The Progressive movement established drug prohibition, including alcohol, in the early 20th century by utilizing racism and classism. Today public health, embodied by alcohol epidemiologists at the World Health Organization (WHO), claims to draw conclusions based on evidence. But they mold their recommendations to fit a temperance worldview. Doing so is becoming increasingly challenging in light of their own findings.

The Back Story

The WHO created a worldwide impact by publishing its Global Burden of Disease study (GBD) in 2018, covering the years 1990-2016 and involving 195 countries. The international GBD consortium of researchers concluded that there was “no safe level” of alcohol consumption. This conclusion was ballyhooed around the world. Public health specialists in the US were especially receptive to this message, which was amplified throughout American media and health news outlets. Meanwhile, at its “Alcohol Facts” website, the WHO lists solely negative consequences of drinking alcohol.

But the WHO’s claims that alcohol’s effects are all bad have been contradicted by epidemiological studies in the US and other wealthy nations, which consistently find net longevity and cognitive gains resulting from 1-4 drinks daily.

One large-scale demonstration of this contrary result came from the Journal of the American College of Cardiology in 2017. Based on data from 13 waves of the National Health Interview Surveys linked to the National Death Index records, 333,247 Americans aged 18 and older were analyzed. The results: “Compared with lifetime abstainers, those who were light or moderate alcohol consumers were at a reduced risk of mortality for all causes.”

This reduction in deaths was due primarily to reduced cardiovascular disease, the biggest killer in the United States.

The New Global Burden Findings

Such evidence has continued to mount, and now comes from a source that will be inconvenient to the WHO. In July, GBD published a larger (200+ countries), more detailed, updated analysis of the impact of alcohol worldwide in the Lancet. Its published conclusion was: “Small amounts of alcohol might lower the risk of some health outcomes but increase the risk of others, suggesting that the overall risk depends, in part, on background disease rates, which vary by region, age, sex, and year.”

That’s a pretty unilluminating conclusion. The Lancet provided a slightly more digestible summary of the results:

For adults over age 40, health risks from alcohol consumption vary by age and region. Consuming a small amount of alcohol for people in this age group can provide some health benefits, such as reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and diabetes. [My emphasis.]

Could You Be More Specific?

