It’s a scorching July day in British Columbia, at Bass Coast festival, and there is no line outside the drug checking tent. I decide to bring along a sample of my 2C-B, a psychedelic stimulant also known as “tripstasy.”

Inside, two chemists examine the powder through a microscope and advise me not to take all of the dose at once, since it is entirely pure. Naturally, I take heed.

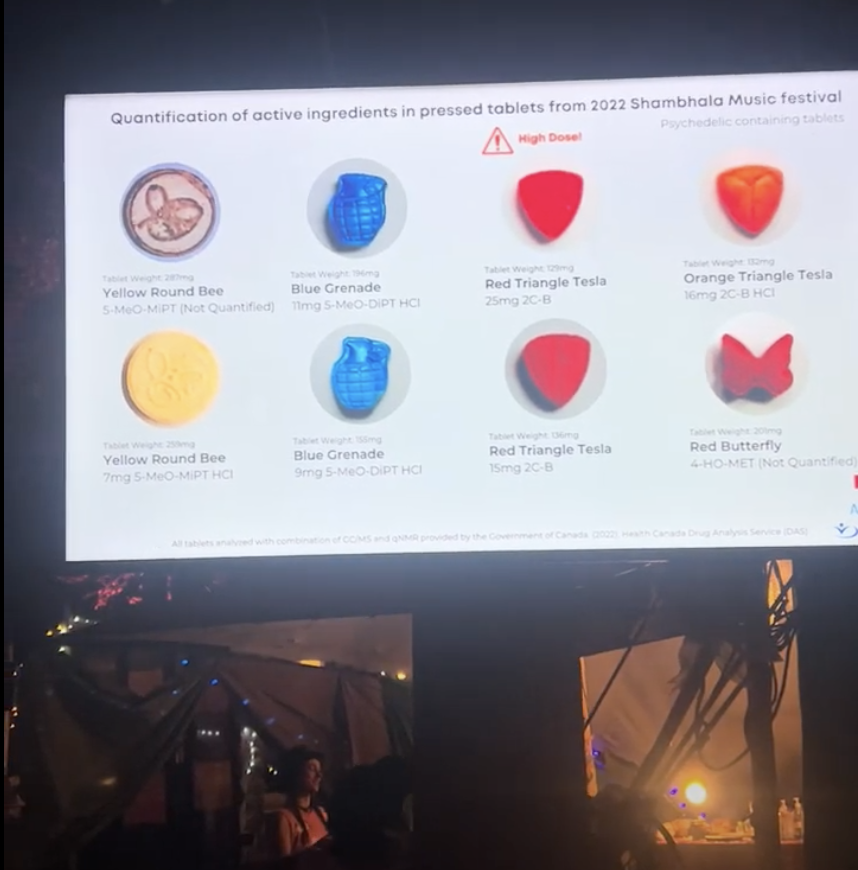

The scene at the mobile drug checking facility seems futuristic, foreshadowing the common-sense drug approaches of tomorrow. A large screen outside of the prominently placed gazebo warns ravers about high-potency or adulterated drugs which have recently been in local circulation. A chart helpfully advertises which drugs are risky to use in combination with each other. A sign impresses the importance of set, setting and dose, and invites people to ask questions.

It’s soon easy to forget that compared to the norm in many places, this is a radical offering. Few other countries permit such services at festivals. In the United States, testing is only officially available at a few smaller festivals where promoters have decided to take legal risks. Despite a number of recent drug-related deaths, the larger festivals have yet to get on board.

This reluctance is substantially a consequence of the 2002 Reducing Americans’ Vulnerability to Ecstasy (RAVE) Act, a federal law introduced by then-Senator Joe Biden, which makes rave organizers criminally liable for drug use at their events. The law discourages promoters from providing harm reduction services, for fear of then being held liable for any harms related to participants’ use.

“By spending a few minutes getting your drugs tested, we can help you engineer a really great festival.”

Bass Coast, which primarily showcases underground DJs, began testing drugs in 2018 following consultations with local authorities. The move came after BC was rocked by drug-related deaths at Shambhala festival in Nelson, in 2012; at Boonstock festival in Penticton, in 2014; and at the Center of Gravity festival in Kelowna, in 2018.

Shambhala, which in 2024 hosted 20,000 people on its privately-owned land, initially offered unauthorized and unadvertised testing from 2004, delivered by the pioneering harm reduction organization ANKORS. This went public in 2015, and was authorized not long after.

But some other festivals in BC and elsewhere in Canada—despite the successes of groups like GRIP, who test at events in the east—have not been able to secure permissions locally, according to Bass Coast Harm Reduction Manager Stacey Forrester. That’s even though the BC government previously wrote to festival promoters, urging drug checking.

“We want you to have a good time at Bass Coast,” Forrester told Filter. “We don’t want you to have to spend your whole weekend in medical or in the sanctuary spot because you took something that wasn’t what you thought. By spending a few minutes getting your drugs tested and learning more about what it is and perhaps how potent it is, we can help you engineer a really great festival.”

