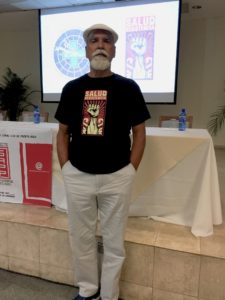

“They just took over the Nurses’ Residence at Lincoln Hospital,” says Walter Bosque, an acupuncturist and community organizer. His salt-and-pepper eyebrows are an archive.

I sat down with Bosque at the New York City Botanical Garden cafe on a brisk fall afternoon to discuss his involvement in the radical health activism of a fabled group in the history of grassroots organizing: the Young Lords.

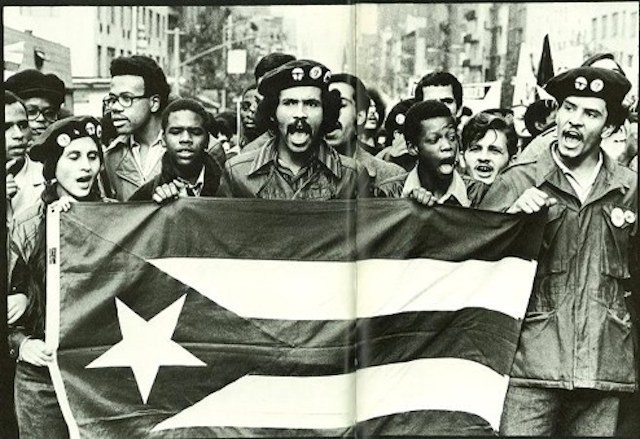

The Puerto Rican liberation organization–founded in Chicago in 1968 and pollinated to New York in 1969–kicked off its activism around issues like failing garbage collection services, infrastructure laced with lead paint, and lethal medical services. In ‘69 and ‘70, the Lords took direct action with the Black Panthers and other allies against derelict facilities and care deficits at Lincoln Hospital–known locally as the “Butcher Shop.” It was the only medical facility in the majority Black and Latinx South Bronx.

Bosque, a life-long Bronx resident with the vocal spunk to prove it, describes, between bites of chocolate croissant, a chance reunion with a childhood friend nearly 50 years ago–one that launched his life of political activism.

“I’m walking down the ol’ block … Number Six train, Longwood Avenue–with my first wife,” Bosque recalls of that scene at the end of 1970. “And I’m showing her where I lived: This is the school I went to, this used to be the barber shop I cut my hair at. So when I tell her about the barber shop, I see this Puerto Rican flag–this tremendous Puerto Rican flag that took up the whole storefront.”

Bosque strolled up. “Who do I run into? Mickey Melendez!” Having grown up together, Melendez and Bosque had once run a Bronx Latin jazz social club, the Plebeians Fraternity, before drifting apart. “I tell him that I am now in nursing school.”

Melendez had updates of his own.

Tensions and Occupations

With fellow Young Lords and allies, Melendez had taken part in a seizure of the Nurses’ Residence building at Lincoln Hospital on November 10, 1970. About 30 activists took over the mostly vacant sixth floor, according to the December 1970 issue of Palante, the Young Lords’ publication. They set up checkpoints and erected a barricade.

Lincoln Hospital had been “planning to institute a small drug program for some time; funds were anticipated from the City’s Addiction Services Agency (ASA).” But Lincoln’s track record overshadowed its promises. Heroin addiction was meanwhile widespread in the South Bronx, reported by The New York Times to affect 20,000 people there.

Having established overnight control of the sixth floor, the activists sought to “implement a drug program that would serve the community effectively and be run by the community.” At noon on November 11, “35 addicts along with workers from the hospital and community people” established what they called The People’s Program.

Later that day, cops in riot-gear broke through the barricade, arresting 15 people.

Tensions between hospital and community had simmered all year—in fact, the November action wasn’t the first Lords occupation of Lincoln in 1970. Funding cuts prompted a rally at St. Mary’s Park on June 27, after which police violence broke out. The Young Lords’ Bronx office was firebombed and eight community members “had their face beaten to a pulp,” according to the Soul City Times.

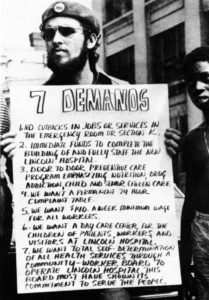

The next day, the Lords and community members set seven demands for Lincoln Hospital–and offered tuberculosis, lead-poisoning and iron-deficiency anemia tests to the underserved Mott Haven neighborhood.

Source: Michael Abramson, for “Palante,” via “Health PAC Bulletin” 1993

More uproar followed fatal mistreatment of 31-year-old Lincoln patient Carmen Rodriguez. What should have been a routine abortion became an avoidable death: Doctors failed to read her medical chart and administered drugs that triggered an allergic reaction, eventually killing her days later, on July 20. After the community got word, the Young Lords occupied part of Lincoln Hospital. Their action ended with members’ arrests.

