A few months ago I caught a life-threatening blood infection from a dirty needle. Well, probably. I don’t know that the infection came from the needle. It could’ve been the towel I used to stem the bleeding, or a cooker. But that’s hardly relevant. The point is, I nearly died because for the first time, I was unable to access safe equipment.

Before the pandemic began to seriously affect the East Coast, I had plans to move to New Jersey, where my uncle lives. The virus meant I had to put my plans on hold and continue crashing with my immediate family in Washington, DC.

I had been staying with my family to save money. I had moved back in with them late last year after some health problems. After recovering, I went back to working in clubs and cashiered at a local gardening store during the Christmas rush—jobs that had evaporated by the time the lockdown began.

I knew I wouldn’t be able to handle staying with my parents—who reacted to first learning of my heroin use, three years ago, by invading my privacy and subjecting me to searches—if I didn’t have something to take. So in early April, I stocked up on enough of the opioid Dilaudid to last a few months.

I’d gotten the pills from a trusted friend who had, in turn, gotten them from a doctor. So they were all-but-guaranteed to be safer than the fentanyl-filled “heroin” available on the street.

Unfortunately, I was unable to acquire more than a small stash of needles. Ordering more online would be impossible, because my parents search my mail.

I would normally never reuse works; I’m well aware of the health issues this can cause. But it seemed that I had no choice.

Going to the local needle exchange wouldn’t work either. For one thing, the hours were far more restricted than usual. My parents also track me via my phone. If they saw that I was anywhere near Union Station (and, therefore, near HIPS), they’d search my bags and force me to throw out any harm reduction supplies. This has happened numerous times before. Then my mother would make me take a humiliating urine test, and when it came back positive, she’d force me to detox again by keeping me confined to my bedroom.

I would normally never reuse works; I’m well aware of the health issues this can cause. But it seemed that I had no choice. I figured that if I cleaned my supplies with boiling water and rubbing alcohol, I’d be okay. Of course, I wasn’t.

In the past, I’d always been able to access clean injecting supplies, as well as naloxone and fentanyl test strips. I’ve always been meticulous about hygiene and harm reduction, taking all available measures to avoid risk or contamination. Usually, I put used works in an old soda can to keep anyone from accidentally touching them before I dispose of them properly.

My sometimes-obsessive caution is partly why I’ve never overdosed or previously developed an infection. (I’ve been fortunate, too—for example in not experiencing dangerous adulterants that fentanyl strips wouldn’t pick up.)

So I really didn’t like the idea of reusing. I didn’t want to have to rely on frequent hand-washing, rubbing alcohol and covering my track marks in Neosporin. But that’s what I was left with to avoid going through sobriety at this already-awful time.

At this point, you’re probably wondering why I didn’t smoke or snort instead of injecting. The reason not to smoke was simple. My mother often smells my room to see if I’ve been smoking. She often claims to smell drugs even when everyone else agrees that it just smells like laundry and my perfume. I don’t know if she’s imagining things or pretending, but the end result is usually that she’ll use the alleged smell as an excuse to search for anything drug-related.

As for snorting, I can’t stand the way it feels. I also find that it doesn’t work very well. Most of the powder ends up in my throat, so I can’t measure the dose as carefully. If I take more to compensate for the stuff I swallow, I might OD; if I don’t, I’ll get dopesick. Injecting is far more precise. Plus, it’s cheaper because nothing is wasted.

At first my stash of Dilaudid really helped. Unlike street “heroin,” the feeling was consistent. It stayed in my system for quite a while, so I was able to deal with the strife in my family. I could sleep normal hours, something that’s virtually impossible when I’m sober. I made a fair amount of progress on my latest book. For once, things were actually going well. I spent my time working, reading and dancing.

But soon I began to feel strange. I’d been plagued by headaches since coming home from a writers conference a few weeks before. This hadn’t worried me; I often get headaches. My feet hurt almost constantly as well, due to my tendency to overexercise (I almost never take days off from dancing). So I’m quite used to ignoring pain.

And I did… until I began feeling weak and confused as well. I said odd things at dinner. I felt dazed all the time. One day, I awoke to find I no longer had the strength to perform my usual barre exercises. Suddenly I couldn’t even stand en pointe. Things only went downhill from there.

