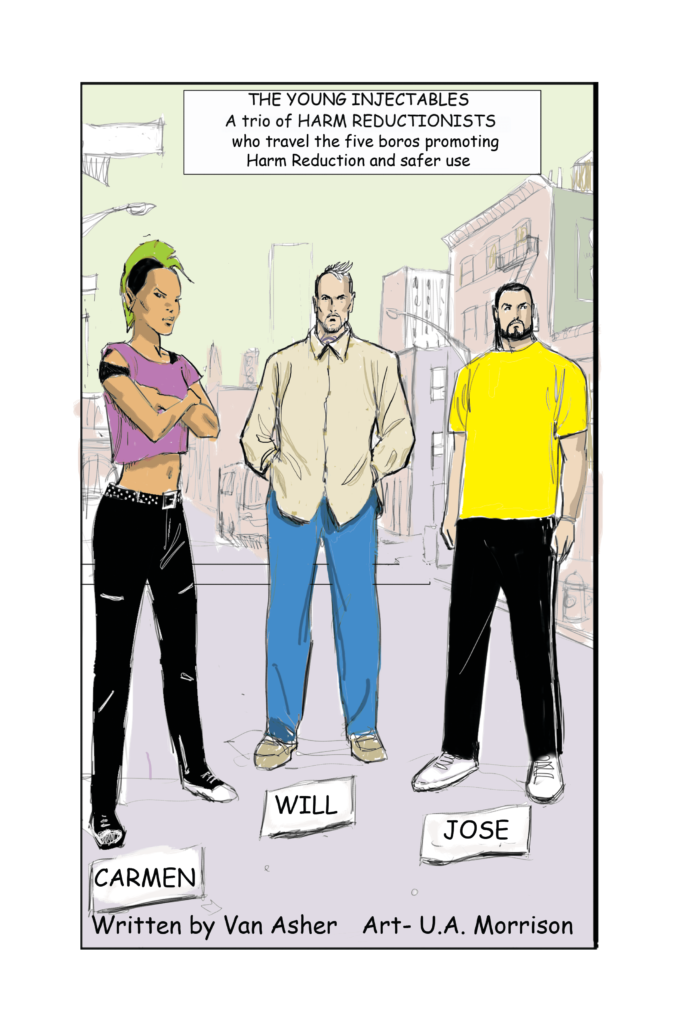

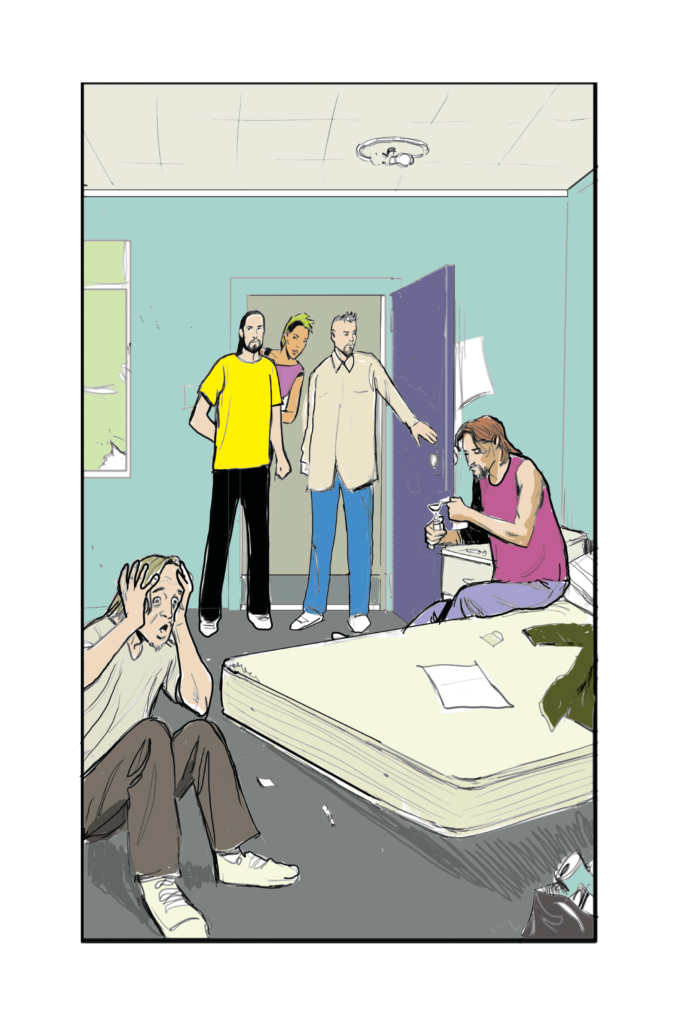

