A group of researchers have developed a comic designed to encourage veterans and health care providers to work together to reduce drug-related harms. The development process, which took several months, involved a group of veterans giving feedback to improve the content. The resulting comic should ultimately reach a wide audience through Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals nationwide.

“The graphic is as much education for veterans as it is role modeling [for providers] person-centered conversations in a health care setting about one’s substance use and risk reduction,” Justeen K. Hyde, PhD, assistant professor at Boston University School of Medicine, told Filter. She worked with the team behind the comic, and said, “The goal was to communicate messages in a graphically appealing way, and showing providers, ‘Here is some language to engage people in respectful conversations.’”

The VA is making an effort to integrate harm reduction in patient care, Hyde said, including by prescribing naloxone and sterile syringes, and offering overdose prevention education.

According to the VA, veterans are twice as likely to die of overdose as the general population in the United States, a situation related to physical, mental and socio-economic challenges in adjusting to life after service. Compared to the general population, veterans are at higher risk of suicide, mental illnesses like depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, and chronic pain. Among veterans who use drugs, injection-related injuries, infections and transmission of blood-borne diseases are also concerns.

They integrated a “co-design” team into the project—including eight military veterans with current or past experience of drug use.

In a paper about their work, published in the Harm Reduction Journal on December 6, the researchers explained how and why they created the comic.

After speaking with VA providers, the authors learned that doctors had little knowledge about injection drug use, and generally weren’t trying to talk to patients about it. Stigma around drugs posed a big barrier. So the researchers came up with the idea of a comic, using pictures and stories to educate doctors and patients about harm reduction, including naloxone, sterile syringes, and medicines like buprenorphine and methadone.

The researchers weren’t going do this without input from experts on veterans’ lives and health care. So they integrated a “co-design” team into the project—consisting of eight military veterans with current or past experience of drug use, plus doctors and nurses, harm reduction providers and other researchers. Along with a graphic designer, they all met over 10 sessions in a six-month period to create the comic, modifying it as participants gave their feedback.

