The only treatment interventions associated with reducing an opioid use disorder patient’s overdose risk are buprenorphine and methadone, according to a new study. But only a minority of OUD patients are actually on these medications—and most are not even on them for long enough to reap the benefits.

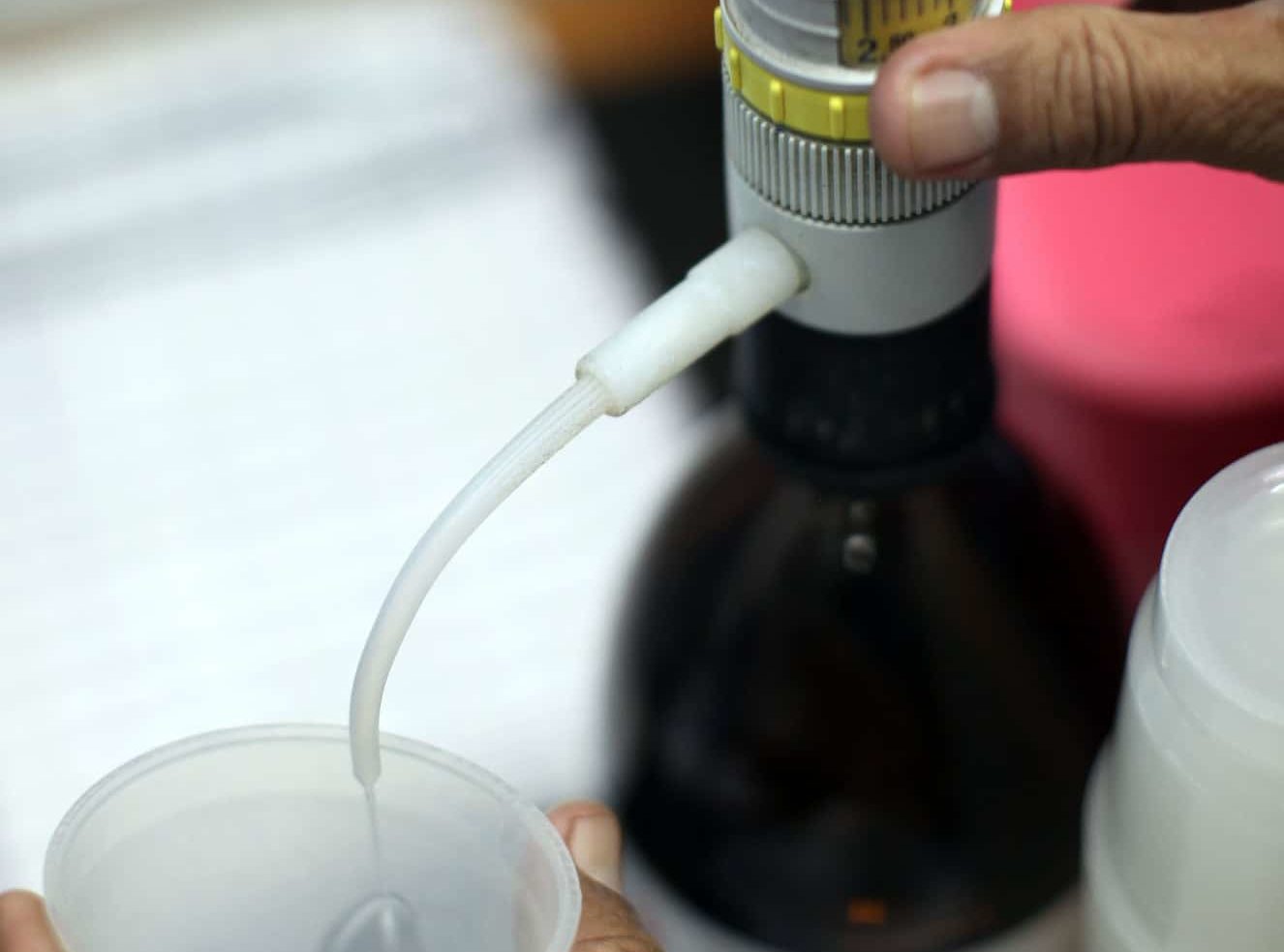

Out of more than 40,000 people with OUD, patients who took buprenorphine or methadone for at least 12 months saw the greatest reduction in overdose, found a February 5 study published in JAMA Network Open. Around 3 percent of patients who did not receive medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) had experienced an overdose at the end of a one-year period, whereas only 1 percent of patients on MOUD for that time period had such an experience.

No overdose risk reduction was associated with any of the other interventions studied—even with the two most common ones, non-intensive behavioral health services (59 percent of study cohort) and inpatient detoxification or residential services (15 percent of study cohort).

The third type of MOUD included in the study, naltrexone, did not show risk reduction either. Naltrexone requires detoxification, whereas methadone and buprenorphine do not. As shown in studies of outcomes for people who have been released from prison, the risk of a fatal overdose is greater when someone has been detoxed. Naltrexone manufacturer Alkermes did not track overdoses among participants in its only study.

The duration of a patient’s retention in MOUD treatment was associated with risk reduction. Taking the medication for less than a month was actually associated with much higher risk of overdose, with 6 percent of patients who took MOUD for between one and 30 days experiencing an overdose. But after 180 days or around six months on the meds, the likelihood of overdose dropped by five percentage points.

Yet the average duration of buprenorphine and methadone treatment among the study cohort was 149 days—a month short of the time period when the anti-overdose benefits seemed to kick in.

This is especially concerning when patients’ access to methadone and buprenorphine is shaky. Patients on the medication had the highest rates of health insurance disenrollment, while those in non-intensive behavioral health interventions, which are seemingly ineffective at reducing overdoses, saw the lowest.

The study authors note the existence of “numerous” other barriers to “sustained engagement” in methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Among them include “lack of access to waivered practitioners, high co-payments, prior authorization requirements, and other restrictions on use,” write the authors.

People of color were underrepresented among patients on methadone and bupernorphine, while white people were overrepresented. Black people made up 12 percent of the total cohort, but only 9 percent of folks on the meds, while Hispanic patients were 8 percent of the total and 4 percent of those on MOUD. White people were nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of the total, but 78 percent of those taking buprenorphine or methadone.

The study authors suggest that low-threshold treatment programs could be a way to boost retention.

“This is not about being ‘pro-medication’ or ‘anti’ other treatments,” tweeted study author Dr. Sarah Wakeman, an addiction medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. “I am pro science, pro things that keep people alive, healthy, & happy. Patients & families deserve evidence to make informed decisions that are right for them. Just like with any other illness.”