It took COVID-19 to do what the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the American Society of Addiction Medicine, the insurance industry, and the electronic health record industry have been trying to accomplish for years. The federal 42 CFR Part 2 regulation, which governs confidentiality of substance use disorder treatment records, will be greatly loosened under the CARES Act, signed into law by President Trump on March 27.

The $2 trillion stimulus bill rapidly hammered out by Congress was unprecedented in scale and impacts American life in all kinds of ways, so the insertion of this one little amendment may not seem like a big deal. But to patient advocates in the substance use disorder (SUD) treatment field, it is.

The first question many people ask when they go into substance use treatment is whether it will be confidential. Treatment programs now will have to say, no.

The CARES Act does not simply turn over all substance use disorder treatment records to the general Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) governing healthcare records. But it does mean that once a patient gives initial consent for disclosure of information, the patient then loses control of it.

Under the CARES Act, there is no way to segment the reason the information might be used in future.

You typically consent to release of your SUD treatment records upon admission to a program. This is required in order for the program to be paid by insurance. But under the CARES Act, there is no way to segment the reason the information might be used in future.

The three possible uses of this information that the Cares Act permits are: treatment, and obviously, you would want treatment providers to know you are being treated; payment, which is also a necessity unless you want to pay for it yourself; and then, healthcare operations. This last category is troublingly broad, and could result in disclosure to all kinds of people and entities beyond what a typical patient would wish.

Potential negative consequences are severe. Your divorce outcome could be affected, you could lose custody of your child, you could lose your job, or you could lose your freedom and go to jail. Down the road, many years from now, you could need cancer treatment and an insurance company could use your SUD history against you to deny payment. The stigma applied to addiction and the illegality of drug use mean that the possibilities are endless. Finally, there is such a thing as just wanting privacy.

Before CARES, there were rules against redisclosure. That is no longer the case. HIPAA will apply after the first consent, and the patient will have no control over how the information is redisclosed. And although the CARES Act says patients can revoke consent in writing at any time, exactly how that could happen once your information is in the electronic health record is unclear.

SAMHSA had previously been pressing for loosening of patient confidentiality and already has two rulemaking proposals on 42 CFR Part 2 in process, as Filter has reported. One would allow law enforcement to search records for patients on methadone. The other would radically change the regulation, allowing methadone patient information to go into the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP), as well as making other changes in confidentiality to appease the insurance industry. As of March 31, SAMHSA did not know, according to press spokesman Christopher Garrett, whether it would drop its 42 CFR Part 2 rulemakings in light of the CARES Act.

The new regulations from the CARES Act will not take effect for 12 months, but they’re coming. Advocates are deeply concerned.

“Revocation of data from those systems … would be technically improbable.”

“Once that information is available for any purpose under treatment, payment and health care operations contexts, it has already been shared with different contractor systems and potentially hundreds of individuals,” Danielle Tarino of Young People in Recovery told Filter. “Revocation of data from those systems, which then may continue to share data absent a prohibition on redisclosure, would be technically improbable. I have yet to come across a technical solution, protocol or even a strategy that could support this type of activity.”

The CARES Act stops short of saying methadone patient data can go into the PDMP—in fact, it says the “sense of Congress” is that it shouldn’t. However, maybe SAMHSA will decide to ignore the “sense of Congress.” SAMHSA has already made it clear that it wants methadone patient data in the PDMPs.

One result of COVID-19 is that telemedicine, including for both methadone and buprenorphine, will become a lot more common. While the CARES Act doesn’t specifically link 42 CFR Part 2 and telemedicine, there are many questions about how these online platforms are compliant with confidentiality. (Some, like doxy.me, are compliant with HIPAA.)

But HIPAA-compliant or not, there is just not going to be much enforcement of patient confidentiality, said Tarino, who used to work for SAMHSA. “The new lightened regulatory situation implies that there will be low prosecution and acceptances made amidst the COVID-19 crisis and provisioning of telehealth services,” she said. “That said, there still exists an ethical issue, and obligation of providers to ensure the protection of confidentiality and privacy via cyber services, to the best of their ability. In my opinion, that includes informed patient consent, or, at a minimum, conversation that is open and honest, when utilizing non-HIPAA compliant technologies.”

What would informed consent look like? These are the guidelines that Megan Marx-Varela, MPA, director of integrated care at Oregon Recovery and Treatment Centers (and formerly in charge of SUD treatment accreditation at the Joint Commission) told Filter she developed:

When meeting with patients for the first time via telehealth or telephonic connection please read the following statement to each patient:

“At this time, in accordance with federal guidelines on ‘social distancing,’ as well as state and/or local government bans or guidelines on gatherings of multiple people, your treatment program has elected to offer most treatment services via telehealth or via telephone. This is not how services are usually provided.

The federal government recognizes that we are currently experiencing a public health emergency and it is in the best interests of our patients and our staff to observe federal, state and local guidelines to prevent the spread of disease. During this time your treatment program may not be able to obtain your written consent for disclosure of your substance use disorder treatment records.

As a result, it is possible that patient identifying information held by your treatment program may be disclosed to medical personnel, without your consent, to the extent necessary to meet a bona fide medical emergency.