In November, as the hospital hesitated over a heroin treatment program, the Young Lords again took matters into their own hands.

The People’s Program Launches

Perhaps surprisingly, after the November occupation was quelled, a negotiation occurred between the Young Lords and the hospital.

Astonishingly, within days, activists won “use of Lincoln’s anticipated ASA funds; the use of the old Nurse’s Auditorium in the Administration Building for the Detox Program; and a little office space in the Psychiatry Department.”

The People’s Program then launched, run entirely by volunteers for the first few months. Bosque joined after Melendez extended the invitation that day outside of the barbershop-turned-Lords-headquarters.

“I already worked with [Melendez] in the ‘60s and he’s a good friend…” Bosque tells me. “One more campaign can’t hurt. So I volunteered for the summer.” He chuckles. “Seven years later, I’m still at Lincoln Hospital.”

Methadone was not the only medicine used. The other was political education.

At first Bosque did intakes, drew blood and assisted doctors with patients’ medical histories. He saw himself as an interpreter for the doctors. “When people came to us, I knew who was ready to detox and who was not,” he says. “The secret was when they told me, ‘I’m tired. I can’t do this anymore.’ … The younger people who were still messing around, chasing the bag, hanging out, doing crazy shit, they were not ready. A lot of them came and recycled.”

Once admitted, the patients, all of whom were addicted to opioids, began a methadone detoxification regimen. “So we start with a 10-day detox cycle, first with 40mg of methadone, and then everyday we take away 5mg, until we get down to 5mg, and now they’re detoxed,” Bosque recites, with the clarity of an active practitioner–even though this was half a century ago.

But methadone was not the only medicine used. The other was political education. “We used to tell ‘em, when they got off the drugs and they didn’t want to get back on drugs: If you detox and go back to the block, the pusher man is going to be at the corner. And sooner or later you’re going to fall,” Bosque recounts.

The ubiquity of heroin in South Bronx social life presented a challenge. To counter this, The People’s Program politicized the origins of the heroin trade, drawing the “connection between capitalism, dope and genocide.”

Each patient received a copy of “The Opium Trail: Heroin and Imperialism,” a pamphlet written by the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars that advocates political revolution as “an alternative explanation and another focus for anger, as well as collective support and some sense of direction.” The pamphlet urges, “The movement can be the best form of therapy.”

Bosque and his colleagues didn’t just encourage clients’ recognition of social determinants; they offered means to act. “We knew that oppression and resistance went hand-in-hand,” he says. “And so we recruited hundreds of people and we started political prisoners’ funds, from the South Bronx to the Lower East Side. We filled the courthouses.”

The Program’s patients participated in “a succession of sit‐ins, sit‐downs and occupations,” reported The New York Times. “They have organized rent strikes and picket lines of people seeking jobs at construction sites. They have joined the demonstrations of others, including the street protests of the gypsy‐cab drivers.”

“There was a movement,” Bosque says proudly. “And it all started from the civil rights movement, the Black movement, and the movement for the independence of Puerto Rico. So this became a coalition. It was the extended family.”

Bosque considered the rules around methadone administration to be a form of state oppression.

The collective was wary of the mainstream-medical heroin detox drug: methadone. Bluntly, Bosque explains: “The medical name for methadone was ‘Adolphine,’ after the Great Oppressor, Adolf Hitler, who ordered scientists to find a synthetic alternative to morphine.” This was a political non-starter for Bosque. (It should be noted, however, that long-term methadone use cuts mortality for people with opioid use disorders by half or more.)

Bosque also recalls acute practical issues: “Clients would take a weekend dosage home and keep it in the refrigerator. But the problem was that we would mix the methadone with Tang to color the methadone, since it is a clear liquid. The client’s kids would wake up in the middle of the night and think it was orange juice–and drink it! We had a lot of problems with overdoses for children.”

It wasn’t just kids. “Clients would buy methadone on the street from somebody else who was selling their [whole] weekend dosage, and they didn’t realize that 20 mg would kill you.”

Bosque also considered the rules around methadone administration to be a form of state oppression: “Once on methadone, the client really can’t travel. Let’s say they want to go to Puerto Rico or to North Carolina to visit their grandma. Doctors won’t give them the methadone to go. Methadone is a liquid handcuff.”

For these reasons, the Young Lords sought an alternative.

A Journey Into Acupuncture

At a Program collective meeting, Program worker Mutulu Shakur read aloud an article about a Bangkok doctor who used acupuncture as an analgesic–a common practice–on a patient who happened to use opium. The patient reported that since receiving acupuncture treatments, he no longer wished to smoke opium.

“Maybe this is what we need!” Bosque recalls exclaiming that day. The People’s Program promptly hired two acupuncturists to perform auriculotherapy, the form of acupuncture that focuses on needling the ear.