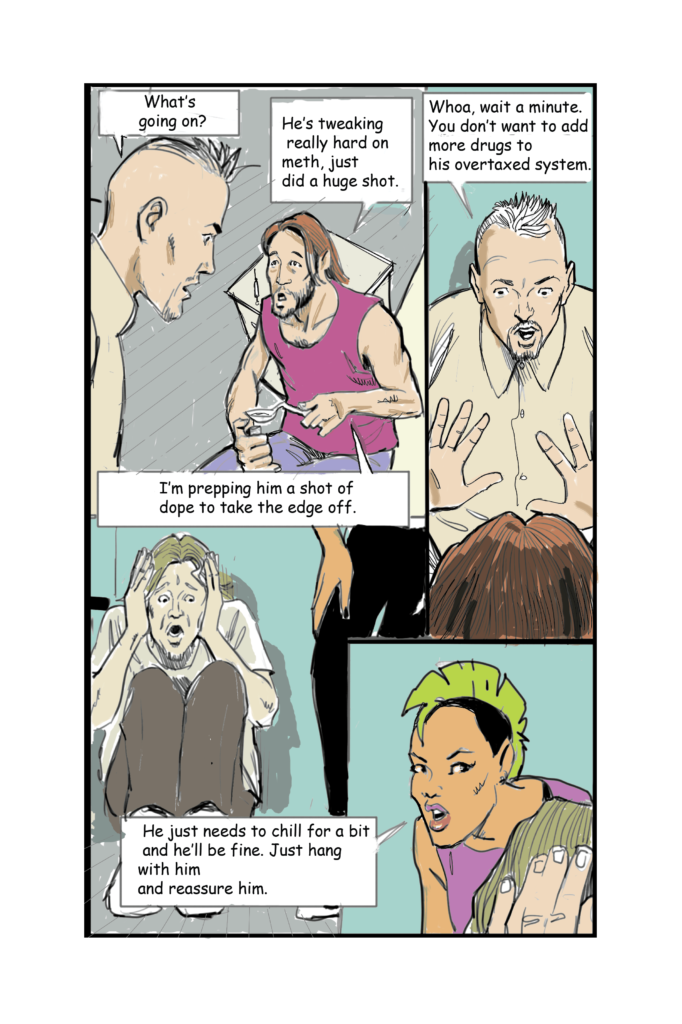

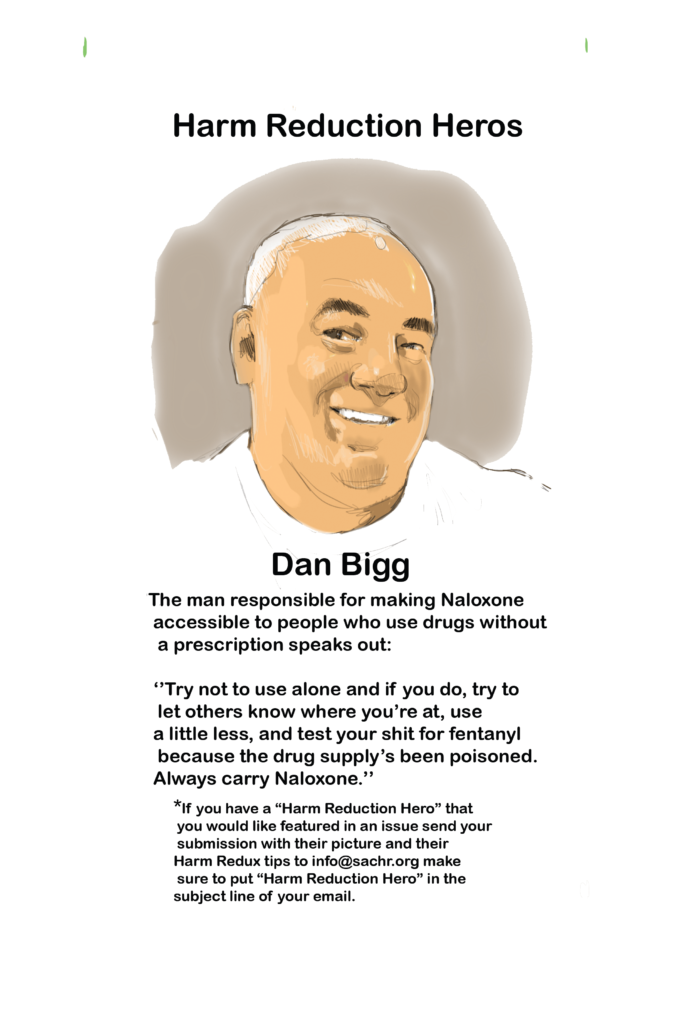

