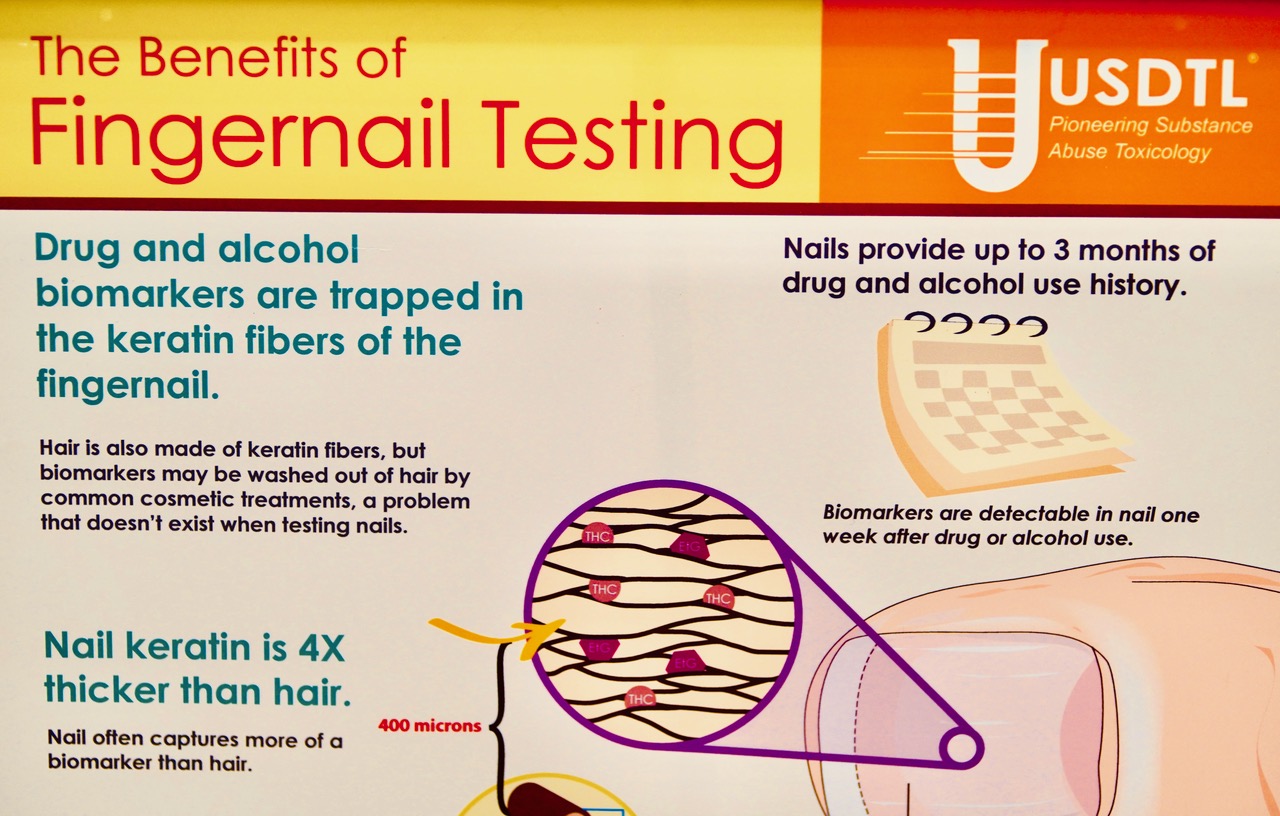

Apparently, fingernails and hair create “layers of drug history.” At the Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence (AATOD) conference, held in Baltimore in November, I wandered over to the United States Drug Testing Laboratories booth in the enormous exhibit hall, drawn to the company’s display. A green banner showed a goofy-looking white man sporting mirrored sunglasses on his forehead, with the words, “Get out of the ‘80s. Offer more advanced testing with higher panels, including fentanyl and Suboxone in hair and nail.” A cardboard poster showed a large, pink thumbnail: “Drug testing that looks back six months? It’s as simple as clipping the nails.”

It was eye-opening to see the industry all in one place. Methadone-clinic megachains BayMark and Pinnacle were joined by nine drug-testing companies, two corporations that make safes, a purveyor of high-density urine collection cups and technology businesses that have created a “video monitoring platform” and a GPS-enabled lockbox.

