Safe consumption sites don’t just protect people from fatal overdose within their walls, suggests recent research.

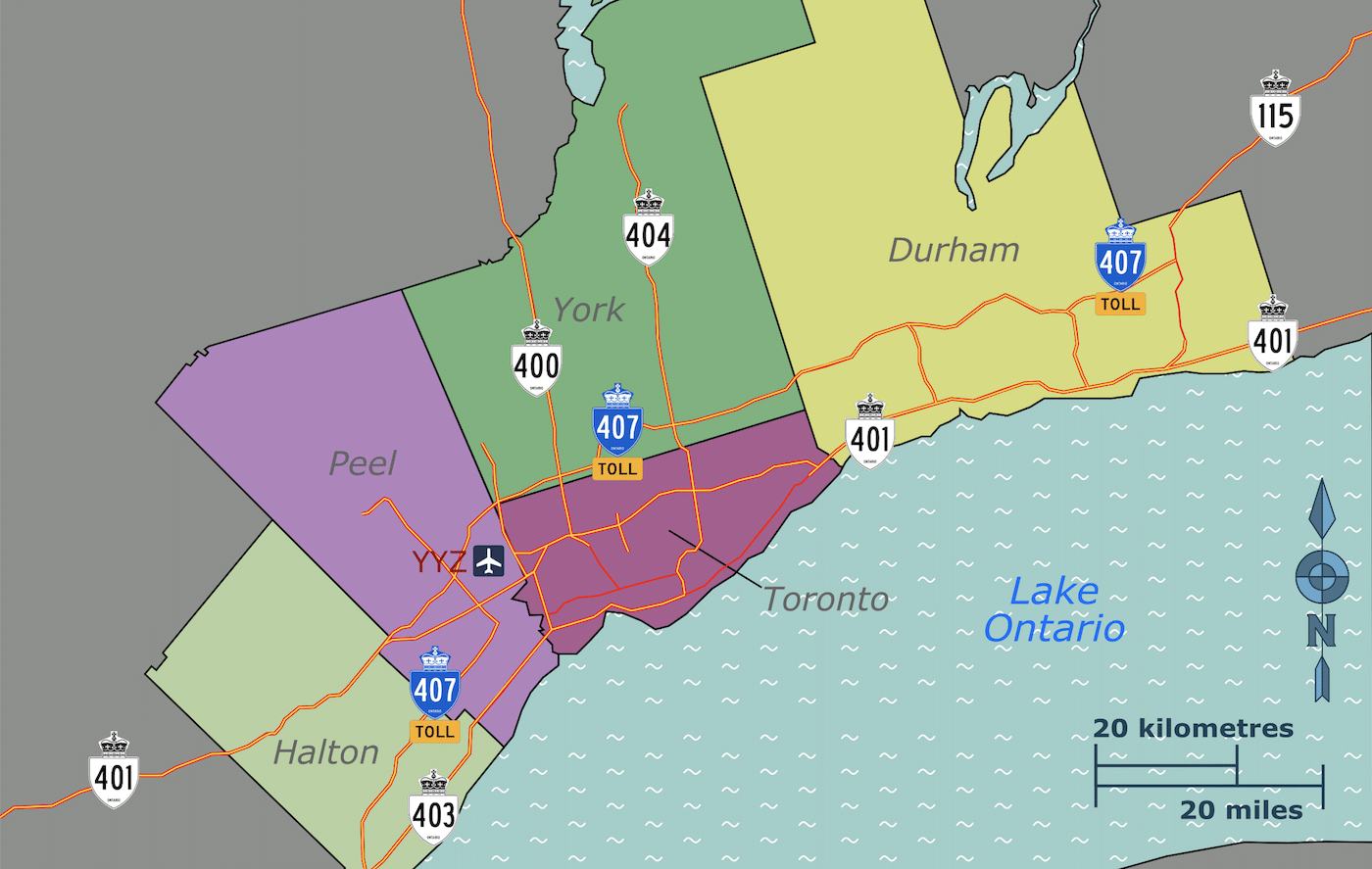

The study, published in the Lancet Public Health journal in February, examined overdose mortality incidence in Toronto between May 2017 and the end of 2019, a period when nine supervised consumption services (SCS) opened up around the city.

Comparing before and after, the researchers found a stunning 67 percent decrease in overdose fatalities in neighborhoods within 500 meters of SCS that had begun operating.

“In a geographically weighted regression analysis that adjusted for a range of neighborhood-level variables, we found an inverse association between the location of SCS and that of overdose fatalities,” they wrote.

A decrease in mortality “remained significant (though slightly weaker)” as far as 5 kilometers away from a site.