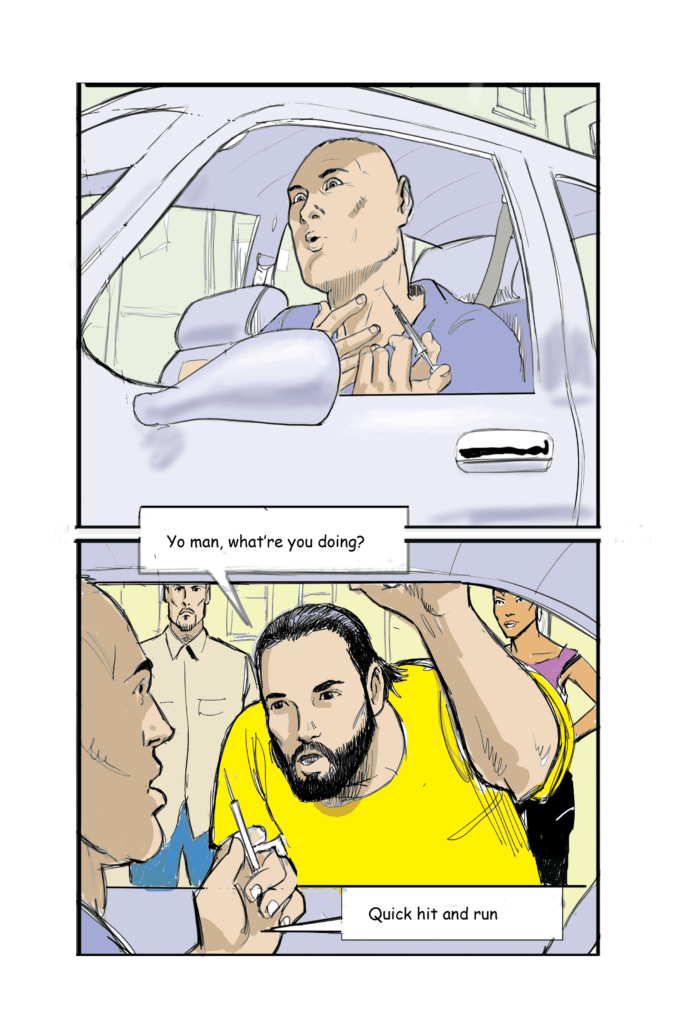