My lips were a bit blueish. I was struggling to breathe, though I hadn’t even realized it.

Shocked by my newfound weakness and confusion, my parents persuaded me to let them take my temperature. I had a fever of 103. A few days later, at dinner, my parents noticed that my lips were a bit blueish. I was struggling to breathe, though I hadn’t even realized it.

Then I woke up in the middle of the night, fighting for breath. My whole body shook from fever. That’s when my parents took me to the emergency room. I didn’t want to go—partly because it was almost time for my next dose of Dilaudid, partly because I didn’t have the energy—but I agreed anyway.

At the hospital I was immediately tested for COVID and came up negative. Despite this, the doctor concluded that I had a less serious case and sent me home with an inhaler and antibiotics. The former was to help me breathe, the latter to keep me from developing pneumonia. By the time I left the hospital I was already getting mild opioid withdrawal symptoms, though as usual I was able to conceal them. I’ve had lots of practice.

A few days later, I began to recover. I spent more time walking around and worked on my novel.

But then the weakness worsened. I continued to have fevers, ranging from 103 to 105. When the fever was at its worst I couldn’t stand. I felt horribly nauseous and dazed, and had to lean against something to stay upright. Simple things like reading, talking and typing took up much of my energy. It didn’t help that I rarely felt like eating.

For my 21st birthday, in May, my parents set up a video call with my relatives. I barely had the energy to sit at the table. Halfway through the call I had to return to my room, exhausted.

By then my stash of pills was starting to run low, but I continued taking them daily. They made the weariness and fever more bearable. However, my weakness and confusion made it harder for me to remember to clean my supplies.

I didn’t have the energy to boil water, so I just used cold tap water and alcohol. I also stopped washing the towel I used to stem the bleeding. I knew this wasn’t safe, but suspected it didn’t matter. I figured I was going to die of the fever anyway.

When I failed to recover after that trip to the emergency room, my family took me to see various specialists. For about a month, the doctors couldn’t figure out what was wrong. They took a lot of blood—not fun, because my tracks make me a hard stick—and ran all sorts of tests.

I became weaker still. Before long, I couldn’t even sit up unassisted. My fever and nausea continued. My body shook from the chills, and my bed was drenched in sweat.