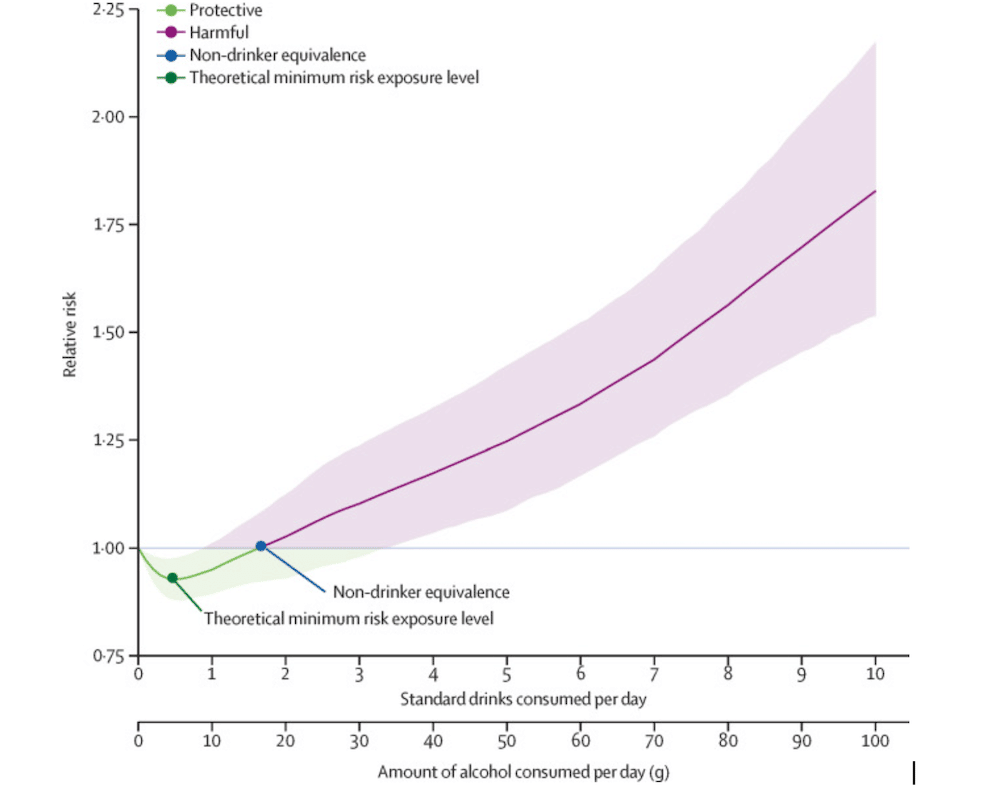

Before turning to the actual results, there are a couple of relevant terms you should know: DALYs (disability adjusted life years) measure years lost through premature disability and death for each disease; NDE (non-drinker equivalent) is the alcohol consumption level at which the health risk is equivalent for drinkers to that of non-drinkers.

At what level of drinking do drinkers and abstainers have the same DALYs?

Alcohol benefits, computed worldwide, are standard for people aged 40 and over who drink moderately.

Among people aged 40-64, GBD found, “the global NDE in 2020 was 1.7 standard drinks per day among males and 1.8 standard drinks per day among females.”

More strikingly, for those 65 and older, average NDE nearly doubled—to 3.2 standard drinks per day for men and 3.5 standard drinks per day for women.

Most critically, any amount below the NDE level, but not abstaining, lowers a person’s relative risk for disability or death.

In GBD terminology, alcohol has a protective effect. Alcohol benefits, computed worldwide, are standard for people aged 40 and over who drink moderately. A typical 40-to-64-year-old who averages somewhere under two drinks daily will live longer, and without disability, than a typical person who abstains. At 65-plus, “drinking moderately,” as measured globally by GBD, extends to somewhat more than three drinks daily. A typical 65-year-old who has three or fewer drinks daily will live longer and more healthily than a typical abstainer.

GBD alcohol risk table for all subjects worldwide. (Relative risk is pegged to abstinence = 1.)

The other finding that’s hinted at in this global report is that there are distinct, identifiable groups for which drinking is beneficial around the world. These are primarily age groups. Results did not differ significantly between men and women.

These age differences are standard in alcohol health studies. Advantages are little noted in younger populations. Yet positive as well as negative effects are accumulating all along. These benefits start to appear in early middle age and are accentuated in later life. They are due to the substantial effect of alcohol on the atherosclerosis (blood artery clogging) that causes the major killers of heart disease and ischemic strokes, as well as for diabetes. These conditions, and alcohol’s mitigating effects on them, largely only begin to emerge around age 40. Their appearance accelerates around age 65 for both men and women.

The problem for the WHO now becomes how to spin the results.

But the GBD result was stunning! Even those whose research has identified benefits due to drinking must be impressed at such a clear-cut and substantial advantage for drinking, calculated globally for mature and older drinkers.

Even as a non-temperance advocate who has always noted alcohol’s benefits, I am somewhat surprised by these results indicating universal benefits from significant levels of drinking. I am surprised because I have emphasized cultural influences in causing addiction and alcohol-related mortality. Ironically, the pro-temperance alcohol epidemiology movement represented by WHO and its Global Burden of Disease study has vividly alerted me to alcohol’s direct medicinal properties.

Now What?

The problem for the WHO and the temperance nations that overwhelmingly dominate international alcohol epidemiology now becomes how to spin the results. They must go from “there is no safe level of drinking” to “there are clear and substantial health benefits from alcohol that appear at age 40 and increase the older one becomes.”

Again, these results show that alcohol has beneficial effects globally. Up to almost two drinks daily reduces mortality and disability for people over 40 around the world. These benefits extend to over three drinks daily after age 65.

Is this information worth knowing?

The WHO and US public health specialists would never baldly state this substantive finding. Instead, they dispense the bromide that alcohol may be beneficial, but that depends primarily on where you’re located and your age.

True, as it goes. But is this the best message for Americans and many others to receive? Is this the well-intentioned dissemination of useful public health information? Or is it the defensive posturing of an entrenched temperance worldview in long-term retreat?

Photograph by Marco Verch Professional Photographer via Flickr/Creative Commons 2.0

Show Comments