The federal agencies that wield so much power over the lives of methadone users were there, too: the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA)—together with the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF), a Silver Level sponsor of the event.

It’s a trade show for the methadone-industrial complex, its products and services designed for the constant control and surveillance of methadone patients, contributing to opioid treatment programs’ (OTPs) culture of cruelty.

At the Safes Security Services booth, the company had an array of safes on display. They’re marketed as “DEA compliant safes for methadone and all DEA scheduled drug storage.”

This bizarre obsession with high-security methadone storage reflects the DEA’s drug-war mentality.

The Megasafe corporation, meanwhile, has built a safe called the “Infinity Fortress.” The graphite gray door is “built to withstand the most concentrated and repeated modern day burglary attacks.” The safe can withstand two hours’ engulfment by fire. The salesperson told me the safes they sell weigh between 650 and 4,650 pounds. OTPs are important customers, he said. Also cannabis dispensaries, because they’re all-cash businesses.

A Safes Security Services sample

OTPs are a guaranteed market for these companies. DEA regulations mandate that clinics store methadone in a safe that weighs at least 750 pounds if freestanding. If it weighs less, it must be bolted to the floor.

This bizarre obsession with high-security methadone storage reflects the DEA’s drug-war mentality. It contributes to the creation of a carceral environment, in which OTPs view patients as inherently untrustworthy. And it promotes two other false notions. First, that methadone is highly dangerous—because if it weren’t, why must it be stored in an indestructible safe? And second, that clinics are natural targets for burglars—never mind that methadone has little street value.

In Porto, Portugal, I once watched peer harm reduction workers load bottles of methadone into vans; it was placed on the seat next to the nurse. There were no safes or security guards. And no robberies.

A methadone van in Portugal

The chronic opioid-involved overdose crisis has generated an opportunity for shrewd entrepreneurs to cash in on irrational fears about methadone safety. This reinforces stigma and spreads disinformation, often cloaked in the language of harm reduction and the concept of trust.

The preoccupation with locking things up and surveillance extends to bottles. MedLock, a “compliant packaging solutions” company, specializes in shatterproof, leak-resistant, plastic bottles to store liquid methadone. Its LiquiMedLock bottle has a tamper-evident band that breaks when it’s first opened for “clear chain of custody.” That carceral phrase refers to tracking and documenting each individual who handled the bottle.

MedLock also sells LiquiCapture urine collection cups that integrate a temperature strip, and a five-panel dip card for on-site drug testing. The company’s website states, “We take public health and safety very seriously and have designed our products to support harm reduction for addiction treatment programs.”

SafeRX sells the Locking Pill Bottle. It’s “pilfer-resistant” and “100 percent child safety certified.” The company was founded by Dr. Sean Serell, who states, “As the father of two young children, this growing crisis isn’t just alarming; it’s downright terrifying. Because the substance most widely abused by 12-13 year-olds isn’t tobacco or alcohol or marijuana. It’s prescription medication. And for teens, the #1 source of prescription medications is the family medicine cabinet.”

In fact, alcohol is the most widely used drug among youth, followed by experimentation with nicotine and cannabis. Prescription opioids like Oxycontin are no longer driving overdose deaths. Illicit fentanyl, which is, is not typically found in the family medicine cabinet. But those truths wouldn’t sell the SafeRX Locking Pill Bottle.

The companies that market these amber-colored containers need people to believe that it is no longer sufficient to put medication, especially opioids, in a generic, inexpensive bottle with a “push down & turn” lid. Now, we need “secure storage solutions to protect individuals, families and communities from improper access to medication.” That’s expecting way too much from a bottle!

Like MedLock, SafeRX claims its “locking prescription vials” are harm reduction.

The woman at the SafeRx booth showed me a large, cobalt-blue bottle with a cap that contained four hard plastic rings with numbers embossed on them. The cap is a combination lock. I had never seen a prescription bottle that looked so intimidating. I was given one for free and created a simple code to lock it. That night I tried to open it, but after numerous failed attempts resorted to a YouTube video for help.

Like MedLock, SafeRX claims its “locking prescription vials” are harm reduction. The website states: “Our roots are strongly grounded in creating products to support harm reduction programs within the substance addiction treatment space.”

These products are not about reducing harm, but making profits. The overdose crisis isn’t the result of easily opened pill bottles, and however “tamper-resistant,” no plastic container is unbreakable.

