Of all the reformist prosecutors elected since 2015, almost none have been pummeled quite as much as George Gascón. Narrowly elected as the district attorney of Los Angeles County, California in 2020, Gascón may have underestimated the centrist bent of the county’s largely Democratic voter base and its on-the-ground law enforcement culture—despite his having once been the assistant chief of operations at the Los Angeles Police Department.

Any “cop cred” Gascón once had went out the window when he made the jump to prosecutor, serving as San Francisco DA from 2011-2019 before controversially switching to LA. His record in much of that time has been far from radical. He supported decarceration efforts like Proposition 47, which downgraded drug possession and low-level property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors; on the other hand, he refused to indict killer cops.

The relentless battles that have marked Gascón’s career are now coming to a head, as California’s Supreme Court weighs a major decision.

Yet, largely because of the nature of the state’s other DAs, Gascón has come to be seen as the arch-enemy of the state’s mass incarceration proponents. And the “tough-on-crime” lobby has repeatedly torn into Gascón. Seemingly every time a disgruntled right-leaning prosecutor left or sued his office, conservative national news joined the pile-on.

The relentless battles that have marked Gascón’s career are now coming to a head, as California’s Supreme Court weighs a major decision on the contours of prosecutorial discretion. Oral arguments in The Association of Deputy District Attorneys for Los Angeles County v. George Gascón are expected to be heard later this year.

Early in Gascón’s short tenure as Los Angeles DA, many of his deputy prosecutors revolted against his new policies, which included ending cash bail and not seeking the death penalty.

At the end of 2020, the Los Angeles Association of Deputy District Attorneys (LAADDA), the union that represents the deputies, sued to try to overturn some of Gascón’s policies—including advising the deputies to not use the state’s onerous “three strikes” law, which generates much longer prison sentences for people with prior felony convictions.

Proponents of “three strikes” and similar laws have long argued that it makes criminological sense to increase punishment for people who repeatedly transgress. Opponents point out that regardless of intent, these laws have little deterrent effect—and that the resulting sentences are unconscionably harsh.

LAADDA aggressively advocates against nearly all criminal justice reforms. The union is known for a hard-right ideology, and in 2022 its former leader made racist social media posts in attacking a Black DA special advisor to Gascón.

In the intermediate appellate decision, judges ruled that the state law must universally force prosecutors to allege prior felony strikes to ensure harsher prison sentences.

So far, the courts involved in LAADDA’s lawsuit against DA Gascón have shown little skepticism about the union’s motives. Most recently, the division of the California Court of Appeal based in Los Angeles mostly found in favor of LAADDA and against Gascón—despite being asked to rule the other way by illustrious legal names including arguably the top constitutional law expert in the country, UC Berkeley Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky.

In this intermediate appellate decision, the judges ruled that the state law must universally force prosecutors to allege prior felony strikes to ensure harsher prison sentences for defendants.

While prosecutors do not have to prove these strikes, they can’t just botch doing so in protest. Yet it is hard to imagine a decarceral prosecutor regularly having a good argument for being unable to prove a prior felony conviction. (All professional prosecutors, you would think, can easily find someone’s past criminal record.)

That leaves two options for a prosecutor like Gascón who wants to avoid three-strikes sentencing in California: dismissal of strike enhancements for “lack of sufficient evidence” of past convictions, which is never going to happen much; or their dismissal under a single mitigating law.

That law, Section 1385, does take into account many of the concerns of criminal justice reformers, such as disparate racial impacts and how trauma and mental illness contribute to the commission of crime.

In practice, however, courts find way to limit the applicability of mitigators. In the death penalty litigation world, for example, lawyers often argue about how bad a mental illness needs to be to matter. While bipolar disorder or schizophrenia may save someone from the death penalty, depression, no matter how bad, will almost never suffice. Similarly with trauma: If the trauma is not the result of truly despicable crimes committed against the defendant as a very young child, courts usually will not care.

So far, LAADDA is winning what many must feel is a rigged game.

As the case currently stands, it seems that executive branch power in California is weaker than many people thought. LA voters elected DA Gascón on a platform to reform the system, and accordingly he sought to do that, even if he’s never gone as far as progressives would want.

But the Court of Appeals ruling suggests that legislators alone call the shots, leaving elected prosecutors as cogs in a one-branch machine. So far, LAADDA is winning what many must feel is a rigged game.

The California Supreme Court will now have a chance to adjust this balance, in a way that could in practice spare many people years in prison, on Gascón’s watch and beyond.

Will it do so? In the last few years, the court has been willing to exercise its authority in sensible ways that made the “tough-on-crime” crowd angry, such as when it ruled that Proposition 66 (2016), which would have created an arbitrary five-year deadline for all death penalty appeals, was unconstitutional.

Proposition 66 had won the popular vote, just as Gascón would likely lose it today, because knee-jerk reactions on crime often win votes.

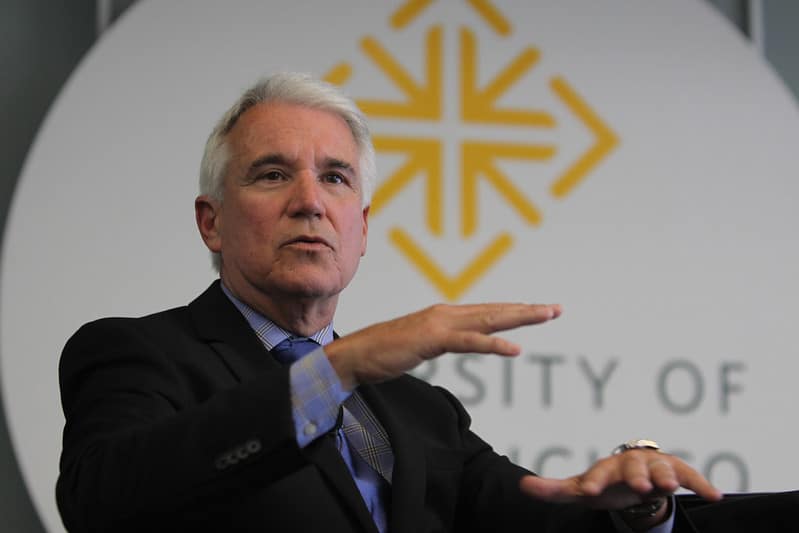

Photograph of DA Gascón in 2022 by Shawn via Flickr/Creative Commons 2.0

Show Comments