In the two weeks since the first coronavirus cases were confirmed in New York City, the harm reduction landscape here has been rewritten. After two or three days of operating the Lower East Side Harm Reduction Center by letting one participant into the syringe exchange at a time, on March 16 we shifted to a somewhat dystopian system of keeping everyone outside and communicating with them over the intercom. People’s codes and supply requests blare over the speaker, usually after several failed attempts to synchronize who’s holding down the buzzer. Then, wearing gloves, we hand them their supplies at the door.

The team of volunteers, peer workers and staff who keep the exchange running has been whittled down to a skeleton crew. Three of us disinfect a table and move it into the middle of the drop-in center, which is normally a pretty lively place but is now closed indefinitely.

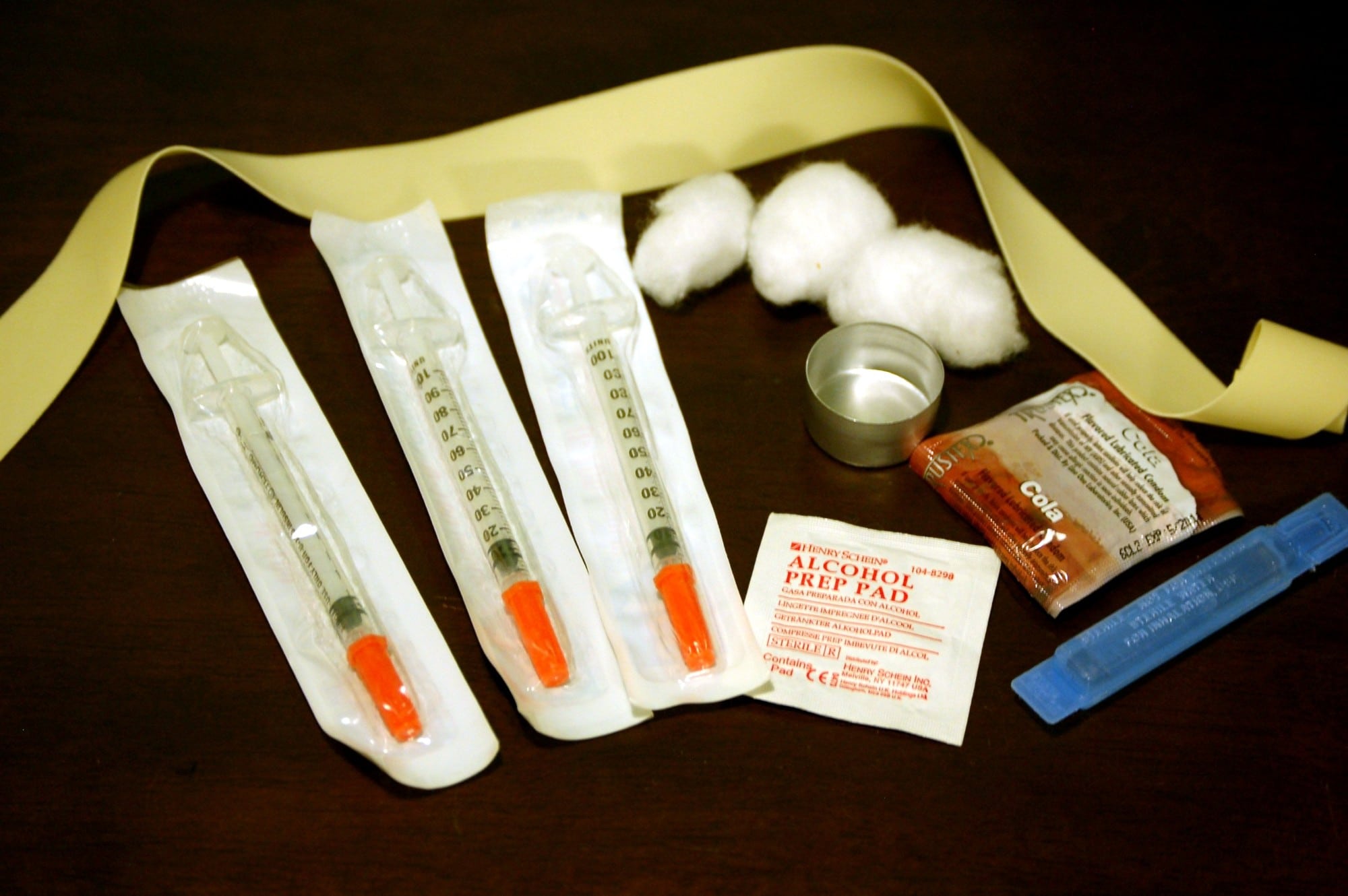

In the gaps between intercom buzzes, we pack single-serving kits with needles or pipes, as well as other supplies that we normally have available up front for participants to add to their bags themselves. Everyone’s needs are different, so deciding what makes it into the kits is a little arbitrary. We go with one one-shot cooker, one baggie of cottons (ours always contain three), one baggie of gauze, four distilled waters, four alcohol pads, four antiseptic wipes and four Band-Aids.