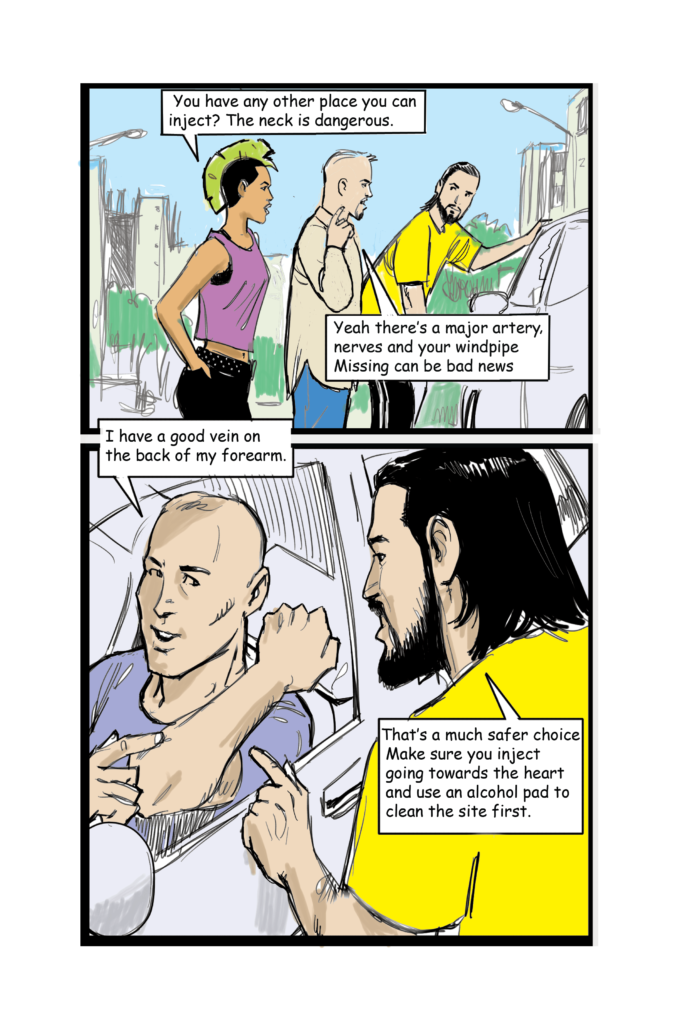

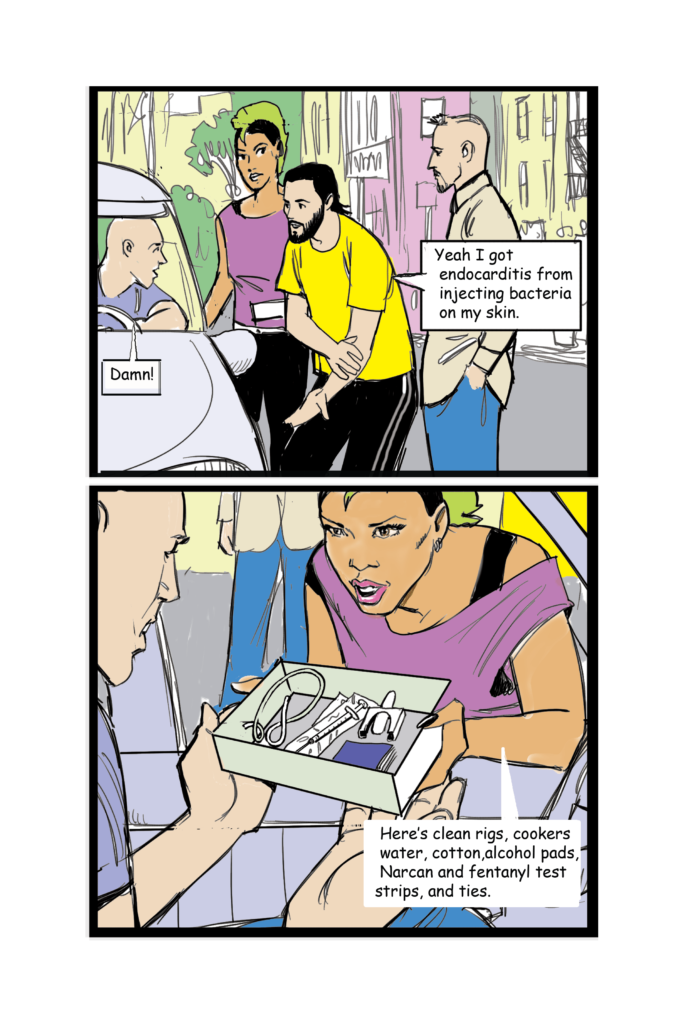

