If it were up to me, it’s unlikely I would be sitting down to write about my life with chronic severe pain, or the government policies and the social attitudes government encourages that generate unnecessary suffering for far too many Americans. I’d rather be going for a walk, doing some gardening or painting watercolors. But I have no choice.

According to the National Institutes of Health, nearly 50 million American adults suffer chronic pain. All face a system stacked against the pain patient. That’s why I decided to do something about it.

My pain became severe and constant in 1997. It began by suddenly waking me up in the early hours one morning, with the feeling of being skewered with a burning spear from the upper-left of my abdomen through to the middle-left of my back. It has been a permanent feature of my life that this constant pain is only controlled by taking opioid medications.

It took a year to get a proper diagnosis: pancreas divisum. This rare birth defect, a double-tailed pancreas, is a long-known cause of severe pain, though the mechanism behind it is unknown. I felt weirdly comforted by the knowledge that I was not the first person to complain that this hurts.

Other than the pain, my pancreas function is mostly normal. The opioid medications that relieve my pain also slow my intestines a little, making my function more normal than I’d had before. My frequency of nausea stays the same as I’ve always had.

When my pancreas defect was diagnosed, other problems were also discovered. My esophagus also had two defects—the upper half is floppy, the lower part rigid. And the top end of my stomach doesn’t close, making me vulnerable to acid reflux.

As a girl, I often heard, “No normal child gets this many bellyaches.” and “Tums aren’t candy.” My parents and teachers told me my stomach problems were all about not wanting to go to school. But I wasn’t just claiming bellyaches, I was often sent home for throwing up, and I barfed just as often on weekend and summer days as I did on school days. The adults didn’t seem to notice, but the other kids did. No one wanted to be in front of me on the bus, on the cafeteria line or in gym class.

Being a long-term, high-dose opioid patient means living under a suspected-murderer level of scrutiny.

In adulthood I mostly ignored my GI problems. If I needed to be horizontal, or only felt like eating bland food, it didn’t stop me doing things I wanted to do—college, travel, work, art, getting married.

Here’s a way to envision the effect of drug war policies on my life. I’ve had various health issues besides my pancreas: a benign colon polyp, thyroid nodule, breast fibroadenomas, endometriosis and uterine fibroids. Last year, a shoulder injury required surgery and physical therapy. My husband plays sports, and has had his share of sports injuries. But my pain—or rather, government-placed obstacles between me and pain treatment—creates 95 percent of the appointments, insurance expenditures and co-pays for my husband and me combined.

Being a long-term, high-dose opioid patient means living under a suspected-murderer level of scrutiny. The tangible form of supervision is the ‘pain contract”. Like all pain patients, in recent years, I’ve been required to sign contracts, usually yearly, by medical facilities. Most follow a model generated by the federal government.

Did I mention urinalysis costs me $200 per test?

The patient must adhere to conditions like paper prescriptions only, no phone-ins; an in-person appointment every 28 days; and urine tests and pill counts at any or all appointments, or on 24 hours notice any time I receive a call. Only one doctor and one pharmacy can handle the prescriptions. Other conditions can include no cigarettes, alcohol or illegal drugs (on the theory that pain patients must be discouraged from sliding into addiction), and being required to attend psychiatric or psychological appointments.

Did I mention urinalysis costs me $200 per test? (A multiple drug-screening kit sells at drug stores for $49.95).

Having only one doctor write my pain prescriptions doesn’t sound like a big deal, and usually isn’t. But when I had my hysterectomy, my OB-GYN didn’t want to release me without a pain prescription, which I was afraid to accept. My one prescriber was in a foreign country, with no internet access. Wanting to be released from the hospital because there was no medical reason for me to remain, I finally took—and later shredded—the hospital’s prescription. When I told my doctor he was ok about it.

Unlike an actual contract, only one party to a pain contract is required to follow any obligations. If a pain patient violates any of the terms, they can be abandoned. But following all the provisions is no guarantee of continuation of pain treatment. When my GP’s employer implemented an arbitrary limit on opioid prescriptions, the contract was irrelevant. Either my prescription would be cut by one-third, or I could go to a pain clinic.

I was fortunate, and for the past couple of years my clinic has been working for me. But, the federal government, state legislature, state boards for doctors, nurses and pharmacists, and my health insurer all have the power, at any moment, to end normal life for me—or for any Americans who benefit from opioid pain medications.

