A new report published by the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, examines how federal and state drug “paraphernalia” laws inhibit harm reduction. The authors—Jeffrey Singer, a physician and senior fellow at Cato, and Sophia Heimowitz, a public health researcher—urge policymakers to adjust their thinking from that of the failed drug war.

Though they acknowledge that more legislators are recognizing harm reduction as an evidenced-based approach to reducing drug-related death and disease, they detail how many states’ drug paraphernalia laws continue to block access to critical harm reduction tools.

Every state has such laws, ranging in effect from various restrictions to outright bans—with the perhaps-surprising exception of Alaska.

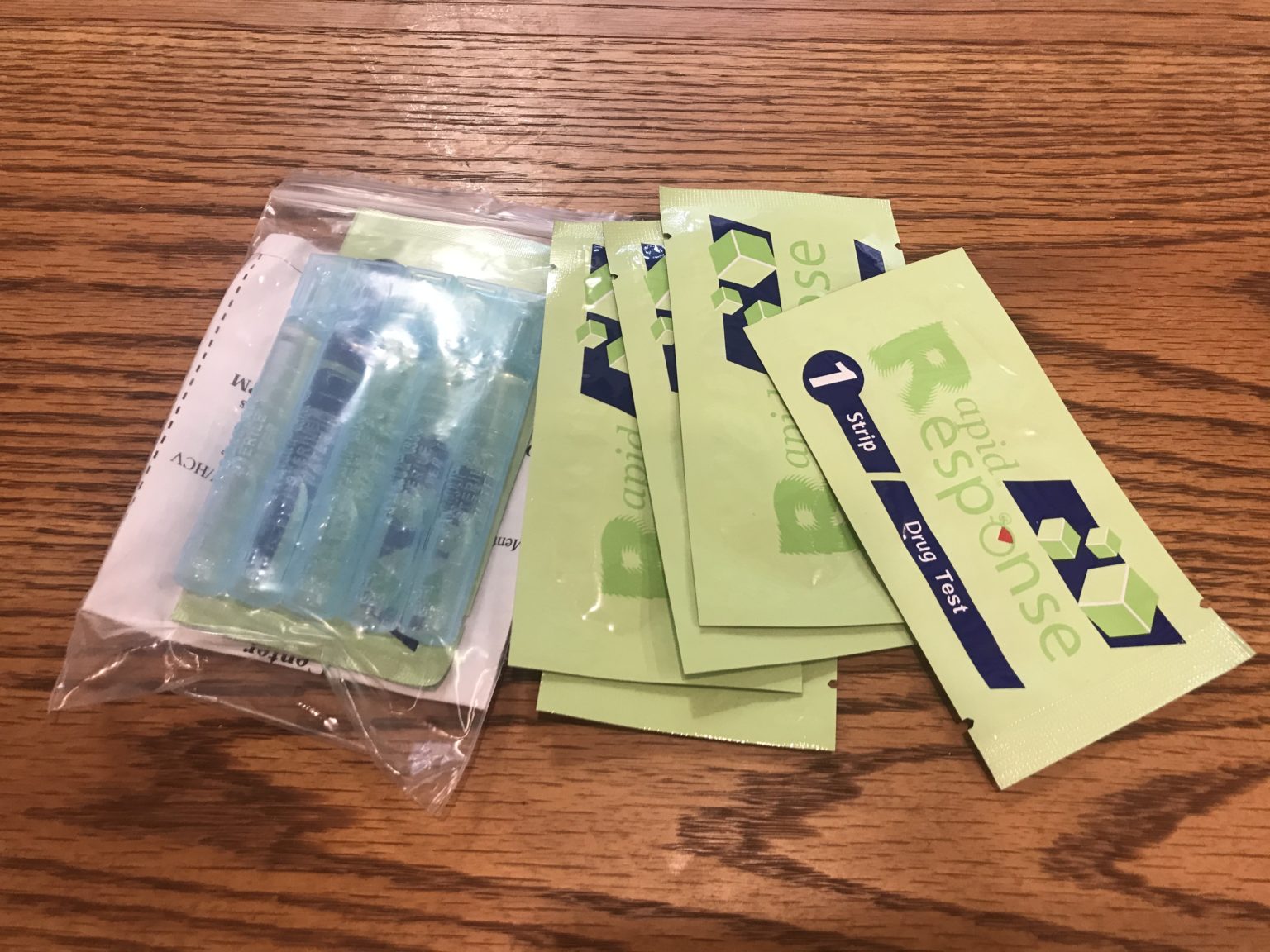

“The goal of drug paraphernalia policy should be to save lives by reducing the risks of overdose and disease,” the authors write. “This means removing government barriers to obtaining and distributing clean syringes and drug testing equipment.”

Graphics and tables in the report provide useful breakdowns of paraphernalia laws by state. And every state has such laws, ranging in effect from various restrictions to outright bans—with the perhaps-surprising exception of Alaska.

Despite the long-demonstrated efficacy of sterile syringe provision in reducing transmissions of blood-borne diseases like HIV and hepatitis C from shared needles, most states still include syringes in their laws’ definitions of paraphernalia. The exceptions are: Connecticut, Indiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Hampshire, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina and Wisconsin.

What’s more, six states—Connecticut, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Tennessee and Virginia—require a prescription for syringe purchases, even if syringe service programs, where supplies are given away, are exempt. Another 13 states—mostly in a central band of the country stretching from Texas to Minnesota—explicitly forbid syringe service programs.

When it comes to fentanyl test strips, which simply tell people whether the potent synthetic opioid is present in the drugs they plan to consume, only five states—Arizona, Nebraska, South Carolina, Virginia and Wyoming—do not explicitly include these tools in their laws’ definitions of “paraphernalia.”

“Paraphernalia laws increase the risk that users will lose their lives.”

“These laws are meant to discourage illicit drug use,” the authors write. “Instead, they produce avoidable disease and death. Drug prohibition puts peaceful, voluntary drug users at risk of losing their liberty and often their lives. Paraphernalia laws similarly increase the risk that users will lose their lives.”

They go on to highlight progress made by states that have amended or adopted new laws to encourage safer drug use. Arizona, for example, has recently amended its drug paraphernalia law to exclude fentanyl test strips, while the attorney general in Pennsylvania, as well as the district attorney in Philadelphia, have announced they will not prosecute people for possessing them, even as they remain illegal in the state. As Filter has reported, Ohio is among the states with current bills seeking to decriminalize the strips.

More states are authorizing syringe service programs to operate legally, yet many retain burdensome and unnecessary restrictions that hamper what they can do and, many times, where they can be. Earlier this year, as Filter reported, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy signed a harm-reduction expansion bill to remove a municipal ordinance requiring cities and towns to approve the programs in their jurisdictions. (The decision now falls to the state’s health department.)

Ultimately, Singer and Heimowitz call on legislators to move away from a zero-tolerance approach to drugs and embrace harm reduction. They encourage states to emulate Alaska, which allows residents to purchase any number of syringes and other drug-use resources, permitting anybody to run a syringe service program or practice other harm-reduction measures. They urge Congress and state governments to end drug prohibition, and—as is likely attainable sooner—to legalize harm reduction tools that save lives.

Photograph by Kastalia Medrano