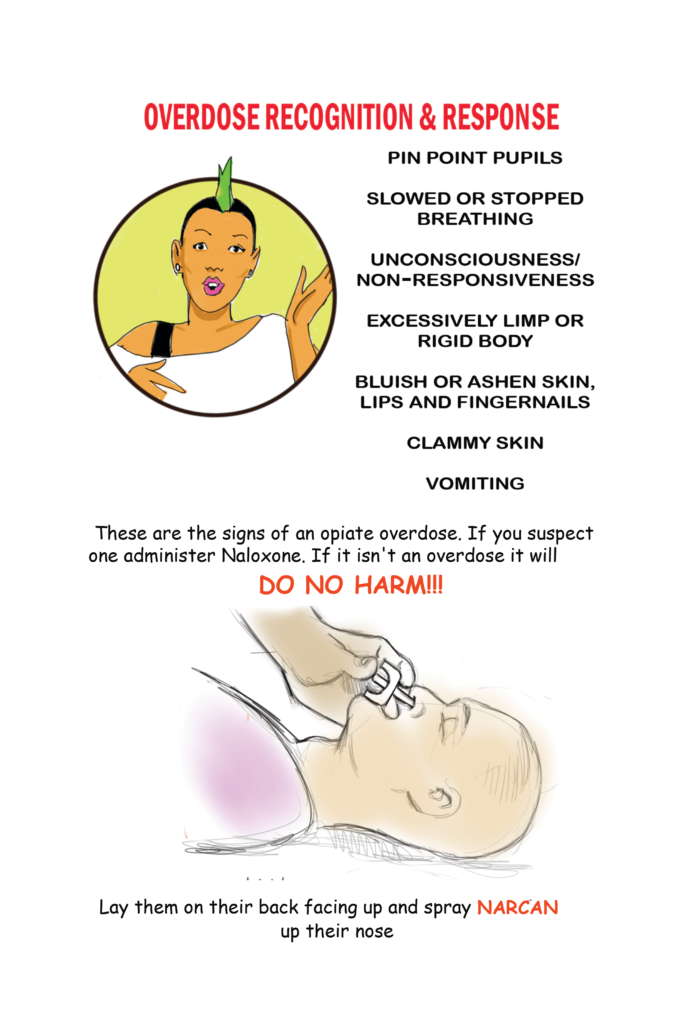

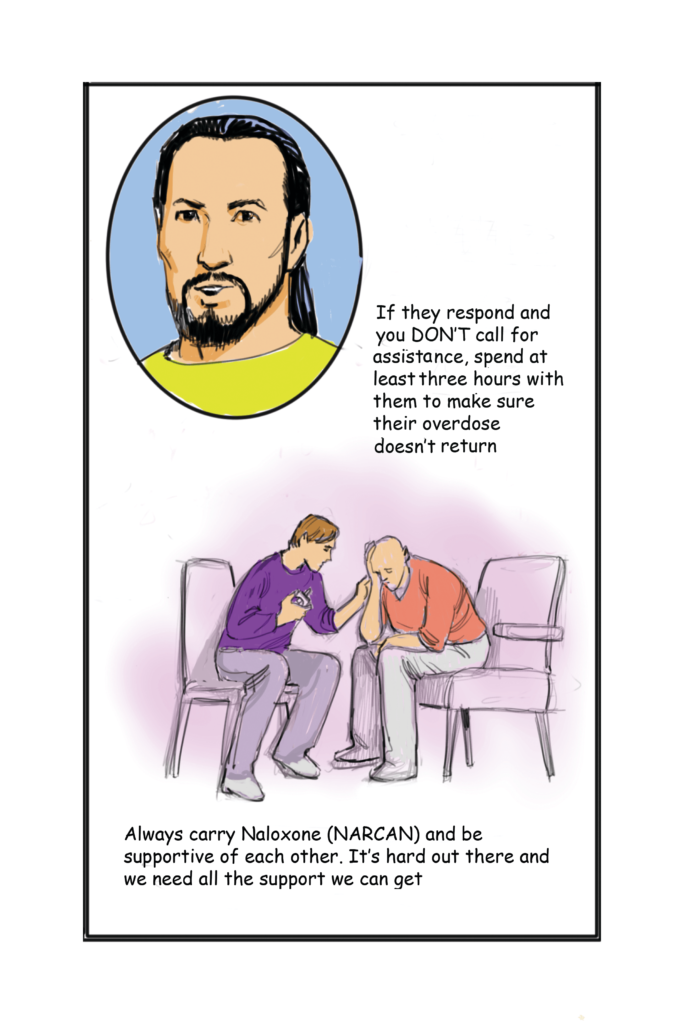