“It feels like we’re going to war.”

We talk about people we’re worried for and wonder aloud about changes that might be coming next, but mostly we work in silence until someone knocks or hits the intercom. We wear gloves and keep the lights low, partly to help communicate that the drop-in center isn’t open and partly because it just feels fitting. Another volunteer messages me that she’s self-quarantining due to exposure. Everything smells like we’re inside a swimming pool. Our manager of Harm Reduction Services tells me that even at the height of New York’s overdose crisis back in 2015-2016, nothing ever forced the drop-in center to close. “It feels like we’re going to war.”

The situation is evolving so quickly and chaotically that it’s hard to know whose information is correct from one minute to the next. Interviews and crowdsourced recommendations from a dozen or so harm reductionists and organizations around the country, however, have yielded at least a few points on which there appears to be wide consensus.

Here’s what we know so far about how harm reductionists are keeping people who use drugs as safe as possible during the pandemic.

Awareness Varies Widely, But We Can Help Fill the Gaps

“A lot of our participants didn’t even realize there were any cases in Iowa,” said Sarah Ziegenhorn, founder of the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition. “I was talking to a client today who thought coronavirus was made up; he didn’t know it was real.” Zeigenhorn’s organization serves around 27 of Iowa’s 99 counties through mobile outreach and has a storefront in Cedar Rapids. “I also see some who just got out of jail and they’re trying to bail their friends out of jail, because they recognize that the jail is a really high-risk place to be right now.”

Multiple NYC participants have told me they think the coronavirus is a conspiracy; many more believe that, at the very least, it’s being blown out of proportion. Misconceptions are understandable given how little reason people who use drugs have to trust our government or healthcare systems. Marginalized people who use drugs might be acutely aware of the virus, but know considerably less about how to avoid it.

The Harm Reduction Coalition has put out a guide for safer drug use during the pandemic, as well as a separate one for harm reduction operations. The New York City Department of Health told Filter that those are the guidelines it’s sent out to the city’s 14 syringe service programs. In order to encourage sharing of some of the key takeaways among syringe program participants, I have also summarized the first of these communications at the bottom of this article.

Encouraging People to Stock Up and Avoid Sharing

At the Lower East Side Harm Reduction Center, as at a lot of harm reduction programs, we generally try not to push anything on participants that they themselves didn’t ask for. But since the pandemic landed, we’ve been suggesting that people stock up on as much of whatever they need as they can: extra syringes, pipes and stems, alcohol pads, sterile water—everything.

If people who are on methadone use a clinic that will let them take home additional doses, they’re advised to stock up on as much as they can there, too.

I’ve been putting hotel soaps in everyone’s bags whether they ask for it or not. I would throw in hand sanitizer, but we don’t have any.

“I’m trying to get our health department to buy smoking kits, justifying it as an emergency.”

While sharing works is never advisable, the pandemic adds an extra layer of risk. Syringes, straws, pipes, stems and other means of using drugs could carry the virus from person to person if shared. Harm reductionists like Ziegenhorn and Alexis Pleus, founder and executive director of the nonprofit advocacy group Truth Pharm, both suggest emphasizing to participants that this is an especially important time to avoid sharing works, and for people who inject drugs to use a new syringe each time.

“I’m trying to talk with people a lot more about safe smoking, because smoking stimulants is so common here,” Ziegenhorn said. “It always has been. A lot of people shoot and smoke, and we don’t give safer smoking kits. I’m trying to get our health department to buy smoking kits, justifying it as an emergency.”

Preparing for Widespread Withdrawal

“I think our drug supply is about to go to hell in a handbasket,” said Devin Reaves, co-founder and executive director of the Pennsylvania Harm Reduction Coalition. “We need to be making sure that we can remove as many barriers as possible to access medications for opioid use disorder … methadone and buprenorphine and other quote-unquote ‘treatment.’”

Ziegenhorn also cited her biggest concern as people who are opioid-dependent losing access to their supply; Iowa’s drug supply is heavily contingent on daily road deliveries from Chicago. “I’m worried that it’s gonna result in a lot of people who are very, very sick,” she said. “Basically what I’m trying to do right now is … connect people with buprenorphine as fast as possible.”

Staff of the Alliance for Positive Change in NYC, which oversees the Lower East Side Harm Reduction Center, are preparing for the same. There’s also concern that the disruptions to the usual supply chain could lead to the influx of a lot more heroin adulterated with fentanyl.

Heightened Risk of Overdose

Telling people who use drugs to socially isolate is in direct opposition to the advice folks in the harm reduction community know saves lives: Use with friends; don’t use alone. Almost everyone interviewed for this piece immediately cited concern about the pandemic significantly spiking the risk of opioid-involved overdose. Public health instructions to avoid human contact also coincide with the removal of a lot of community safety nets like drop-in centers and naloxone distribution.