Common Suffering, Fueled by Media

Many other pain sufferers in my life endure terrible situations. After spinal stenosis surgery didn’t relieve his pain, a member of my family was prescribed Gabapentin, which caused dizziness and nausea without pain relief. A few years ago, prescribing an opioid would not have been routine.

A friend disabled by multiple injuries in the military got only acetaminophen for pain in his head, shoulder, hips and knees.

Two friends had kidney stones in the past year, and were not even offered opioids after the diagnosis was confirmed.

Another friend, awaiting a root canal last week, was warned by an acquaintance against taking his pain prescription. The guy issuing the warning said the government is trying to get rid of these drugs because it only takes three pills to get you hooked. My friend dismissed the claim. It’s extreme, but only by degree.

Many Americans have a hugely inflated sense of opioids’ ability to get you hooked, and to kill.

Thanks to blanket media coverage of the opioid-involved overdose crisis—which, while devastating, affects only a tiny proportion of all who use opioids, mostly people who are not prescribed these drugs and combine them with other substances—many Americans have a hugely inflated sense of opioids’ ability to get you hooked, and to kill.

The friends I mentioned are all old enough to remember over-the-counter codeine cough syrup, and coming home from the ER with an opioid prescription. No one worried then that this was a path to disaster or death.

Opioid overdose isn’t a blink-of-an-eye demise, unless there’s more than just the opioid. Injecting an opioid into someone who recently consumed alcohol can kill. More frequently, illicit-market opioids with substances added to stretch profits cause anaphylactic shock or Stevens Johnson Syndrome, with rapid, deadly shutting of airways. Mixing opioids with benzodiazepines can be deadly. But when Ohio attempted an execution via lethal injection using hydromorphone and midazolam (an opioid and a benzodiazepine), the condemned man struggled, gasping, for almost half an hour before dying.

Actual opioid overdose is slow and simple to interrupt. If uninterrupted for between one and 12 hours, the person can slowly stop breathing altogether. If the process is interrupted, the person survives with no permanent organ damage.

It is because of inaccurate and inflated claims about opioids—exaggerations of their potential involvement in addiction and death—that so many Americans have been suffering needlessly with untreated or under-treated pain.

Rising to the Challenge of Pain-Patient Activism

Opioid restrictions are worthy of First Amendment-based action. But pain patients have particular obstacles to exercising the right to assemble to petition on our own behalf. Without adequate medication, many pain patients can’t just head out to the streets, and so we remain invisible and silent in our suffering.

I was thinking that when pain patients gather, such as the Don’t Punish Pain Rallies, held at state capitols, an inflatable couch could be displayed at the event to represent all the people at home whose pain prevents their in-person participation. But those who are at home, while represented, would still not be they part of the action. If it were me, I’d still feel left out.

A message in a bottle sent from a desert island—a way for an invisible, suffering person to reach out to strangers who just might be able to help.

I began to think of the possibility for us to use the internet to make contact, share experiences and maximize our visibility. One article at STAT, for example, about increasing opioid prescriptions, has a long comment thread that has long been hosting posts by and discussions among pain patients.

I pondered the idea of combining internet and real-world activities to boost pain patients’ visibility and connections. The internet is a powerful tool, but real-world activities can reach different audiences and create fodder for further online discussion. Posting videos, photos and interviews is a way to create a growing archive of our activities. The most difficult part was how to engage the pain patients with untreated and under-treated pain, the people with the least capability to take to the streets.

Considering this need, I recalled the ancient trope of a message in a bottle sent from a desert island—a way for a stranded, invisible, suffering person to reach out to strangers who just might be able to help.