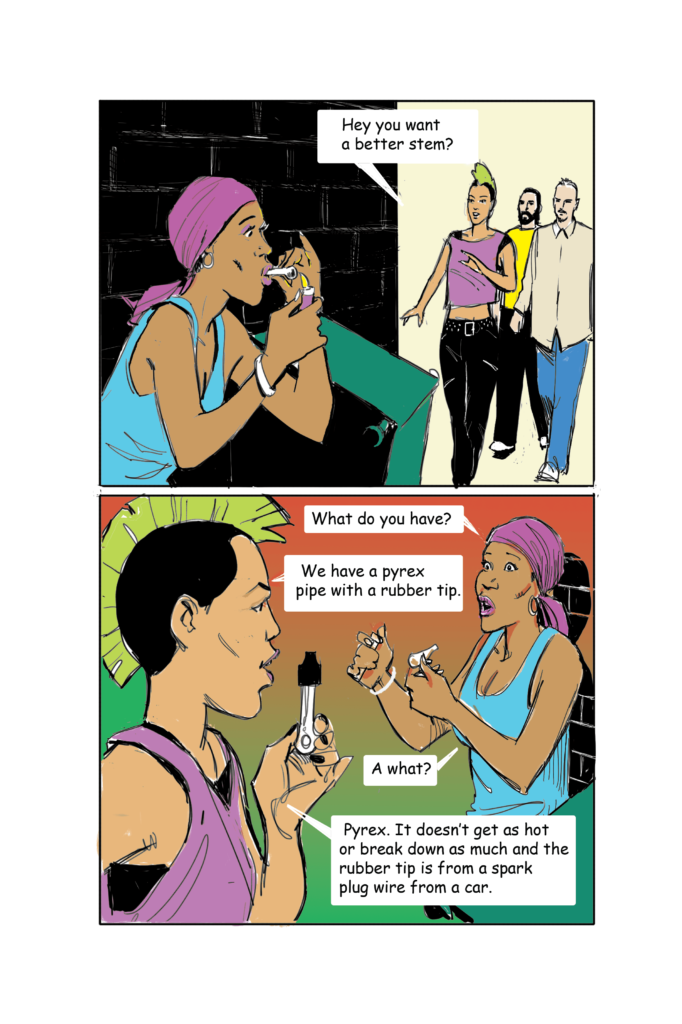

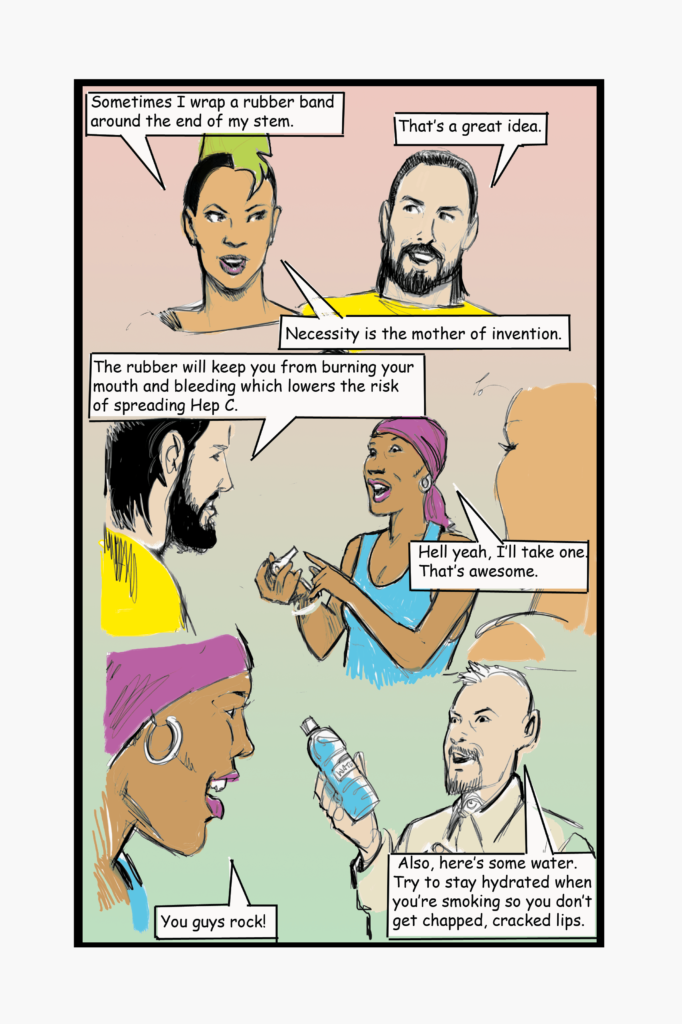

