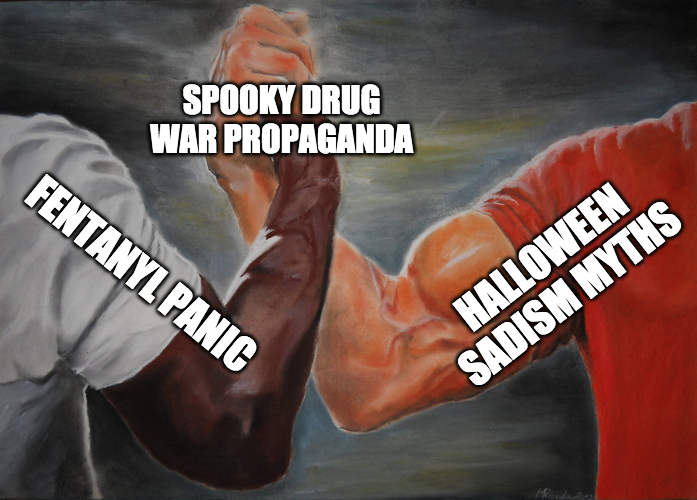

Frankenstein’s monster had nothing on this: A New Jersey beach town prosecutor’s office has been fusing together two damaging drug myths—fentanyl panic and Halloween sadism—just in time for the spooky holiday.

On October 25, a bag of what appeared to contain, and later tested positive for, heroin was found in a child’s candy haul in Cape May County. No one was hurt, and it was identified as “one isolated incident.”

Yet in the days that followed, local news channels covered the story, and the large media site the Daily Beast picked it up.

It’s a macabre escalation from the perennial marijuana-laced Halloween candy warnings, issued by police departments and gobbled up by media, that have become as closely associated with the holiday as pumpkins. (There have been no verified cases of harms caused by strangers handing out cannabis edibles to trick-or-treating kids.)

The seemingly irresistible narrative of malevolent others preying on children by giving them drugs on Halloween conforms to a tradition of misinformation dating back to the 1980s that sociologist Dr. Joel Best calls “Halloween sadism.”

Best has described the phenomenon as an expression of cultural anxieties, and said that it tends to be “particularly acute in years when some sort of terrible recent crime has heightened public fears.”

There is no shortage of possible causes in 2019. But fentanyl, which has become “America’s boogeyman,” said Dr. Ryan Marino, an emergency medicine physician in Cleveland, Ohio, may in particular be animating heightened public fears this Halloween.

“We’re in the middle of an opioid epidemic,” Michelle DeWeese, first assistant prosecutor for Cape May County, New Jersey, told local news. She’s right to note that New Jersey is being hit hard by the overdose crisis. Even as death rates in neighboring states like New York and Pennsylvania—and in the nation at large—seem to be beginning to trend downwards, New Jersey saw a spike in deaths between March 2018 and 2019.

But DeWeese’s additional statement—”It’s everywhere. It’s in our children’s trick-or-treat bags”—irresponsibly amplifies the Halloween-sadism mythology by peddling the false idea that fentanyl is creeping into domains beyond illicit drugs.

Marino fears that “the public perception is that fentanyl is a deadly powder that is sneaking into every aspect of life and can affect Jane and Joe Public”—which simply isn’t true. As well as fueling the anti-drug fears that prop up horrific policies like drug-induced homicide laws, this message serves to distract from the real issue: the people who use drugs who are dying preventable deaths.

Marino has seen such messaging in action in many places. One example is a new billboard campaign (below) in Cleveland, which aims to inform people about fentanyl’s potential presence in illicit drugs but ends up freakishly suggesting that fentanyl could also be in everyday consumer goods, like bottled water, donuts and trail mix.

Images from the Cleveland campaign InsideYourDrugs.com.

Not content with ramping up this year’s round of Halloween-sadism rhetoric, the Cape May prosecutor decided to give another platform to one of the most persistent myths about fentanyl’s effects. “If you do see anything suspicious [on Halloween] do not touch it because […] anything laced with fentanyl can be deadly,” said DeWeese.

The claim that merely touching the opioid could result in death flies in the face of the evidence. The American College of Medical Toxicology and American Academy of Clinical Toxicology asserted in their 2017 position paper on fentanyl exposure that “incidental dermal absorption is unlikely to cause opioid toxicity,” a finding that’s been supported Harvard Medical School professors and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Yet DeWeese has plenty of company. The touching-fentanyl-causes-overdose myth has been enthusiastically propagated by law enforcement departments, by the media, and by one of the CDC’s own videos.

Fentanyl, through panic and misinformation, has developed a near-supernatural reputation. It is involved in many deaths, but public outcry typically drowns out vital information about how to reduce risks, from naloxone to fentanyl testing strips.

There’s also another side to fentanyl—one that Marino will experience on Halloween while he is working in the emergency department.

“I will probably be giving fentanyl because it’s an extremely useful medicine in the emergency room,” he told Filter. “None of my patients will overdose on it. I wish people could hear that.”

Show Comments