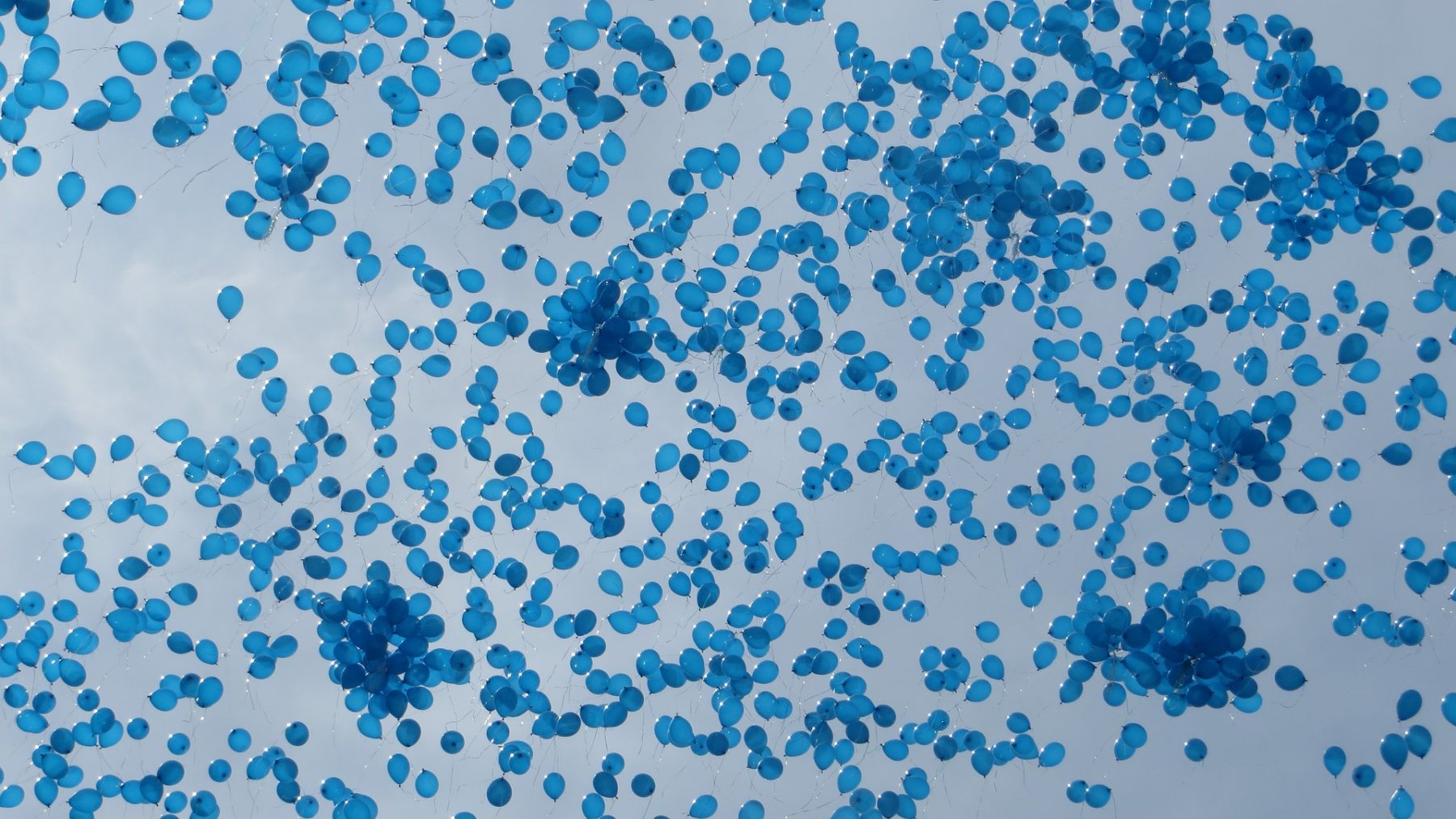

What I came up with is the Blue Balloon Campaign. Instead of floating our message in the ocean, we would float it in the sky.

The idea is that participants who are mobile will release balloons en masse from public places and distribute flyers to passersby; homebound individuals will launch balloons from their homes. This mechanism for people who suffer alone to be fully involved is vital. Other options include sending a balloon bouquet with a note—or a letter with the Blue Balloon logo—to a government official. The public will see these collective and single balloons, either in real life, or later in online videos and photos. Altogether, it should be a powerful symbol of just how many of us there are out there.

Our Day of Action—the first of its kind—takes place on Wednesday, May 15. A midweek day represents pain patients’ use of opioids to function within the community, to participate in the ordinary things that make up our lives: work, family, volunteering, travel and everything else that others take for granted.

If I had to describe the Blue Balloon Campaign on a scrap of paper in a bottle to be thrown into the ocean, here is what that message would be: Harsh laws, supported by falsehoods created and amplified by government, are sentencing too many Americans to unnecessary disability and suffering.

Show Comments