The future of harm reduction, she added, is in “benefit maximization,” as the stigma around having a good time on drugs fades.

“It turned out to have no MDMA, and was just a mixture of fentanyl and caffeine.”

Nine times out of 10, the drugs tested at Bass Coast and Shambhala contained what was expected, according to analysis of the data collected from 2,700 participants last year. But when a bag supposedly containing MDMA is actually something else, or is of unexpectedly high strength, or cut with dangerous contaminants, festivalgoers who haven’t had their drugs checked can be in for heart palpitations, hospitalization or worse.

“Two years ago at a festival we had somebody with a drug they bought online that was supposed to be MDMA,” Antoine Marcheterre, the drug checking lead at BC’s interior health authority, told Filter. “It turned out to have no MDMA, and was just a mixture of fentanyl and caffeine.”

Marcheterre, who has worked with ANKORS to provide this service since 2017, noted that some people choose to bring fentanyl to festivals for their personal use, but that unintentional use by people without experience or opioid tolerance is significantly riskier.

In 2019, at the Bonnaroo festival in Tennessee, a 26-year-old man died with MDMA and fentanyl in his system—a combination that he likely did not take on purpose. Somewhat eerily, harm reduction activists had staged a protest at the festival earlier that weekend to raise awareness around fentanyl test strips—which were considered illegal drug “paraphernalia” in the state (prior to 2022 reforms), and were thus banned at the event.

One of the greatest benefits of drug checking is that it effectively leads to an improved drug supply, Marcheterre said.

One of the greatest benefits of drug checking is that it effectively leads to an improved drug supply, Marcheterre said. Drugs purchased at Bass Coast and Shambhala are almost 10 percent more likely to test as expected than drugs procured prior to the events, the data showed.

“We are a very drug-illiterate culture,” Chloe Sage, the Shambhala festival drug checking team co-lead, told Filter. She helped set up the program two decades ago with ANKORS. “We’re creating a harm reduction culture where you teach people the tools to take care of each other, and themselves.”

Festivalgoers have become vested in this culture, with attendees stumping up $20,000 for a 2018 GoFundMe campaign to enable the nonprofit to purchase a high-quality FTIR spectrometer testing device. Shambhala put up another $10,000; but that was exceptional, according to Sage.

“I’ve never [otherwise] heard of a festival actually putting money up for an organization to buy something like this with no strings attached,” she said. She pointed to corporate ownership of festivals as an obstacle to forward-thinking health policies.

“It’s a lot of work for us to convince promoters to let us provide our services,” Rae Elkasabany, the drug checking program coordinator at DanceSafe, a decentralized US harm reduction nonprofit, told Filter. Even when her organization succeeds in that, festivals may fail to properly advertise their services at the event and online. “They don’t want to get in trouble. It’s a high risk for them, because of our backwards laws.”

DanceSafe has conducted drug checking at festivals such as TomorrowWorld, Imagine, Mysteryland and Lightning in a Bottle. In 2015, however, during its fourth year at Electric Forest in Michigan, which was attended by around 40,000 people, event producers suddenly ordered the organization to close its booth, with no reason provided, it said at the time. DanceSafe was allegedly told to stop giving out an informational card about heroin because it was “too promotional.”

“Technically, we’re not allowed to say where we’re providing drug checking services,” Elkasabany said. “We operate in the legal gray area.” Times are changing, though slowly, she added.

In 2017, the Department of Justice clarified that providing drug education and free water is not a violation of the RAVE Act, while some states have permitted drug checking amid a US national toll of 300 drug-related deaths per day.

“There’s so many federal agencies using Burning Man as a training ground for their officers.”

Even in places which would be expected to be able to embrace drug checking, however, there can be challenges.

“There’s so many federal agencies using Burning Man as a training ground for their officers,” Taylor Wood, the drug checking program manager at the Chicago Recovery Alliance, told Filter. “The risk of getting arrested for possession is very high.”

In 2022, Wood and another team had planned to offer testing in a particular camp at the sprawling desert festival—but it got cold feet at the last minute. “We’ve had better success with underground raves and doing drug checking in those spaces,” he said.

Some activists therefore go renegade at festivals, conducting gonzo checking services with rudimentary testing equipment. Others are allowed to hand out fentanyl testing kits and naloxone at harm reduction booths—which are sometimes hidden away and not advertised.

While all of these measures help to reduce the risks of an unregulated supply, there is no panacea. “The complicated thing about drugs is that they’re just chemicals, but they’re chemicals that go inside people,” Macheterre said, “and people are complicated.”

Back at Bass Coast, the supreme high from the 2C-B is wearing off, and the advice not to take the entire dose has been vindicated. It might have been overwhelming.

All photographs by Mattha Busby