As the mediator between acupuncturist and client, Bosque was tasked with demystifying an unfamiliar needle. “We had to convince the clients that it’s okay to get needled, that there are no drugs in the needle. Because these addicted people had been shooting up for half of their lives, and now we are going to hit ‘em with a needle. We had to make clear that … you’re not really going to get high, but you’re going to get very relaxed, and it’s going to help you get detoxed.”

Still, limiting the role of Young Lords workers to mediation did not quite fit with the group’s do-it-yourself ethos. “While we were helping the acupuncturists and watching them do it,” Bosque explains, excitedly, “we came to the realization that we can do this ourselves. We really don’t need the acupuncturists!”

“So we went down to Chinatown and bought some boxes of acupuncture needles. Back then we used to say, ‘Each one, teach one.’ We started teaching each other. And that’s how deep the acupuncture clinic that formed at The People’s Program was in creating itself.”

What Bosque describes so rapidly and casually would later become formalized as the National Acupuncture Detoxification Association Protocol.

Listening to Bosque, the entrepreneurial, autodidactic spirit of the Program is palpable. “So now we started doing the auricular therapy,” Bosque continues, knuckling the patio table. “We started with one needle attached to an electric stimulator, which is what they were using as anesthesia in China. But we realized that after a while, a little callus formed … we needed to use more than one needle. So we stopped using the machine and we started using three needles. And then three needles became five needles.”

What Bosque describes so rapidly and casually would later become formalized as the National Acupuncture Detoxification Association Protocol. Bosque and other People’s Program members experimented with and refined this technique that, according to him, “was a viable medical modality that was safe, cost-effective and it worked!”

Research results regarding the efficacy of the protocol are mixed. Some studies around general acupuncture for opioid addiction are positive; others indicate that auricular acupuncture positively affects detox when paired with other treatments. A report from the US Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, however, finds no conclusive evidence to support the efficacy of acupuncture detoxification. And a literature review suggests that “acudetox” is flat-out not effective.

Efficacy and evidence are always vital. But in this history, they are not the only point. The Program’s use of acupuncture inspired, and can now crucially inform, the ways that health activists organize—by expropriating medical knowledge for community use and building networks of care, without the approval of institutional power. In a time when laws continue to impede responses to our overdose crisis, that has never been more relevant.

The dissident character of the Program meant officially implementing acupuncture detoxification was tricky. In New York state, practicing acupuncture was restricted to doctors–or at least, to those under their supervision, which was the path the Program took.

In typical lemons-into-lemonade style, they found a chance to use their skills outside of the clinic.

Bosque and three other collective members–Mutulu Shakur, Richard Delaney and Rick Bird–went on to become certified acupuncturists in Quebec and California, after training in Montreal during the mid-’70s. Even then, they could not legally practice in New York.

But in typical lemons-into-lemonade style, they found a chance to use their skills outside of the clinic. The Lincoln Acupuncture School launched in the late ‘70s, training students in what Bosque and his comrades had learned in Montreal and California. Many of the students–including Mark Seem, founder of the Tri-State College of Acupuncture–would go on to shape the landscape of acupuncture in New York City today.

A Violent End and a Vital Legacy

Tension continued to ripple between the Program and New York City government. An integral doctor of The People’s Program, Dr. Richard Taft, was mysteriously found dead in a closet in the clinic amidst suspicious violent threats to the Program. The Health and Hospital Corporation attempted–unsuccessfully, after activists’ direct action–to cut Program funds in 1975.

In 1978, Mayor Ed Koch dispatched “riot‐equipped police” to evict The People’s Program from Lincoln Hospital, a final blow reminiscent of the November 1970 police-raid on the occupation that birthed The Program.

Members accused Koch of shutting down the Program because of his disdain for the Young Lords’ political agenda. This seems to be accurate, given Koch’s response: “Hospitals are for sick people, not for thugs.”

After the eviction, a tamed detox program continued at Lincoln–one that Bosque distinguishes from its politically radical forerunner. Bosque says that he and his colleagues saw Koch’s attack coming. He shrugs, “We were a threat to the establishment.”

After nearly three hours, Bosque and I still sit on the back patio of the cafe. He’s retired now, but his days remain full, after more than 50 years of activism and counting.

He volunteers with the Harlem-based New York Harm Reduction Educators and continues practicing acupuncture with the disaster-relief organization Acupuncturists Without Borders in Puerto Rico. He also works with Proyecto Salud y Acupuntura para el Pueblo (Health and Acupuncture for the People) to provide free auricular acupuncture to people in both locations. Bosque is also collaborating on two documentaries, and writing an autobiography set to be published in 2019.

“Back in those days, we were revolutionary scientists,” he enthuses, “and we were willing to learn whatever we needed to learn to provide the people with what they needed.”

It’s time for Bosque to get going. His smile in the fading light gleams with reverence for the work that he and his comrades pioneered–strategies we may now need more than ever.

Main image: A Young Lords March in the Early 1970s. Credit: Michael Abramson via Village Voice