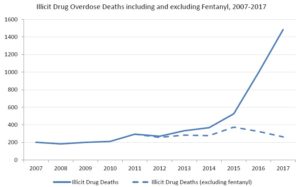

The crisis of opioid-related deaths extends throughout North America. Similar to cities across the United States, Vancouver, Canada, is flooded with illicit fentanyl. According to the British Columbia Coroners Service, the synthetic opioid was associated with 85 percent of overdose deaths in 2018, up from 15 percent just five years earlier.

Drug testing conducted at various safer consumption spaces (SCS) confirms that fentanyl has all but completely replaced heroin. Worse, an even more toxic opioid, carfentanil, arrived in the winter of 2016. Overdose deaths in BC increased from 333 in 2013 to 1,489 in 2018. This February 2019 graphic from the BC Coroners Service illustrates the extent to which fentanyl-involvement has come to dominate overdose deaths:

In response, the province has invested heavily in harm reduction. Naloxone is available free of charge and without a prescription. In addition, there are now at least 15 sanctioned SCS in BC, where people can bring drugs to inject them under the supervision of staff trained in overdose response. Authorities attribute some success to these programs. BC’s chief coroner, Lisa Lapointe, has estimated that without harm reduction, BC would see close to triple its current number of fatal overdoses. However, while the stats have plateaued, they have not declined.

Now a group of researchers working with drug users in Vancouver has proposed a radical additional response. They want to make pharmaceutical-grade heroin available as a regulated, relatively safe alternative to illicit fentanyl sold on the streets.

“This model is inspired by cannabis compassion clubs and buyers clubs, both of which emerged in the 1980s and 1990s in response to the AIDS epidemic,” reads a white paper published February 21 by the BC Centre on Substance Use (BCCSU).

The prominent Vancouver research organization—which operates with strong ties to the BC government—calls the document a “blueprint for heroin regulation”.

“The compassion or buyers club would function as a cooperative (or ‘co-op’), as an autonomous and democratic enterprise owned and operated by its members,” the report begins.

“A member-driven purchasing cooperative is an arrangement among businesses or individuals whereby members agree to aggregate their demand in order to purchase a certain product at a lower price from a supplier,” it continues. “By aggregating their purchase orders and relevant resources, members are able to take advantage of volume discounts, price protection, shared storage and distribution facilities and costs, and other economies of scale to reduce their overall purchasing costs.”

How the Clubs Would Work

If you’ve seen the award-winning 2013 film Dallas Buyers Club, you have a rough idea of how a “heroin compassion club” might operate. The BCCSU’s report paints a more structured picture, however. To start, individuals addicted to opioids would receive a medical evaluation required for membership. Once accepted into the club, they would still have to pay for the heroin they used, but could do so with many advantages over purchasing drugs in the illicit market.

Members would not receive an unknown substance that likely contains fentanyl. Instead, they would have access to pure prescription heroin (diacetylmorphine) or, if the club chooses, a mixture of powdered heroin plus a known cutting agent, such as caffeine.

The drug would come from a legal producer in Europe. (The report doesn’t name potential partners, but a likely candidate is DiaMo Narcotics in Switzerland, which already has a presence in Canada via a Toronto-based distributor named Almat Pharmachem.) Then each compassion club member could inject the drug at a designated location—it would make sense to integrate the clubs into existing SCS—or take a small supply of the drug off-site for consumption at home.

The BCCSU recommends keeping barriers to joining these clubs low, arguing against any sort of medicalized model that would require regular meetings with health-care professionals. The report also suggests that each compassion club include complimentary services such as overdose-response training, naloxone distribution, and optional connections to detox, rehab and other treatment options.

Working Within an Existing Legal Framework

Dr. Evan Wood is the BCCSU’s executive director and a co-author of the report. He told Filter that his team’s goals were to find a way to make a regulated supply of heroin available as a relatively safe alternative to street fentanyl, and to do so without requiring changes to existing Canadian laws that forbid trafficking and possession of illicit narcotics.

They found two possible answers to this challenge, Wood continued.

The first is what’s known in Canada as a “Section 56 exemption.” Section 56 of Canada’s Controlled Drugs and Substances Act allows the federal government to exempt “any person or class of persons” from criminal penalties related to drugs if “the exemption is necessary for a medical or scientific purpose or is otherwise in the public interest.” (The same exemption has allowed North America’s first legal SCS, Insite, to operate without breaking the law since it opened in Vancouver in 2003.)