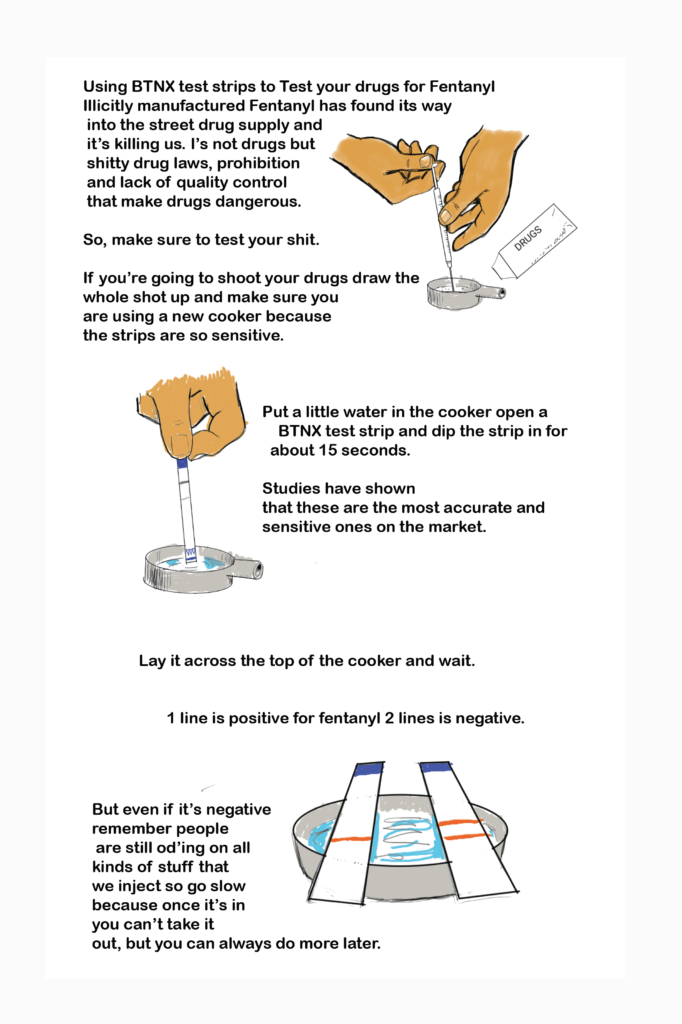

