Since early 2023, I’ve been surfing my way across what feels like every New Jersey substance use disorder treatment facility that takes Medicaid. In that time I’ve worked my way down from 140 mg methadone per day to 60 mg. I’m about to check in to lucky number 13, which will hopefully be the last one before I get down to 30 mg and make the jump to buprenorphine.

Treatment and recovery centers tend to be very moralizing places, and you’d think a lot of the people who work at them would approve of someone wanting to stop using all opioids including prescribed methadone. But mostly these providers don’t want to be involved with methadone at all, even to get someone off of it. The ones inclined to help still haven’t known how, because they’ve never heard of someone doing it this way. But as much bureaucracy and judgment as I’ve voluntarily subjected myself to in the rehab system, it’s worth it to bypass the methadone clinic system.

In New Jersey at least, the treatment facilities that take Medicaid will start you at their short-term programs—usually 28 to 35 days. Or 21 to 28 days, if you spent your first week going through their detox. A lot of the ones I call are non-starters because they don’t provide methadone at all, or they’ll only work with you if your dose is 40 mg less. A lot of the places that do provide methadone are still non-starters, because they make it clear that whatever dose I come in at, they’re going to keep me there.

First I write a “sick call,” and within the next three to five days I see a provider. That’s when I explain my plan.

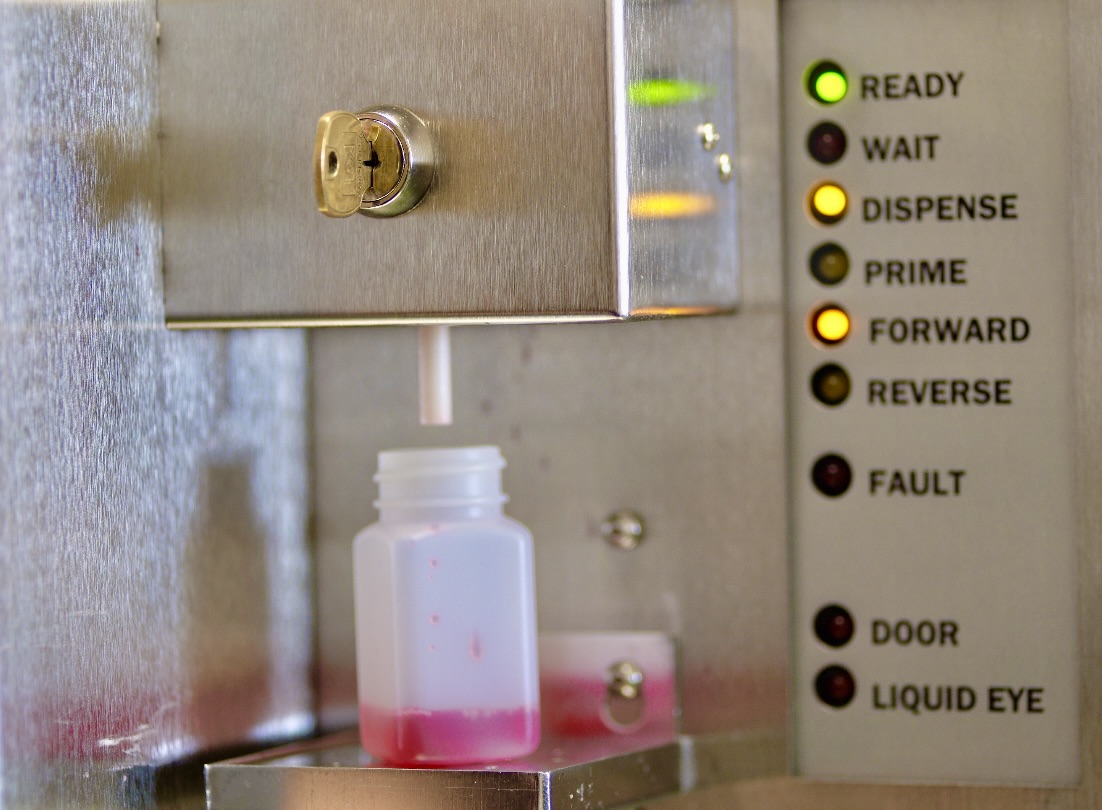

The facilities I’ve stayed at so far have been the ones that told me I’d be able to manage my dose myself, higher or lower, no problem. Of course, sometimes that would change once I was done signing the paperwork. But either way, for the minority of patients on methadone these facilities will run a little in-house mini clinic. Line up every morning for your cup of Methadose, drink it in front of them, drink a cup of water, speak some words, drink another cup of water, say some more words until they trust that you’ve swallowed it. But generally they’re less inclined to make your life miserable than their counterparts out in the real world.

First I write a “sick call” slip saying I want to adjust my dose, and within the next three to five days I see a provider. That’s when I explain my plan—every seven to 10 days they can lower the dose by up to 10 mg, so I tell them I want to drop 10 mg per week.

