The US has historically been resistant to supporting harm reduction programs for people who use drugs. While some object to harm reduction approaches on ideological grounds—i.e., abstinence is the only way, drug use is immoral—most reject interventions like syringe exchange programs and maintenance medications based on commonly held myths.

Despite considerable research evidence being available to dispel such myths, confusion about common harm reduction strategies has stubbornly persisted in the wider population, preventing them from becoming mainstream.

Recent public interest in finding innovative solutions to the opioid-involved overdose crisis provides an opportunity to revisit long-held misconceptions. Policymakers owe it to their constituents to base their decisions about which interventions to support on the best available evidence.

While many US harm reductionists are today advocating for “radical” approaches that also have proven efficacy, like safer consumption spaces and heroin-assisted treatment, it’s important to remember that much of the wider population is not there yet—even with more “vanilla” forms of harm reduction.

Given the severity of the current crisis, a discussion that helps debunk or at least bring clarity to myths like those below can only be valuable.

Myth 1: Maintenance medications for treatment of opioid addiction simply substitute one addiction with another.

Methadone, buprenorphine (Suboxone), and naltrexone (Vivitrol) are widely used to treat opioid addiction. Not only are they FDA-approved, but they have been around for decades, undergone rigorous efficacy testing, and are considered safe.

However, many are opposed to this form of treatment because of the belief that these medications simply replace one addiction with another. This thinking is partly due to unfortunate terms found in both the media and research literature, like “replacement therapy” or “substitution treatment.” Even the widely used term “medication-assisted treatment” sends the subtle message that these medications are not legitimate standalone interventions, but rather adjuncts to treatment—perhaps even a “crutch” for weak-willed patients.

The results of countless studies are unequivocal that these medications work—and a more appropriate term for them might simply be “medications.”

What’s important to note is that these medications do not always have to be paired with counseling to be effective—unlike the implication of the phrase “medication-assisted.” In fact, evidence in support of these medications is so strong and convincing that they are now considered the gold standard for treating opioid addiction by the World Health Organization and many other leading authorities.

Maintenance medications have characteristics unlike those of illicit opioids such as heroin or fentanyl. When prescribed properly, they have gradual onsets, diminish cravings, block the euphoric effects of other opioids, and do not intoxicate the user.

Most importantly, the evidence is clear that patients receiving medication for opioid addiction generally do better than those who do not. Studies show that such patients are more likely to secure employment, avoid arrest, reduce use of opioids, lower HIV seroconversion, and improve overall quality of life. And quite simply, these medications save lives—with buprenorphine, for example, cutting risk of overdose death by a staggering 50 percent.

To properly eliminate this myth, a rethinking of how success is defined in mainstream treatment is needed. Providers of all kinds should be aware that complete abstinence from all drugs is not always a prerequisite for treatment success, especially when it comes to prescribed medications. Treatment success can take many forms.

And although most patients stay on medication temporarily, those who choose to remain maintained for longer periods of time or indefinitely, because they are experiencing benefits, should also be considered success stories. The point is that just as with other chronic conditions, opioid addiction sometimes requires extended or lifelong use of medication.

Myth 2: Someone who takes medication for opioid addiction is not “in recovery.”

In connection with Myth 1, there is a vocal minority with the strongly held belief that recovery involving maintenance medications does not actually constitute true recovery. So, what exactly does it mean to be “in recovery?”

Strict adherents to the philosophy of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) argue that in order to achieve recovery, one must completely abstain from all mind-altering substances, in keeping with the principles found in “The Big Book.”

Obviously, “Bill W.” and “Dr. Bob,” AA’s founders in 1935, were not aware of the high number of casualties seen in today’s overdose crisis—nor were methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone available as treatment options back then. These new situations call for a re-evaluation of those original tenets.

Definitions vary, but recovery is today broadly recognized as being multi-dimensional. The Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel formulated a working definition of recovery as a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from alcohol and all other non-prescribed drugs, personal health and living with regard for those around you. A related but more inclusive definition, from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, states that recovery is “a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential.”

When considering modern conceptualizations of recovery, it’s clear that taking medication for addiction and being in recovery are not mutually exclusive. Medication has the benefit of fending off the intense drug cravings and uncomfortable withdrawal symptoms associated with opioids, thereby allowing individuals to live productive lives, focus on what really matters to them (family, relationships, job, service to others), and experience the benefits of lasting recovery.