Cashing in on Take-Homes Surveillance

As a result of COVID-19, SAMHSA changed its guidelines to let more methadone patients take either 14 or 28 days’ take-home medication. Previously, it could take months or even years to “earn” take-homes. Not having to attend a clinic six days a week was liberating and life-changing for patients. This didn’t increase overdose deaths and “diversion” was rare, proving that people can safely consume methadone at home. (Unfortunately, OTPs have scaled back or entirely eliminated the reform.)

Investors and physician-entrepreneurs saw SAMHSA’s revised guidelines as a fresh opportunity to make money. Verinetics and Sonara are two of the companies attempting to disrupt the take-home medication system.

A video at the Verinetics booth caught my attention. It showed patients, umbrellas in hand, standing in line in the rain. The caption read, “Every day individuals with OUD wait in OTP lines like this one to receive their methadone dose … How do you get your kids to school or get yourself to a job?” Verinetics is acknowledging the clinic-generated barriers patients have endured for decades.

Its mission, it says, is to make opioid use disorder medications “safer and more accessible to more patients.” So it designed DispenSecur—a heavy, bulky lockbox that can hold up to 12 bottles. These are dramatically different from the clunky lockboxes patients currently use to store take-home bottles. DispenSecur has an embedded 5G radio that is linked to a cloud-based portal, and includes real-time inventory tracking and analytic software.

Perhaps the most “Big Brother” feature is that at any moment, it can be locked remotely by clinic staff, cutting off patient access.

A Verinetics sales representative showed me how the bottles are loaded into a carousel; a metal cover then locks into place so patients can’t see or access all the bottles. A small green door opens at a predetermined time, and only one bottle can be taken out. The video showed how OTP staff log into a dashboard that displays if the methadone dose was taken as scheduled or skipped, or if a bottle is missing. Through geofencing technology, a Google map shows the “last known location” of DispenSecur.

Perhaps the most “Big Brother” feature is that at any moment, it can be locked remotely by clinic staff, cutting off patient access. DispenSecur can also go into lockdown mode if it detects signs of medication theft or tampering. A digital screen displays a message to the patient, “Device locked by OTP,” and gives the clinic phone number.

The sales rep walked me through how the software allows staff to lockdown DispenSecur and then unlock it. An information sheet stated, “Locking may be invoked if a provider has concerns about the patient or medication … it can be used to encourage a telemedicine session.”

This feature is sheer cruelty. It lets patients know loud and clear that they are not in control of their medication, not even in their own home. The potential to use it to coerce and punish is enormous.

Verinetics asserts that DispenSecur “fosters trust”—that word again—between patients and OTPs. But how does a device that enables “providers to monitor medications from the time patients leave the clinic to the moment they access each of their daily doses of methadone” foster trust? It doesn’t. Constant surveillance is the opposite of trust.

Verinetics was awarded $1.5 million by NIDA to develop DispenSecur, which the company calls an “alternative solution that increases access to take home methadone privileges through ‘remote supervision’ and autonomous dispensing deactivation.”

“If history is any indication of how technology gets used when it comes to people who use drugs, then we can expect bad consequences.”

Such devices put people who take methadone between a rock and a hard place—dangling a degree of freedom from the clinic, but at a price. You can take methadone at home and avoid the commute and the bullshit at the clinic, but you’ll be under constant surveillance and can be cut off at any time.

“If history is any indication of how technology gets used when it comes to people who use drugs,” Aaron Ferguson, the methadone liaison for the National Urban Survivors Union, told Filter, “then we can expect bad consequences—intended or not—to result from looking for new ways of demanding accountability.”

Verinetics’ tagline is, “Better Control for Controlled Substances.” More accurate would be, “Total control over people who take methadone at home.” Currently, DispenSecur is an investigational device and not for sale. I hope it never is.

The story of Sonara begins with Dr. Michael Giles. During a psychiatry residency rotation at the Veterans Administration OTP in Dallas, he “witnessed firsthand the hardships patients had to go through.…” So what did the doctor do? Giles conceived of a “medication adherence ecosystem” that he believes facilitates “humanized, compassionate and trustworthy interactions between clinic patients and providers.”

