Life expectancy in the United States plunged by a year and a half in 2020, the worst year-on-year change since World War II. Drug overdoses were the second-most influential factor, behind the obvious: COVID-19. Fatal overdoses reached their highest recorded levels last year: 93,000. The surge continues into 2021 and is dovetailing with an unfathomable related crisis: a national shortage of naloxone, the “antidote” to opioid overdose.

The drab Pfizer website lists the availability of its injectable naloxone formulation as “depleted.” In a perfect world, Pfizer’s listing would be banal. A shortage of one generic WHO-declared essential medication for one manufacturer (among several in the US) doesn’t sound like a crisis scenario. Yet Pfizer’s supply disruptions are causing the worst naloxone shortage the country has faced since at least 2012, when overdose levels were less than half of what they are now.

Insiders confirm that the shortage has devastated community-based naloxone distribution.

The Opioid Safety and Supply Network (OSSN) Buyer’s Club is the largest source of naloxone distributed to directly to affected communities—accounting for 1.3 million doses in 2020 alone. And the Buyer’s Club has relied solely on naloxone from Pfizer at a specially negotiated price.

In late April, Pfizer quietly communicated that naloxone supply would be interrupted, toppling what was already a precarious distribution network. Insiders confirm that the shortage has devastated community-based naloxone distribution, as the Buyer’s Club is the single largest distributor in most states.

Pfizer did not respond to Filter’s request for comment.

“I would guess that the naloxone shortage is related to redeployment of pharmaceutical production resources to COVID-related work, as well as the general chaos in manufacturing and transport,” Leo Beletsky, professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University, told Filter. “Pharmaceutical supply chains have been in total disarray.”

Fewer than half of harm reduction organizations in an OSNN member survey provided to Filter report receiving any federal funds (including federal funds routed through state agencies) to purchase naloxone. Some innovative purchasing mechanisms have been created and painstakingly maintained in the face of perpetual budget scarcity.

The OSNN Buyer’s Club collectively purchases large volumes of naloxone as an informal network of 108 harm reduction programs sprawled across 39 states and DC. Much like how the Veterans Administration is legally able to negotiate prices directly with pharmaceutical companies (unlike Medicare) and therefore has some of the lowest drug prices, the OSNN negotiated a lower purchase price directly with Pfizer.

Harm reduction organizations have now been relegated to purchasing their naloxone at prices orders of magnitude higher than before, greatly reducing the amount they can afford.

The Affordability Problem

Recently, the federal government approved the largest-ever appropriation for harm reduction at $30 million, and an even larger appropriation that also removes the long-standing ban of federal dollars being used to purchase syringes is set to pass. It should be a time of hope in the harm reduction world, after decades of being underfunded and dismissed by the federal government.

Instead, organizations across the country are scrambling to provide their communities with the life-saving medication central to overdose prevention. As naloxone grows more scarce, people are reverting back to materials not needed in nearly a decade, posting resources on social media about what to do in an overdose when there is no naloxone.

Community-based naloxone programs have found that people who use opioids themselves are most likely to use naloxone to reverse an overdose, making them the priority population for naloxone distribution. Highly marginalized people are also most susceptible to barriers such as cost. Naloxone is not free, though people who use drugs typically acquire it at no-cost from harm reduction programs. The cost barrier, previously detailed in Filter, is the chief reason access is still limited.

Syringe service programs (SSPs) depend on injectable naloxone because it is most affordable. They distribute high volumes into their communities, primarily among people who use drugs and are most likely to be present during an overdose.

A July 8 NASTAD (National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors) memo states that between 2017 and 2020, SSPs distributed 3.7 million doses of generic injectable naloxone purchased through the OSNN Buyer’s Club. At that volume, cost savings immediately translate into more doses that can be purchased—and more overdoses that can be reversed. The memo goes on to list potential supply shortage mitigation strategies for SSPs, striking a hopeful chord in an attempt to ward off the panic that is brewing in the field.

Without access to affordable injectable naloxone, there is renewed interest in why Narcan is so prohibitively expensive.

