For the first time in six years, in 2025 the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles allowed more people to go home than they did the year before. Parole was granted to 5,588 prisoners—145 more than in 2024, and 14,776 fewer than were eligible.

The numbers are available in the Board’s latest annual report, released earlier in January. After the requisite glossy bios reminding us that there’s a new addition to the Board and that all five members still have backgrounds in law enforcement, we eventually learn that 20,364 people were eligible for parole in 2025. Not a good reflection on GDC’s rehabilitative programming that the Board saw fit to release so few.

Nothing about this is decarceration. Per Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) annual reports the prison population grew by about 684 people in 2025. To those of us inside GDC’s prisons these are not numbers, but human beings sleeping on floors and in mop closets and in shower stalls.

Parole is the mechanism that could fix this, or at least provide substantial relief. The Board constantly references the imperative of public safety and yet, as suicides and homicides continue to rise inside GDC, not once do these reports ever reference the safety of the incarcerated population.

Proponents of mass incarceration characterize parole as if it opens the floodgates for people who are somehow cheating the system. But in addition to the fact that the system considered them parole-eligible, the people being released were about to be released anyway.

An analysis by Georgia Prisoners’ Speak found that in 2024, nearly one in four people granted parole were within six months of their release date. To be sure, those months make a big difference to prisoners and their families, but the Board gets to tout the statistic that 73 percent of Georgia parolees were “successful” in 2025, comparing favorably to the national average of 60 percent. Lifers who do make parole have exceptionally low recidivism rates, but no one seems to consider this reason to release more of them.

The Georgia Prisoners’ Speak analysis also indicates that almost all the lifers currently out on parole have been out for a very long time—estimating that the state has only 17 lifers out on parole whose convictions likely took place within the past 20 years. Per the new annual report, in 2025 the Board considered 2,277 parole-eligible lifers for release, and released 123 of them.

Nearly 200,000 people in the United States are serving life sentences, and nearly half of those are eligible for parole. But parole is essentially a bygone era.

More than a dozen states don’t even pretend to offer parole. Those that do are steadily pulling it out of reach of those of us with life sentences.

In the early 1990s when I began my sentence, lifers were eligible for parole after seven years. By the time I’d served seven years the bar had been raised to 14 years, and by the time I’d served 14 years it had been raised to 30 years.

Since the 1970s, Colorado has progressively raised lifers’ parole eligibility from 10 years to 20 years to 40 years to effectively removing parole for life sentences entirely. Louisiana has charted almost the same trajectory. Tennessee requires a minimum of 51 years served before parole—the longest of any state.

Meanwhile, each state’s parole or other executive clemency processes are overseen by a group not too dissimilar from Georgia’s Parole Board: a small handful of retired sheriffs and district attorneys who aren’t beholden to much if any transparency about their decisionmaking.

It should not be lost in all this that parole is hardly a mercy. It is dragging vulnerable people to the brink of human endurance and then kicking them back out into an unfamiliar world with $35, and often a one-way bus ticket back to prison intake.

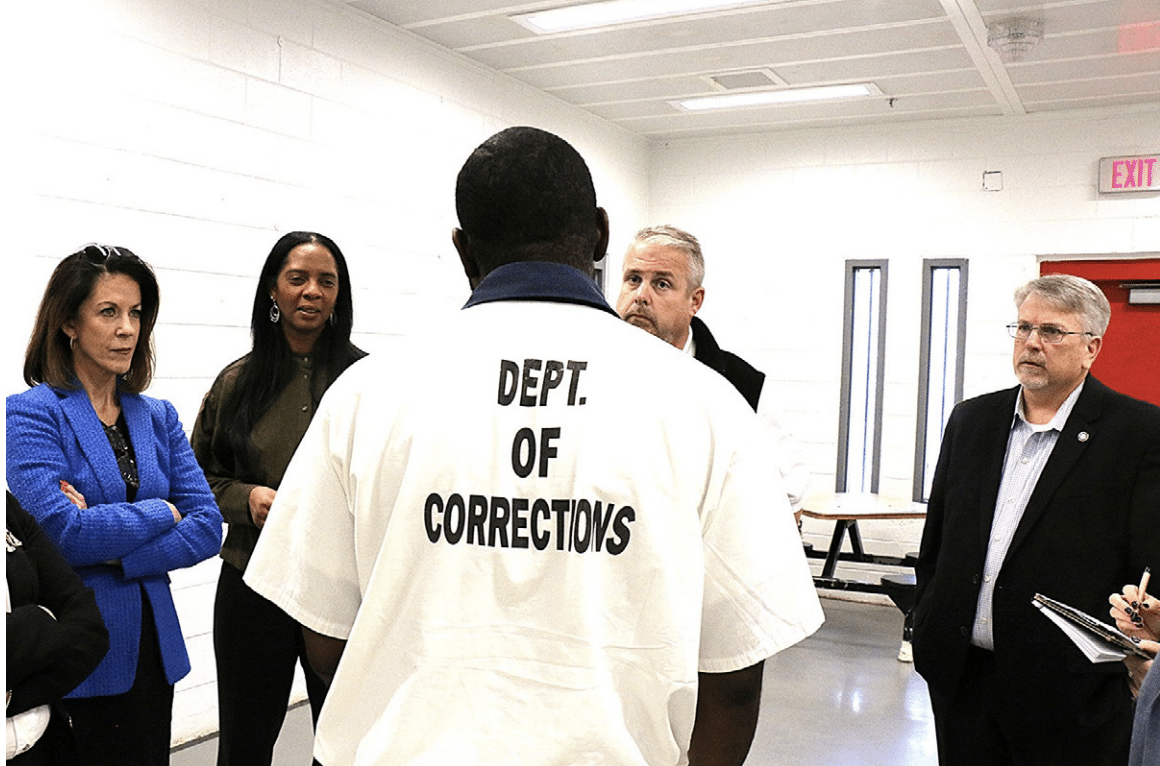

Top image (cropped) via Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles. Inset graphic via Filter.