of an ordeal, and doesn’t require forfeiting your commissary food to cover a co-pay from medical.

Behind one greenhouse Charlie cultivated dwarf fruit trees: apple, pear, orange, lemon, lime and cherry. The trees aren’t dwarf by nature, but by virtue of being kept in buckets—after all, they’re in prison too, and starved of the essentials all life needs in order to grow. Still, trees in buckets are portable and their roots are easy to trim. Charlie cloned them again and again. Harvest fruit, chop and dehydrate peels, powderize, add to tea.

“If the greenhouses were in better repair we could pretty much keep a rotation of plants and trees constantly in the various stages of producing fruit,” Charlie said. “But alas, it is prison. There is no budget for that.”

As Charlie tried to get us closer to our recommended daily vitamin intake, the lawn behind security grew elderberry bushes. Not to be confused with the purple-berried pokeweed. Pokeweed root is toxic if you take too much, but worked wonders on common colds when dosed knowledgeably as Charlie did. He grew this one mostly for the prisoners who use drugs, many of whom were brought tea the moment they started to get sick.

“Because you and I both know they won’t go near medical,” he said. “And it just keeps the cold going around and around.”

Flowering purple horsemint was for our gingivitis and toothaches. The chewable leaves were always in high demand; we don’t get dental until something needs to be extracted.

Charlie couldn’t do anything about whether or not asthmatic prisoners got their inhalers. But he made sure there was always a bed of wormseed in the garden over by the chowhall.

Bark and flower from the dogwood tree was fever-and-chills tea. Bark from the cascara buckthorn tree was laxative tea. Needles from the fir trees were the anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, antioxidant tea.

With a reduction of the pipsissewa flower, Charlie made a tea that helped with swelling, and as a poultice worked for sore muscles in general. Another poultice was white hellbore, to stave off infection from cuts. Part of daily life here from bumping into the fences along the walkways.

Somewhat incredibly, Charlie produced quinine tea from the bark from a cinchona tree. The tree is supposed to be in a rainforest somewhere but is instead in one of our greenhouses, where Charlie coaxed it into painstakingly slow growth and eventually a harvest that was small, but successful. A preferred cure-all of his.

Bloodroot

Bloodroot

During the summers, Charlie grew bloodroot and stockpiled the dried roots in a shed. By flu season, he’d have enough to make the decongesting tea that saw many of us through the winters. So when COVID first hit the prison, Charlie made tea.

At least 100 men with COVID symptoms drank this tea. Word of mouth brought it to the worst cases. It was vile, but two doses and somehow you’d be breathing easier. You couldn’t drink a third because taste buds were back to work.

No one cared what was in it at the time. When asked, Charlie said it was a base of his bloodroot tea, with add-ons based on symptoms. Mostly dried willow bark scrapings, and a yellow flower it seemed I was expected to know. What are its magical properties?

“It cures sarcasm,” Charlie said. “That is candle bush. Cassia alata. Long before penicillin this plant was the cure for syphilis and gonorrhea. Kind of handy to have around. Mostly we use it here as a poultice for foot fungus. It contains the fungicide, chrysophanic acid. But it also breaks fevers, so I added it to the COVID tea.”

No one, including Charlie, is swearing that any of this is the best-evidenced medical advice. But we don’t have that here. We had Charlie.

“One of the nurses in medical had me raise angelica—Angelica atropurpurea,” Charlie said. “She’s Wiccan and used it to relieve menstrual cramps. It is also used [for] respiratory problems. I used it in some of the teas for COVID. Did it help? Nobody died, but that’s no proof.”

Read Part 2 of this story here.

Images courtesy of California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation; Rawpixl LTD/Creative Commons 2.0; Swallowtail Garden Seeds/Creative Commons 2.0; Smithsonian American Art Museum/Creative Commons 1.0

Show Comments