Purchasing naloxone directly from pharmacies is possible, whether for harm reduction organizations or individuals. One dose of the injectable version of naloxone is listed on GoodRx and CMS at just below $15, though it is unclear how that price will fluctuate as the market shifts. Overdose reversal kits as compiled by harm reduction organizations include either two or three vials of injectable naloxone, reflecting that some overdoses require more than one dose. So if organizations were forced to purchase their naloxone at market rate, it would cost over $30 per person, multiplied by the thousands of people they may serve.

The nasal spray formulation Narcan, meanwhile, is listed on both GoodRx and CMS at around $128. (Note: CMS lists it per dose but it is sold per two-dose package.) Even people who aren’t purchasing high volumes suffer sticker shock at that price and hesitate. It makes scaling up Narcan distribution to a level required for saturation unfeasible.

Yet as things currently stand, harm reduction organizations scrambling to acquire any naloxone at all may end up purchasing Narcan to exhaust their time-limited grants before the end of the cycle; Emergent Biosolutions, its manufacturer, is poised to see its profits surge right along with overdoses.

Without access to affordable injectable naloxone, there is renewed interest in why Narcan—generally preferred for its ease of administration—is so prohibitively expensive. Under FDA patent law, Narcan is a “combination device”—both a drug and device packaged together. The cheap cost and multiple generic offerings of the actual compound within, the naloxone, become irrelevant in the face of this designation.

Recently, a second company, Hikma Pharmaceuticals, has patented Kloxxado, an ethically questionable higher-dose nasal spray formulation, indicating that equivalent technology is not prohibitively difficult to replicate. Competitors offering similar nasal naloxone combination devices could enter the market which would, in theory, bring down the price.

Potential Interventions

The “free market” isn’t the only potential solution to the crisis, however. In 2017, former President Donald Trump declared the ”opioid crisis” a public health emergency. It was more than political theater: The declaration of a public health emergency is a legitimate legal framework that expands government options to act and opens up funding streams. HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra extended the declaration in July 2021.

“A ton of these public health powers that we have seen used in COVID can be used here,” Jennifer Oliva, public health law scholar at Seton University School of Law, told Filter. “All of this federal stuff on the federal level is triggered by a declaration of emergency. The federal government can use its public health emergency powers under a number of different statutes and extend liability waiver, bulk purchase, stockpile, do all kinds of stuff.”

“In a more functional society, you would think, ‘These are essential medications, we need some sort of biosecurity structure.'”

Beletsky noted that such critical supply problems are neither new nor limited to naloxone. “Currently, we offload the production of essential medications onto the private sector, supported by taxpayer funds,” he explained. “We get very poor results in terms of supply and competitive pricing.”

“A big structural intervention could be getting the federal government actually involved in the production of essential medications, especially those in shortage,” he continued. “In a more functional society, you would think, ‘These are essential medications, we need some sort of biosecurity structure to ensure these are being produced at adequate quantities and getting where they need to go.’”

Even without such federal intervention, more could be done. A naloxone distribution problem has long been recognized. Some agencies, such as law enforcement, get more than they need, while others struggle to get any at all. Transporting naloxone from an area of surplus to an area of shortage is complicated by wildly varying state laws that require a complex chart to interpret. So the drug does not always get into the hands of the people most likely to use it, instead expiring on the shelves of clinics and police departments.

“We can’t just freely offer our extra [doses] to somebody else,” lamented Ella Bannister, founder of the Alabama Harm Reduction Coalition, “because it was technically bought through a specific grant with specific deliverables through federal funding. I find that that’s a big barrier as we move through this shortage.”

Many federal grants are routed through state agencies. While grantees have myriad requirements to fulfill, the state agencies are provided little oversight.

“There are all kinds of regulations for us when we receive grants, so why aren’t there stricter regulations for the federal government?” Bannister asked. “They could put in a percentage of how much needs to go to smaller nonprofits, places that actually serve individuals who use, rather than just allowing [the state] to decide what they want to do with it.”

“It is really going to take every organization across the US coming together.”

Extreme fragility in the US naloxone distribution network—caused by chronic underfunding, and compounded by egregious and unregulated drug prices—left it susceptible to minor fluctuations. Then a global pandemic brought major disruption. At a time of unprecedented overdose deaths, it will be harder than ever to get naloxone into the hands of people who need it until at least this fall.

“This is a crucial time to be able to have [injectable] naloxone because we have such [overdose] surges,” Bannister said. “And it just doesn’t seem possible.” As for a solution, “It is really going to take every organization across the US coming together.”