If all goes well then a month later I’m discharged into their longer-term program, which lasts three to four months. Or if by the end of that month I hate the place, as I often do, I make a lateral move to another facility’s short-term program. Or sometimes I can go straight into their long-term.

After that the next stop on the conveyor belt after is a halfway house, but I usually jump off before then. Unless I haven’t figured out the next roof over my head, halfway houses don’t make sense for me—no methadone dispensed on the premises. They just send you out to a regular clinic every morning on your own, which is what I’m in rehab to avoid in the first place. So once I’m discharged from a long-term program, I go to the short-term at a new facility and start over.

Like homeless shelters, these places share a lot of common elements with jails and prisons.

For my purposes at least, the short programs are too short. The long programs are too cult-y. All of them are too much like jail.

Like homeless shelters, these facilities share a lot of common elements with jails and prisons—more than just the urine testing and bunk beds and general surveillance. At one place they didn’t even tell me that at night they locked everyone inside the building. Had to get myself kicked out of that one in order to leave.

None of them let you have a cell phone during your stay. The reason is always that they don’t want anyone making a private phone call and then heading out to buy drugs. One place kicked me out when they found my phone, which is the kind of thing that makes a person head out to buy drugs.

Vapes aren’t allowed, for basically the same reason; they just assume you’ve put marijuana in there. In my experience about the Medicaid facilities are about 50/50 in terms of whether their policies allow residents to have cigarettes, but I’ve never heard of any that will allow you to vape. The only residential facilities I’ve heard where you can have vapes are the “sober living” houses, which unlike the halfway houses are privately run and not tied to Medicaid. If someone’s paying out of pocket, no one cares what they do.

Most people I go through rehab with aren’t there because it was their idea. Sometimes it’s because their family pressured them, but a lot of the time it’s because of drug court. Over time, the more I’ve talked to other patients the more I’ve noticed that the ones who come in by way of drug courts get a lot more leeway than the rest of us. The general feeling is that the people who run these facilities want to stay on the good side of judges who refer people into their program, so they’re not in as much of a rush to do an administrative discharge over a cell phone.

Unlimited Xanax and Klonopin helped me drop from 170 mg to 90 mg in under six weeks.

I first got on methadone in 2009 and stayed on it until 2014. This was right before New Jersey prescription drug monitoring programs expanded their reach, so I had a dozen prescribers at a time writing me whatever I could pay for in cash. Unlimited Xanax and Klonopin helped me drop my methadone from 170 mg down to 90 mg in under six weeks.

I wasn’t in any residential program at the time. By the end I wasn’t even in a methadone program—I’d lost my take-homes due to a “community violation” (got arrested) and since I happened to have a stockpile of take-home bottles at home and was super pissed at the program, I figured I’d do the last leg on my own.

It’s hard to imagine the stars ever aligning quite like this again, but I actually pulled together my own case management team. I had a primary care physician, a talk therapist and an addiction specialist who were all in communication with each other and would check in with me on conference calls. When I got my methadone down to 30 mg, the addiction specialist prescribed me a 10-day supply of the 30 mg roxies (AKA oxycodone) to bridge me through the transition to bupe.

The roxies only lasted a couple of days, but that was okay. Since I was doing this unsupervised, I could just keep going to get the benzodiazepines that saw me through the rest of the way.

And it worked. I got off methadone. I spent the next three years with a 24 mg prescription of Subutex, which I never had to take in full if I wanted to take less. Around 2019 I started screwing around with street supply again, which had become fentanyl-based in the intervening time. But in between I had a great year or so of just … being normal. Being treated like I belonged in the world.

A lot of programs won’t even help you move from methadone to bupe, let alone prescribe Xanax along the way; too much paperwork. So access to benzos—or to whatever actually works for you, in whatever amounts actually work for you—is the upside of doing this on your own. It’s also the downside of doing this on your own, you’re inevitably putting yourself back in the same environments you’re trying to get away from.

I hold no ill will toward methadone. It served its purpose.

Even at 60 mg, I’m feeling the nod much more deeply than I want to. But I hold no ill will toward methadone. It served its purpose. It kept me alive through the shitshow of the early pandemic, through neighborhood sellers trying to figure out their xylezine ratios. I hold a lot of ill will toward the clinic system.

I don’t know anyone else whose methadone taper took anywhere near this much time. I didn’t realize I’d be doing it this long when I started, but of course it hasn’t been a linear process. I’d often lose a lot of progress during the transition from one facility to the next. Two steps forward, one step back, that kind of thing.

But I feel good about what I’m doing. It’s been a winding path, but I’ve managed to avoid setting foot in an actual clinic, which is saying something. And I’ve learned a lot about myself over the past year or two. I’ve spent most of my rehab time journaling, as there isn’t much else to do in the Medicaid places. You get what you pay for, which is nothing. And a much better deal than you’ll get from the clinic system.

Image via Helen Redmond and Marilena Marchetti