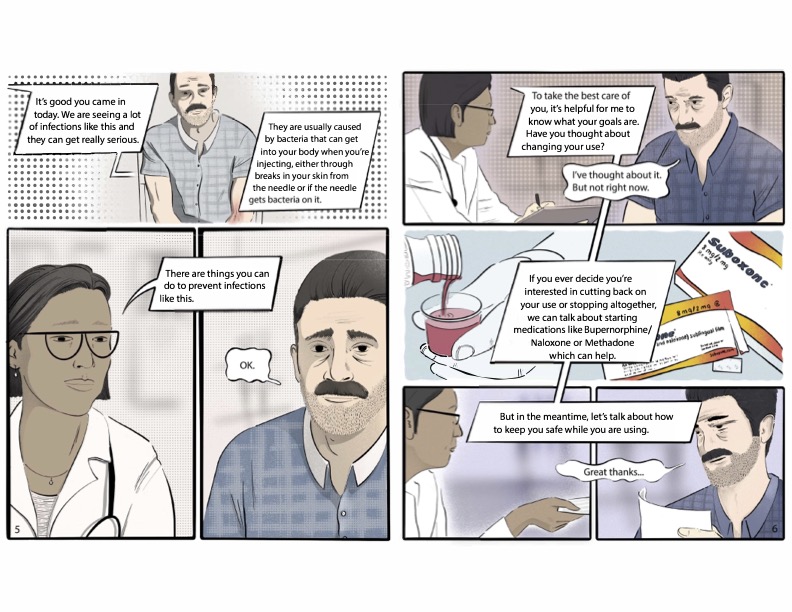

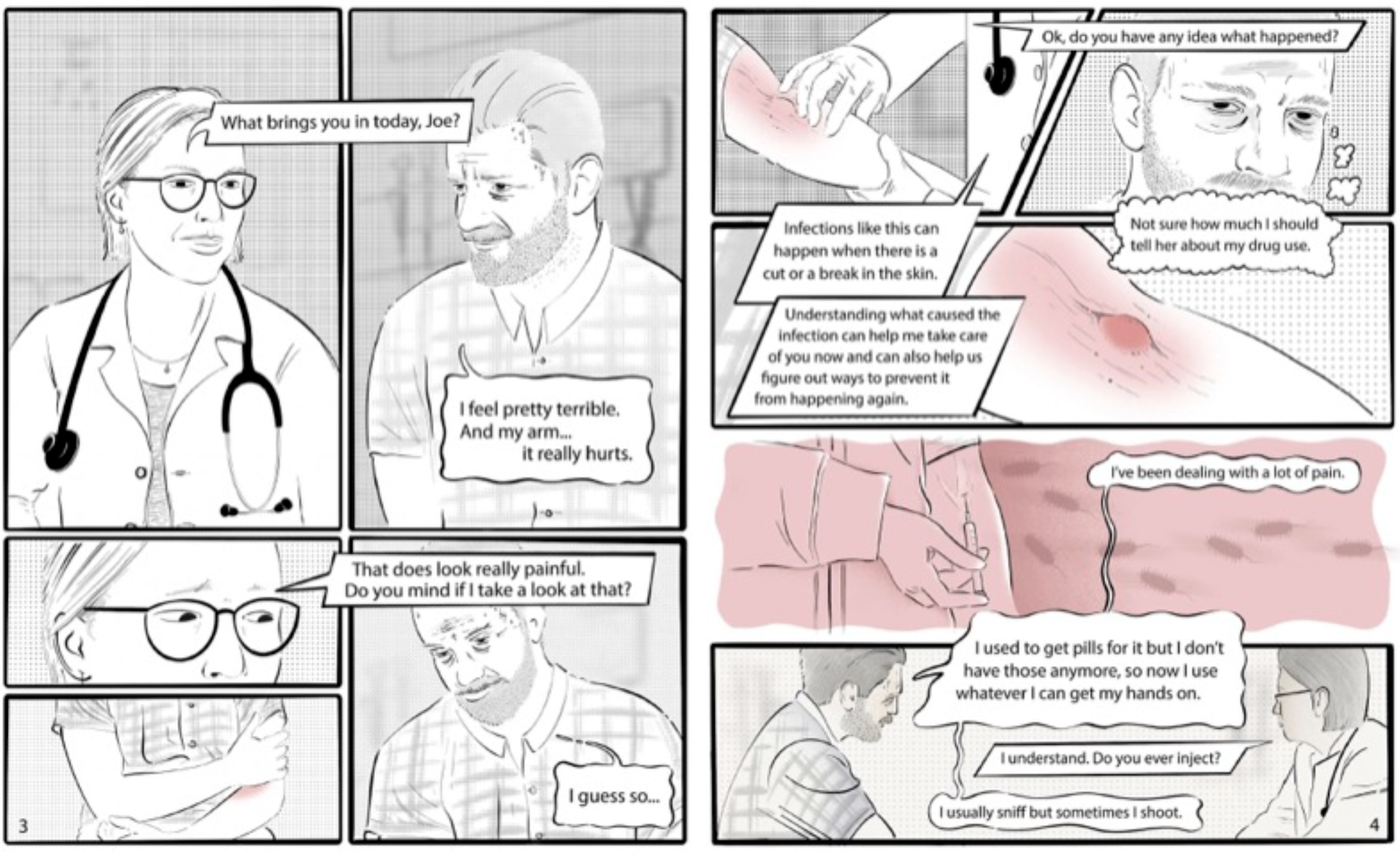

The final comic is titled “Your Health Matters: Let’s Talk About How To Stay Safe While Using.” It revolves around a fictional person named Joe, a veteran who visits the VA center with a painful wound on his forearm. The doctor immediately sees it’s caused by a cut or break in the skin, and asks Joe to explain how it happened.

“It’s helpful for me to know what your goals are.”

Joe is hesitant, and worries, “Not sure how much I should tell her about my drug use.”

So he simply tells her that he struggles with pain, and that “I used to get pills for it but I don’t have those anymore, so now I use whatever I can get my hands on.”

The doctor asks if he ever injects, and he responds, “I usually sniff but sometimes I shoot.” The doctor tells him his infection is caused by bacteria, potentially carried by the needle into his body.

“It’s helpful for me to know what your goals are,” she tells him. “Have you thought about changing your use?”