The second legal option is Canada’s Drugs for Urgent Public Health Need (UPHN) program. It allows health officials to request to import a drug that is not available through regular channels if there is an “urgent public health need for the immediate use of the drug”.

Wood said that either of these options could be combined with a research component to allow a heroin compassion club to operate without breaking the law.

“An evaluation creates an opportunity for British Columbia to go ahead with something like this without requiring a federal health minister to stand up and say, ‘We’re legalizing heroin’,” Wood said. “This is an opportunity to do something like this…with the federal government essentially just staying out of the way.”

Most Heroin Users Don’t Want Fentanyl

With supply theoretically covered, another question the BCCSU sought to answer concerns the demand side of the market. Would potential members of a buyers club want heroin?

In a separate interview, Erica Thomson, another co-author of the report, told Filter there’s a perception that people who use drugs always seek the most potent substance available, which, with opioids, means fentanyl or carfentanil. But Thompson maintains that is a bit of a myth.

She explained that in her work as a peer coordinator for a regional health authority, she speaks every day with people who use drugs. Most have consistently told her that the only reason they are using fentanyl is because it is the only opioid dealers are selling.

“This is the piece that worked for me. That comfort.”

Thomson said that anecdotally, there are key differences between fentanyl and heroin that have left many people addicted to opioids struggling with pain. Not physical pain or symptoms of withdrawal—fentanyl takes care of those issues just as well as heroin, Thomson said. Where fentanyl falls short is is in situations where people are using opioids to self-medicate past trauma or emotional pain.

“I once had a woman weeping when they went back to old-school heroin,” Thomson recounted. “There were tears in her eyes. She said, ‘This is what I missed. This is the piece that worked for me. That comfort.’”

Several longtime drug users interviewed for this story similarly said that fentanyl lacks the “warmth” or “hug” that’s often associated with heroin. Kevin Yake is president of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), a grassroots advocacy organization established in 1997 and comprised entirely of people who use drugs. He said that fentanyl is generally not a drug of choice in Vancouver, and is only popular because there are so few alternatives available. “Even if they’re doing fentanyl, a lot of people don’t like it,” he emphasized.

The BCCSU has numbers that support such anecdotal reports. It recently surveyed 650 people in Vancouver who regularly use opioids, and found that 80 percent said they preferred heroin, whereas only 16 percent said their preference was fentanyl.

Unique Potential

Prescription heroin has already been available in Vancouver for some time, but only on a very limited basis. (It has also been successfully deployed in several other countries, most famously Switzerland, where it was introduced in the 1990s.) In 2014, an academic trial called SALOME transitioned into a regular opioid-substitution program that today sees roughly 130 patients receive either diacetylmorphine (in most cases), injectable hydromorphone, or slow-release oral morphine.

Called Crosstown Clinic, this program is a highly medicalized model that requires a standalone facility staffed by a full-time doctor plus an entire team of nurses. That means it is expensive to operate (though, as studies have shown, it still produces net savings for the government, thanks to lowered police and emergency-response costs that patients no longer incur once they receive opioids via the healthcare system).

In contrast, buyers clubs could expand across the country with minimal costs and relative ease, Woods said. “We believe that a cooperative model where people purchase heroin could essentially be self-sustaining without any ongoing taxpayer investment.”

“A cooperative could undermine the illegal market wherever it is set up.”

Finally, the report describes how the creation of drug-user cop-ops could gradually supplant much of the illicit market, therefore minimizing violence associated with organized crime.

“Fentanyl adulteration in the illicit drug supply is a predictable unintended consequence of drug prohibition,” it reads, reflecting the so-called “Iron Law of Prohibition.” “The same forces that pushed the market away from relatively bulky opium towards heroin, a more concentrated opioid that was easier to transport clandestinely, have continued to push the opioid market to increasingly potent synthetic opioids, including a range of fentanyl analogues.”

The document concludes: “A cooperative could undermine the illegal market wherever it is set up.”

Yake cautioned that a heroin compassion club would not solve BC’s fentanyl crisis overnight, but added that there is no doubt it would save lives. Even if it’s only a small number at first, Yake argued that makes the idea worth serious consideration.

“This fentanyl thing, how do you stop it? I don’t know,” Yake said. “But I think I do know how to prevent deaths. That’s by having other drugs available. Something that you know where it comes from, you know what’s in it.”

Image via the British Colombia Centre on Substance Use