“And it seems like so many people are feeling this really intense sense of anxiety, too,” Ziegenhorn said. “That can push people to want to use more.”

Beyond the implications of increased use combined with decreased care, people who use opioids are also at greater risk right now because COVID-19 is a respiratory condition. The combination can heighten both the risk of overdose and the risk of deteriorating more rapidly following exposure to the virus.

“Anything that may produce chronic lung injury may increase risk of experiencing severe disease,” Dr. Leandro Mena, founding chair of the University of Mississippi’s Population Health Science Program, tolld Filter. “Many of [these] drugs (inhaled or injected) deposit substances in the lungs that can generate fibrosis, which in turn will make them more susceptible.” People who use opioids should consider themselves one of the at-risk populations for COVID-19.

People who smoke drugs could also have a harder time inhaling; where possible, harm reductionists might suggest that they shift to snorting.

Some People Living With HIV Could Also Be at Increased Risk

Risk of developing severe symptoms from COVID-19 is higher for anyone with underlying chronic disease. “For people who live with HIV, anyone who is not suppressed/off medications probably has a higher risk of morbidity because of the relative weaker immune system compared to [what] it would be if they are suppressed or on ART,” said Mena, who is one of the country’s leading HIV experts.

Pleus noted that people with hepatitis might be at greater risk, too. Hep B and C can lead to liver disease, which would make someone more susceptible to COVID-19.

Pivoting From Drop-in to Outreach

No one could say that harm reduction communities haven’t faced massive public health emergencies before, but this is the first one that’s forced programs to close. Just as we have been in New York City, Ziegenhorn said that in Iowa they’re asking participants to wait out front rather than letting anyone hang out inside. Reaves said that most of Pennsylvania’s programs are closing their drop-in centers, too.

“But for a lot of people who are delivering harm reduction services, staying home doesn’t feel like an option,” Reaves said. “Volunteers are gonna go out regardless, because they have people that they care for, and oftentimes people that run syringe service programs are the only people who treat them with humanity and dignity and give them these lifesaving supplies like naloxone. So they’re not gonna stop.”

Everyone in harm reduction is looking for ways to balance a new kind of social responsibility with an older one—to self-isolate and restrict our own movements as much as possible while also doing what the harm reduction community has always done: meeting people where they’re at.

If people are not coming to drop-in centers, and if they’re discouraged by the restricted hours and services at syringe service programs, then we need to be getting more creative in the ways we conduct outreach.

The North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition has suspended fixed-site exchanges but is continuing mobile deliveries, handing out naloxone and COVID-19 informational flyers with everything else and keeping people six feet apart during group exchanges.

Harm reduction is used to adversity.

Providers who have access to mobile clinic vans can be figuring out which routes and services can be expanded. Those who have phone numbers for participants preparing to use alone can ask if they’d like someone to Facetime, or just to stay on the line in case something goes wrong. Those doing peer-delivered syringe exchanges can try to set up outside meeting points instead of going into people’s homes. Those doing backpack deliveries might consider wearing gloves, and setting supplies down in front of people rather than handing off anything directly; no handshakes or hugs.

Harm reduction is used to adversity. Hopefully we can do a good enough job of conveying to people that social distancing is simply due to an extraordinary set of circumstances, which are serious but still temporary, and not because we don’t care. That, at least, should be something we know how to do.

Staying Safe During the Pandemic (Based on Harm Reduction Coalition Materials)

* Wash your hands with soap for at least 20 seconds, as often as you can

* Hand sanitizer with at least 60 percent alcohol is the next best option

* Try to stay at least six feet away from other people

* Cough into your elbow

* Try to not touch your face

* Don’t shake hands—elbow bump or fist bump

* Stock up on clean works as much as you can

* Don’t share your works—you can pass on the virus in this way

* Be prepared for your supply to be interrupted—if you use opioids, consider accessing methadone or buprenorphine/Suboxone for the next few weeks at least

* Be aware that you can spread the virus to other people even if you do not feel sick

* Symptoms include fever, shortness of breath, coughing and fatigue

* If you feel sick, try to stay put and monitor your symptoms. Only go to an ER if you feel very sick; this is so hospitals don’t get overwhelmed with everyone coming in at once

* COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, is a respiratory disease, so it puts people who use opioids at greater risk of overdose

* Most people who contract the coronavirus will recover, but people who are over 60 and/or have health conditions like heart disease, diabetes, lung disease or cancer are at greater risk

We know this is hard. The virus is expected to keep spreading for months, but it won’t be like this forever. For now, it’s important to take as many precautions as possible to keep yourself and people around you safe. The Lower East Side Harm Reduction Center’s syringe exchange program, like many others, will remain open.

Photo of the contents of a syringe exchange kit by Todd Huffman via Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons 2.0