It is important for you to know that your treatment program is responsible for determining whether a bona fide medical emergency exists for the purpose of providing needed treatment, and they are required to document certain information in their records after a such a disclosure is made.”

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN

Essentially this means that patient identifying information about them may be released to medical personnel by the treatment program, without their permission, if the patient is experiencing a medical emergency. Typically, we would be required to obtain written consent from patients before we would provide patient identifying information, however, we may be unable to collect written consent while we are providing services via telehealth or telephone.

DOCUMENTATION (very important)

Please document that you have reviewed this information with the patient in the patient’s chart stating: “Reviewed COVID-19 Public Health Emergency Response and 42 CFR Part 2, disclosure of patient identifying information without consent for medical emergencies.”

If you really think that healthcare providers and authorities only want people’s substance use disorder treatment information for healthcare purposes, consider this: In August 2019, 32 Attorneys General banded together to call for the elimination of 42 CFR Part 2. Why would these powerful prosecutors want this?

Because under 42 CFR Part 2, a court order is required to obtain people’s SUD treatment information. Under HIPAA, no such court order is required. Things are going to take a bleak turn for vulnerable patients across the nation.

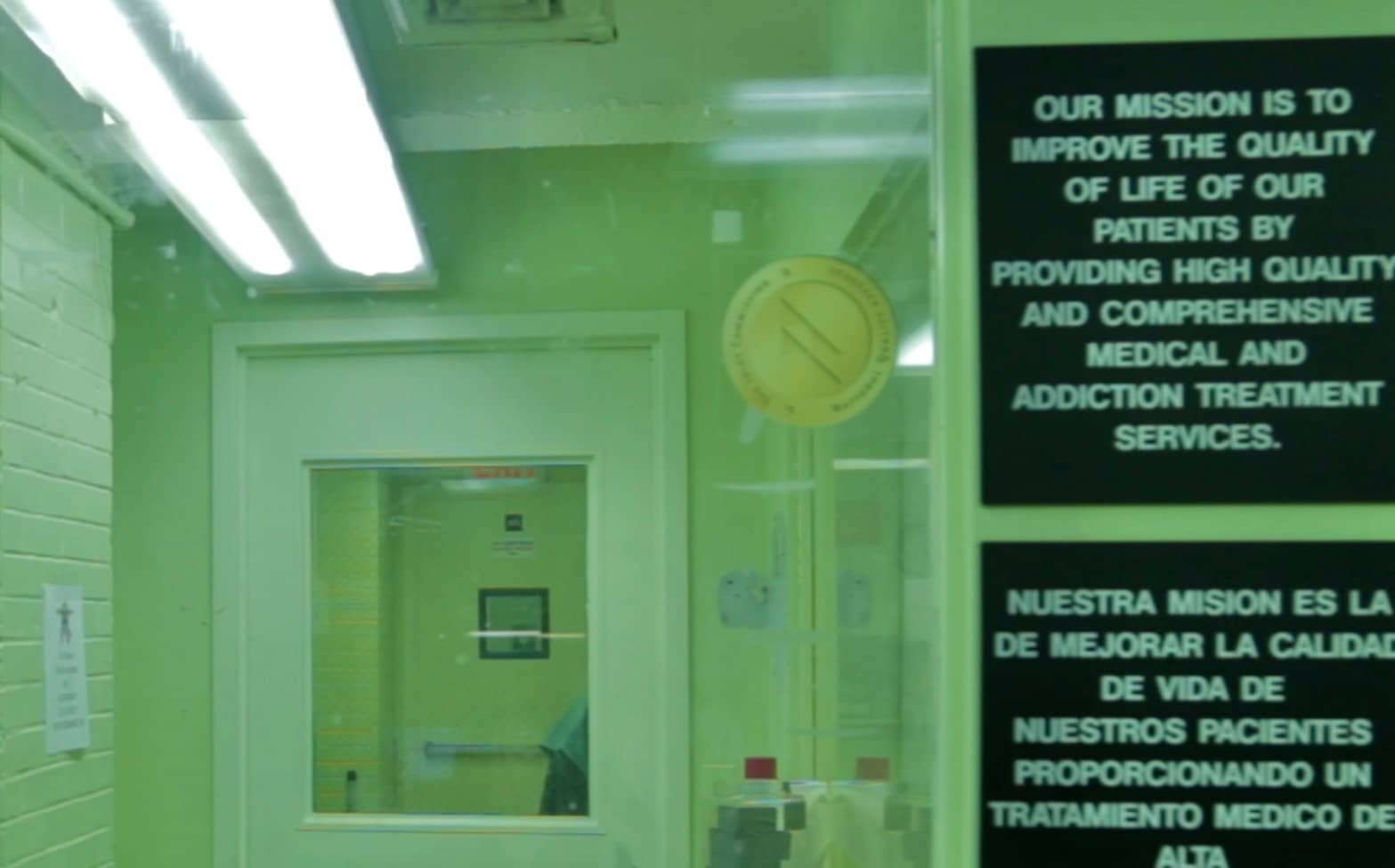

Photo of a methadone clinic by Helen Redmond