Myth 3: Syringe exchange programs encourage and enable drug use by making it easier and safer.

The truth is that there is no compelling evidence of a connection between syringe exchange programs and increased drug use. Countless studies and evidence reviews have concluded the same thing. Studies also confirm that syringe exchange programs are safe, economical and effective at reducing rates of HIV and hepatitis C. In fact, the US Surgeon General’s official position on the issue is that a relationship between syringe exchange programs and increased drug use does not exist.

Syringe exchange programs are about far more than exchanging used needles with sterile ones. These programs often provide visitors with basic healthcare information, HIV testing, counseling, treatment referrals and a host of other services. Because of the wide range of service offerings at these facilities, the term “syringe service program” is increasingly being used by federal agencies and researchers, and is probably a more appropriate descriptor.

While we have seen a slight uptick in acceptance of these interventions recently in the US, as evidenced by a gradual increase in the overall number of syringe exchange programs nationwide, many still oppose them based on this longstanding myth. There is a poor appreciation for the role these programs play in providing people who inject drugs with opportunities for healthier futures.

The bottom line is that injection drug use is a reality and the presence of a syringe exchange program in a community will not cause people to use more drugs. With there only being about 200 legal syringe exchange programs nationwide, people get very little opportunity to visit these facilities for themselves. If they could, they would see that these programs provide a very important, non-judgmental point of contact for clients to access services that reduce the spread of infectious diseases.

Myth 4: Responding to overdose calls with naloxone is a waste of police resources.

Opponents of equipping police with naloxone (not to be confused with the opioid maintenance medication naltrexone) to respond to opioid overdose emergency calls often claim this falls outside the scope of law enforcement duties.

But while other emergency personnel also respond to such calls, police are often the first on the scene. As such, the ability for police to rapidly administrator naloxone—the opioid overdose antidote that has saved thousands of lives—is critical because administration must take place soon after opioid consumption to be effective. Minutes can sometimes be the difference between life and death.

Police are tasked with two of the most challenging and important responsibilities: 1. to instill law and order, and 2. to protect and serve their communities. The latter responsibility is becoming increasingly vital in light of the overdose crisis. We need an “all hands on deck” approach, and as part of that, the role of police must evolve. As opioid-involved overdoses continue to spiral out of control, police now have an obligation to respond to overdose calls and save the lives of people who use drugs. The increasing number of states enacting Good Samaritan or 911 Drug Immunity laws will only increase the importance of police officers as front-line responders.

If a police officer came across a teenager who appeared to be choking on her food, they would begin immediately administering the Heimlich maneuver. Even though such actions may not fall under the purview of law and order, any officer will tell you that they would proudly step up to protect and serve in such a scenario.

Why, then, would it be any different for someone who overdoses on drugs? Is their life any less worthy of saving than a choking child?

Besides saving lives, there are a number of additional advantages to police implementing naloxone overdose response programs. According to the US Attorney General’s Expert Panel on Law Enforcement and Naloxone, equipping officers with naloxone as part of a comprehensive overdose prevention initiative can improve community relations, enhance intelligence-gathering capabilities, and strengthen cross-agency communication. It creates a “united front” in the fight against overdose, and has the potential to reduce stigma.

Opponents also cite the economic burden. Naloxone is not free and kits represent an expense that was absent from most police operating budgets up until the last few years. However, just as public health departments of the 1980s and 1990s created new budget line items in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, so must today’s law enforcement in order to adapt to their communities’ changing needs.

Obtaining federal funds such as the Justice Assistance Grant Program and/or partnering with local health departments are also viable options for some police departments to help defray costs associated with overdose prevention initiatives. All agencies must make difficult budget decisions, but when people’s lives are on the line, an investment in naloxone has to take priority.

This Is No Time to Take an Ideological Stand

Drug overdose deaths continue to escalate each year, with no end in sight. The current crisis has now reached epidemic proportions, with about 192 people dying of a drug overdose every day. To put that in perspective, just imagine a typical commercial airliner going down in a crash and killing every passenger on board…every single day of the year.

Now is not the time to take a stand against life-saving harm reduction approaches on the grounds of ideology and myths.