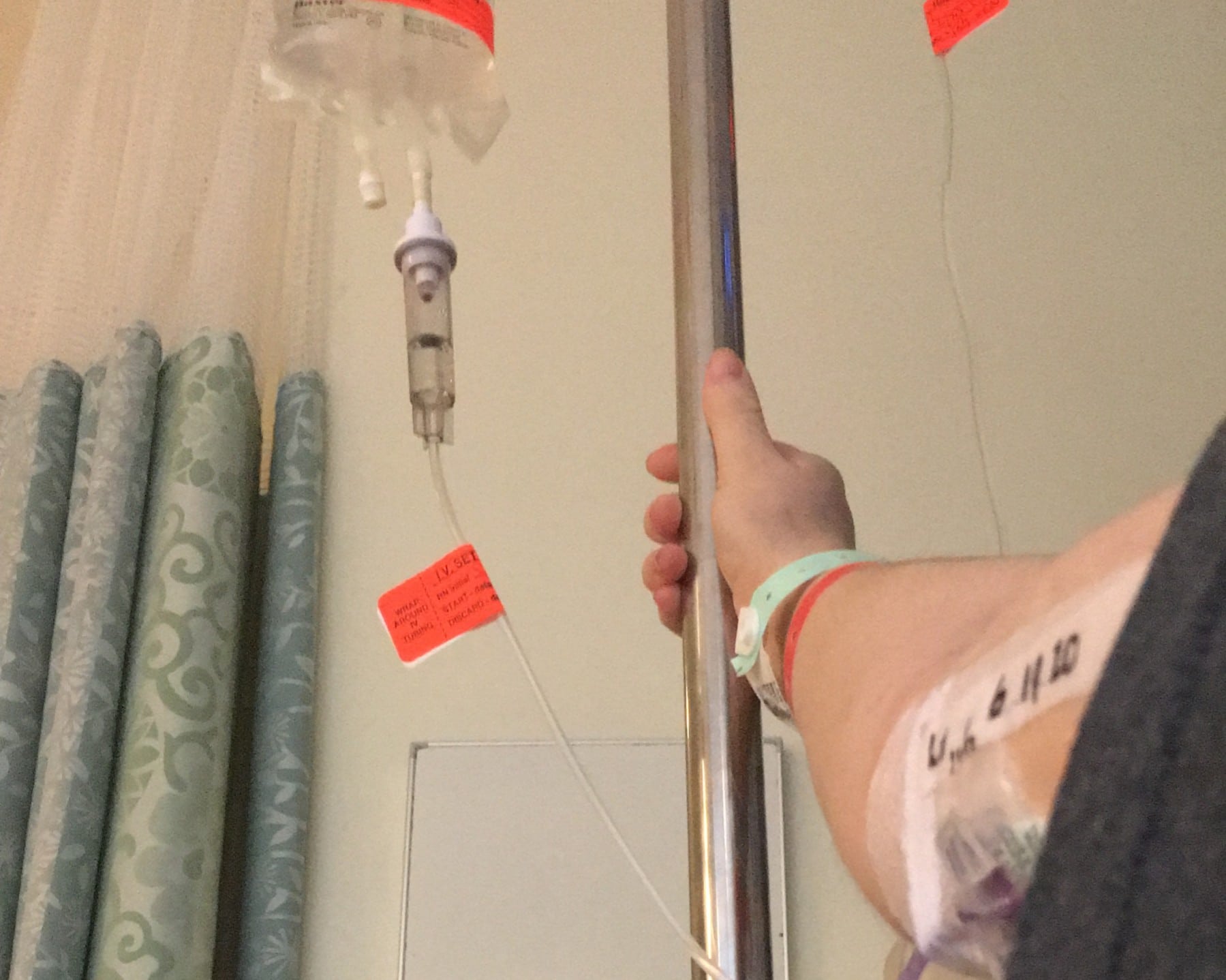

Mercifully, the doctors eventually figured it out. I had MRSA—a staph infection in my blood—and would need six weeks of IV antibiotics. The doctor said something about how lucky it was that they’d caught it when they did, given how dangerous this could be. If I’d been sick for much longer, the infection might’ve reached my heart. They told me to come to the hospital immediately.

Since I didn’t want the doctor to know what had caused the infection, I claimed I had been picking at a “cat scratch” I showed them on my wrist. It was really an injection site, but helpfully to my story, one of my family’s cats does bite and scratch whenever anyone tries to pick her up. Since the infection was caused by bacteria present both in most houses and on people’s skin, the doctors believed me. They did send a psychiatrist in to chat with me, because scab-picking is apparently a form of self-harm. But I managed to convince her that I hadn’t been trying to hurt myself.

As it happened, I had just run out of Dilaudid the previous day. So I went through withdrawal during my first week in the hospital in May. Again, I was able to hide my symptoms. I took twice the usual dose of my sleeping meds, having smuggled in a bottle. I forced myself to ignore the mental and physical anguish. Some of the associated symptoms could also be caused by the infection, so the doctors didn’t suspect anything.

If someone you care about is using drugs, offering the help they may need to secure these supplies could very well save their life.

After six boring, lonely weeks in the hospital, I finally got to go home on June 26. My fever had gone and I was getting stronger. My tracks had healed, leaving just thin purplish lines on my hands and arms.

I was still too traumatized to sleep in my old bedroom, where I’d spent those agonizing feverish months. My parents were kind enough to let me move into the library. I began dancing again. I continued working on my novel. Life went back to normal, thankfully.

I’m grateful to the people who took care of me as I got better. But all of this could easily have been prevented. I didn’t have to spend months shivering with fever, too weak to sit up. If I’d been able to order sterile syringes and other supplies for myself, I would’ve been able to stay healthy.

Even during a pandemic—in fact, especially during a pandemic—clean supplies need to be accessible. If someone you care about is using drugs, offering the help they may need to secure these supplies could very well save their life. Remember, I almost died at the age of 21 because my family refuses to believe in harm reduction.

Photograph courtesy of the author