“I’ve thought about it. But not right now,” Joe replies.

The doctor mentions there are medications available that could help him. “But in the meantime, let’s talk about how to keep you safe while you are using.”

She then gives him advice about naloxone, testing his drugs, not using alone, cleaning the skin, always using sterile needles and other tools, testing regularly for HIV and hepatitis C, and avoiding injecting in the same place too much. Finally, she prescribes him antibiotics and naloxone, and tells him where to get sterile syringes—including at some VA clinics.

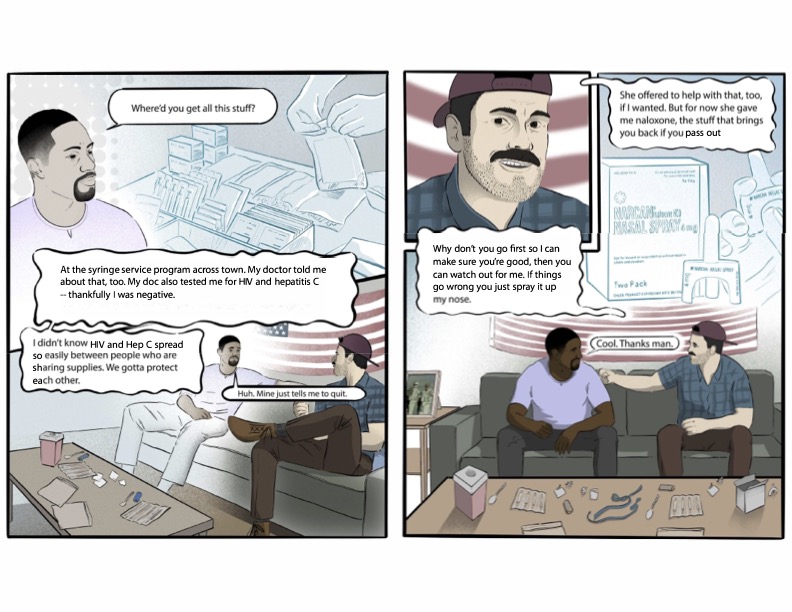

But the biggest breakthrough happens next: Joe is back home shooting up with his friend, who tells him to hurry. Joe pauses to clean his skin first, and shows his friend the harm reduction supplies he just picked up. He shares that he just tested negative for HIV and hep C, thankfully, and warns they need to be careful.

“Why don’t you go first so I can make sure you’re good, then you can watch out for me?” Joe offers. He grabs a Narcan. “If things go wrong you just spray it up my nose.”

As the researchers developed the comic, the veterans they consulted emphasized that it should be simple, relatable, and show doctors being approachable.

“It’s also important how the doctor presents himself,” said one veteran, according to the Harm Reduction Journal paper. “Eye contact; are you looking at the screen? Are you warm? Are you cold? Are you being a doctor or are you being a person who is someone you can open up to?”

“Doctors have to listen and hear, listen and hear—that’s what develops trust.”

“The line ‘let’s talk more about that’ always tends to reel me in,” another veteran said. “Listen to me a little more. The more they listen to me, the more I am giving out information every word I say.”

“Medical doctors always made me feel in fear that they knew me better than I did,” said a third. “That book-smart stuff scares me off. Doctors have to listen and hear, listen and hear—that’s what develops trust.”

The participants agreed that a comic can be helpful not just for the person reading it, but also for that person’s friends, loved ones and community. “If you educate the right person,” one said, “it gets back to the streets and they share the right information … When there is important information they spread it.”

Hyde explained how important it is for doctors to change how they approach drug-related injuries or illness, and to realize they already have some knowledge for how to treat patients.

“A very common reaction from providers is, ‘I’ve not seen anyone inject drugs, I don’t feel comfortable talking about this,’” she said. “But you actually do; you put in an IV line, you clean the skin, you use a new needle every time, you know what vein care looks like. So [we’re trying] to connect what they already know with ways to talk with people about staying safe.”

Hyde said the comic will now go to the Veterans Administration, where it will undergo additional edits before being distributed to clinics and hospitals throughout the country.

Images of the comic used with permission from Dr. Hyde

Show Comments