It remains disappointing that despite mountains of supporting research and national lip-service to “evidence-based” approaches, harm reduction interventions still face such strong resistance. Clearly, there are those who still find these approaches scary and are made uncomfortable by them. But research says very loudly that they work, and more importantly, they save lives. If policymakers hope to turn the tide, a compassionate and science-driven harm reduction approach is essential.

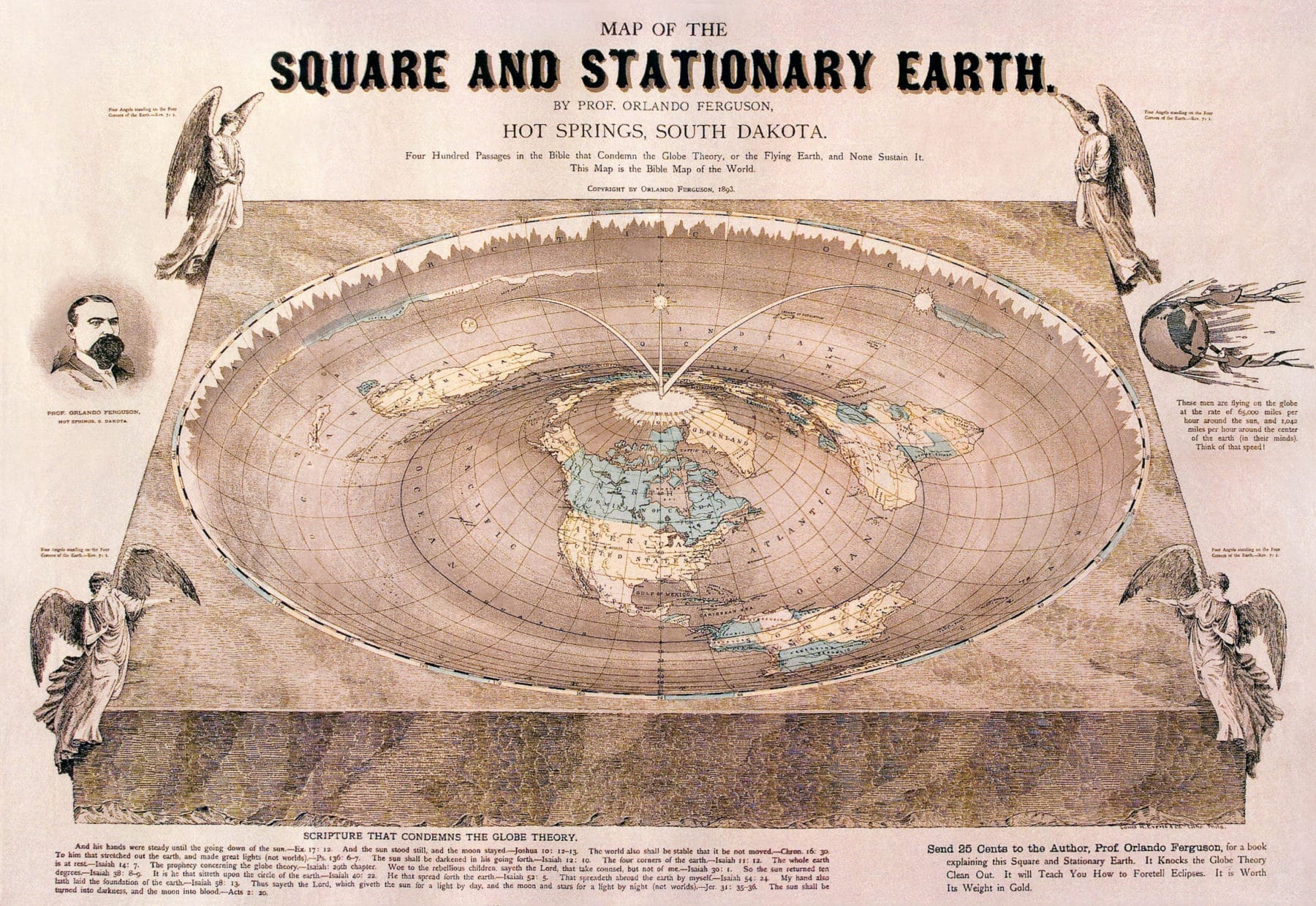

Flat earth image via Wikimedia Commons

Show Comments