Harm reduction—a field and a movement that’s used to operating in precarious conditions with resourcefulness and tenacity—will surely find ways through the current shortage. Many people who need naloxone will not.

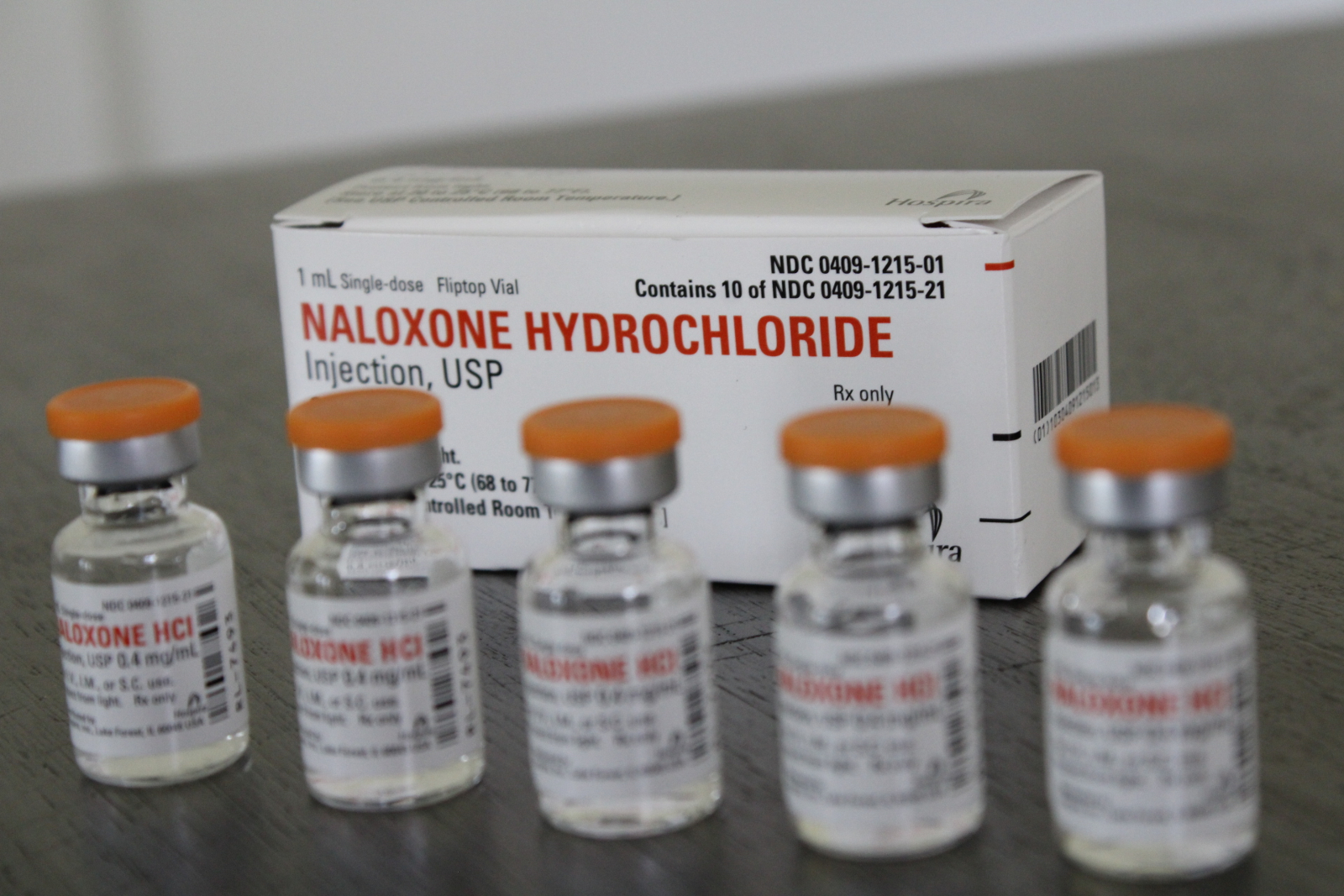

Photograph by Morgan Godvin

Jacob Sherkow, professor of law at the College of Law, University of Illinois, provided background information to Filter on FDA and patent law.

Show Comments