Like Verinetics, Dr. Giles wants patients to get more bottles of methadone more quickly to take at home, so he designed a mobile app. Patients are given methadone bottles with QR codes. The labels are “tamper-aware” and state, “DO NOT open until instructed.” At a time designated by the OTP, patients scan the QR code with their phone camera. Once scanned and opened, the QR code is voided and the label indicates that it has been opened.

The camera then turns on, and a video stream of the patient drinking the methadone is uploaded to Sonara’s “secure repository.” Clinic staff review the footage. It’s a remote version of the in-person dosing observation that clinics subject patients to every day.

A lot can go wrong with this kind of an app, in particular for patients who are on low incomes, unhoused, disabled or have mental health diagnoses. Phones get cut off for nonpayment, or are stolen or lost. Using the app correctly demands a certain level of tech savvy. What if the recording is out of focus or doesn’t show complete ingestion of methadone? What happens if the video can’t be uploaded to Sonara? Lots of people don’t have consistent access to the internet or wifi, especially in rural areas. Others don’t have phones at all, meaning they’d presumably be excluded from take-homes under this system. The digital divide is real.

Like DispenSecur, the Sonara app promises liberation from the OTP, but in return, patients must submit to regular monitoring.

Sonara says its “patient-facing application supports “low-end, government issued mobile devices, low-bandwidth and internet connectivity…” It doesn’t say how.

The company also developed an app for OTPs that gives staff information about patients’ dosing outside of the clinic setting. It displays how many doses were submitted, rejected, missed or incomplete. Sonara says its product can “boost take-home accountability and transparency.”

“‘Patient accountability’ is a term never uttered in other areas of healthcare,” Ferguson responded. “The concept could be applied to anyone seeking health care services, but it isn’t, because [other] providers actually care about the patient experience and keeping them in treatment.”

It’s inevitable that staff will use the information from recordings to force patients back to daily, in-person dosing. Like DispenSecur, the Sonara app promises liberation from the OTP, but in return, patients must submit to regular monitoring.

Sonara cell phone stand

When I met Dr. Giles, I asked about the name of the company. He said it comes from the Spanish word soñará, which means “will dream.” I wondered what his dream was about, because the app he created seemed more like una pesadilla (a nightmare). I told him the use of the Sonara app would result in the punishment of some patients. I tried to explain OTPs’ culture of cruelty. Giles was annoyed, and said, “If you write something critical, it will hurt patients.” He then informed me that there was a 90 percent patient satisfaction rate for the app.

Sonara has partnered with BayMark and other OTPs to test the app, and also received funding—more taxpayer dollars—from the National Institutes of Health and NIDA to conduct research. Last year it launched the Remotely Observed Methadone Evaluation (ROME) study with the aim of “developing and integrating Machine Learning features such as facial recognition and methadone vial position tracking for automated dosing event interpretation.” More Big Brother.

If adopted widely, this technology has the potential to end all unsupervised dosing. And there are financial incentives to do so.

“We certainly understand remote observation may be viewed by some as patient surveillance,” a company representative told Filter in a later email. “Sonara is a tool to minimize barriers that prevent patients from receiving take homes and/or increased take homes. Since eligibility is at the discretion of the OTP and subject to bias, remote observation can help strengthen the trust between OTPs and patients and alleviate concerns regarding diversion. Our hope is remote observation can help increase equitable access to take homes and demonstrate that patients are indeed trustworthy and can safely handle increased take homes.”

Currently, if a patient has take-home bottles of methadone, they’re stored in a locked box with no surveillance technology. Trust has been established in the sense that they’ve followed clinic regulations and “earned” the “privilege” to take methadone in the privacy of their home. When they take their medication, or even if they skip a dose, it’s their own business.

DispenSecur and Sonara turn all that on its head, extending the power of OTPs to high-tech spying in a person’s home. If adopted widely, this technology has the potential to end all unsupervised dosing. And there are financial incentives to do so. OTPs get paid for supervised dosing, but not unsupervised.

Methadone patients shouldn’t have to prove they can be trusted to take their medication without being watched, but thousands recently did. “If the evidence from COVID wasn’t enough to show that people who use drugs deserve less, rather than more, monitoring, then I’m not sure what would be,” Ferguson said.

The devices and systems showcased at the AATOD conference are nothing more than high-tech ways of policing methadone patients for profit.

Update, February 16: This article was edited to include mention of Verinetics’ grant from NIDA.

All photographs by Helen Redmond

Show Comments