In other words, the apparent protective effect associated with an SCS is stronger the closer you are to it. But a decrease in mortality “remained significant (though slightly weaker),” the authors wrote, as far as 5 kilometers away from a site.

Why would this be?

SCS are characterized by the fact they allow people to use banned drugs on site, with naloxone, trained personnel and other resources on hand to intervene if an overdose occurs. But they don’t stop there: They also distribute naloxone and safer-use supplies, and provide referrals and connections to other vital health services.

“We posit that [fatal overdose] rate reduction at larger distances is potentially a result of naloxone dissemination across neighborhoods,” the authors wrote, “or an indirect effect of SCS acting as sites of low-barrier referrals to opioid agonist treatment, which is protective against overdose mortality.”

Harm reduction information is another important aspect of what SCS provide. And it’s incredible to think of a kind of ripple effect among drug-using communities: people better equipped, better connected and better able to survive, thanks to these programs.

“What we know about [SCS], whether you like it or not, is that they produce a sense of community among clients and the broader network of people who visit them and are served by them,” Dr. Daniel Werb, one the study authors and director of Toronto’s Centre for Drug Policy and Evaluation, told the Toronto Star. “From a public health perspective, that’s a good thing.”

Werb called the two-thirds reduction in mortality in surrounding areas “pretty amazing,” and he’s right. This powerful new evidence of the impact of SCS on wider communities could also boost advocacy for the services in the United States and elsewhere.

“These are neighborhoods with the highest concentration of overdose mortality, so seeing deaths decrease suggested a spatially-dependent positive spillover effect.”

Indhu Rammohan, MSc, was the lead author of the research. She studies at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, but completed this study for her masters thesis while attending the University of Toronto. She also works for the Centre for Drug Policy and Evaluation.

Many SCS “are co-located or partnered with existing community health services so they can connect people with primary care, treatment options, and a range of social services,” she told Filter. “There has never been a fatal overdose at one of these sites.”

That striking “never” applies despite SCS having operated for decades, in Europe, Australia, Canada and more recently in New York.

I asked Rammohan how the new research was conceived and developed.

“There was a lack of research using population-level metrics to evaluate supervised consumption sites—particularly in the context of the current synthetic opioid-fueled overdose crisis—and it seemed that this was an important piece to consider along with the existing evidence base,” she replied. “Dan Werb, my advisor, introduced me to spatial epidemiology and we envisioned how we could apply these methods to evaluate the asynchronous implementation of multiple supervised consumption sites in Toronto.”

Spatial epidemiology, as the term suggests, concerns the distribution of health outcomes across locations.

“We found that implementation of supervised consumption sites was associated with a reduction in overdose deaths in surrounding neighborhoods” Rammohan continued. “These are the neighborhoods with the highest concentration of drug use and overdose mortality, so seeing deaths decrease in these neighborhoods suggested that there may be a spatially-dependent positive spillover effect associated with supervised consumption sites.”

Rammohan then described three steps the researchers took to arrive at their findings.

First, they looked at overdose mortality data before and after the opening of SCS in different locations. Second, they mapped overdose deaths to see where they were heavily concentrated. And third, they controlled for population-level factors—neighborhood characteristics of overdose mortality and other health services operating in the vicinity—and looked at overdose rates in relation to the proximity of SCS.

“This research offers another dimension to the evidence supporting SCS … and our findings can further inform policy planning to this end.”

The result was compelling data to enhance a wealth of existing evidence supporting SCS, including large numbers of overdose deaths directly averted, reduced transmissions of HIV and hepatitis C, and more. Still more research has refuted opponents’ talking points, demonstrating, for example, that SCS do not increase local crime rates.

In 2021, On Point NYC made history by opening the first two sanctioned SCS in the US, termed overdose prevention centers, in East Harlem and Washington Heights. Since then, according to the organization’s website, the facilities have served 4,486 participants, monitored drug use 117,559 times, intervened in 1,339 overdoses, and safely disposed of 2,000,000 “units of hazardous waste,” such as syringes.

If that’s not success, I don’t know what is. But although a handful of states have now authorized SCS or moved toward doing so, progress is agonizingly slow during an unprecedented overdose crisis. So I asked Rammohan what she thought her research could do for US advocates.

“In the absence of federal support … this research can be used by local and state governments that are considering expanding their strategy to prevent overdose deaths and related harms using an evidence-informed approach,” she said. “This research offers another dimension to the evidence supporting supervised consumption sites … and our findings can further inform policy planning to this end.”

Image (cropped) by SHB2000 via Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons 4.0