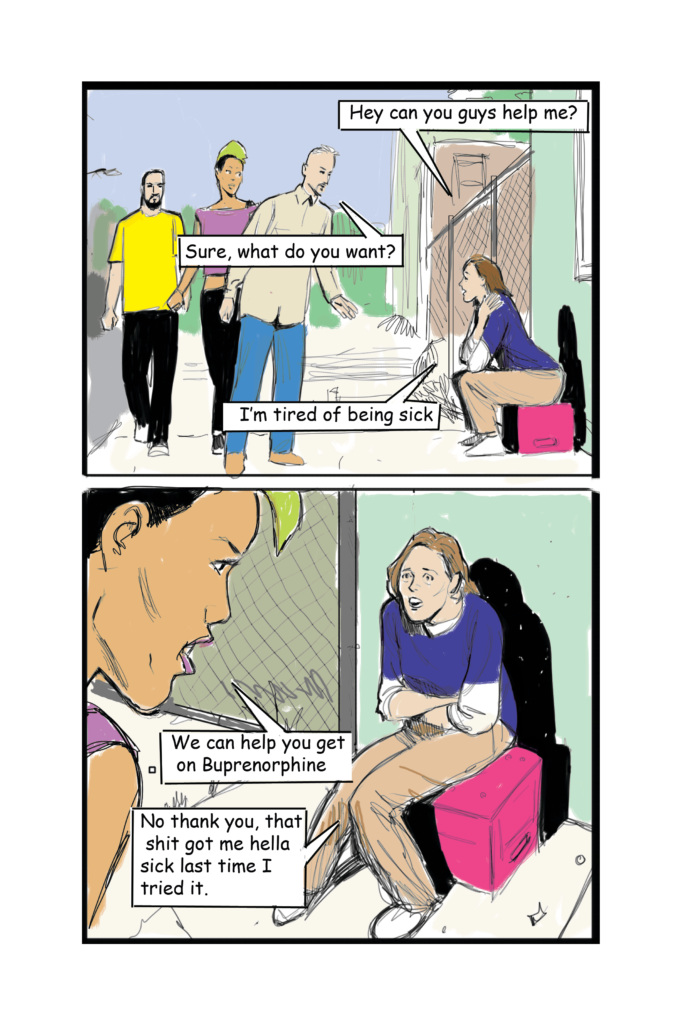

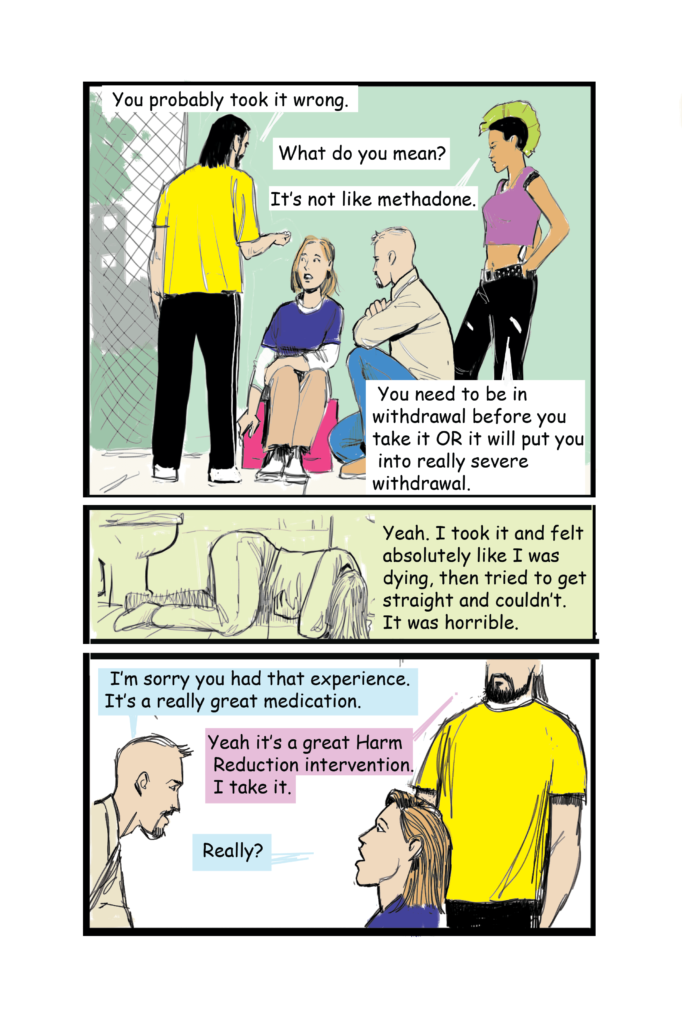

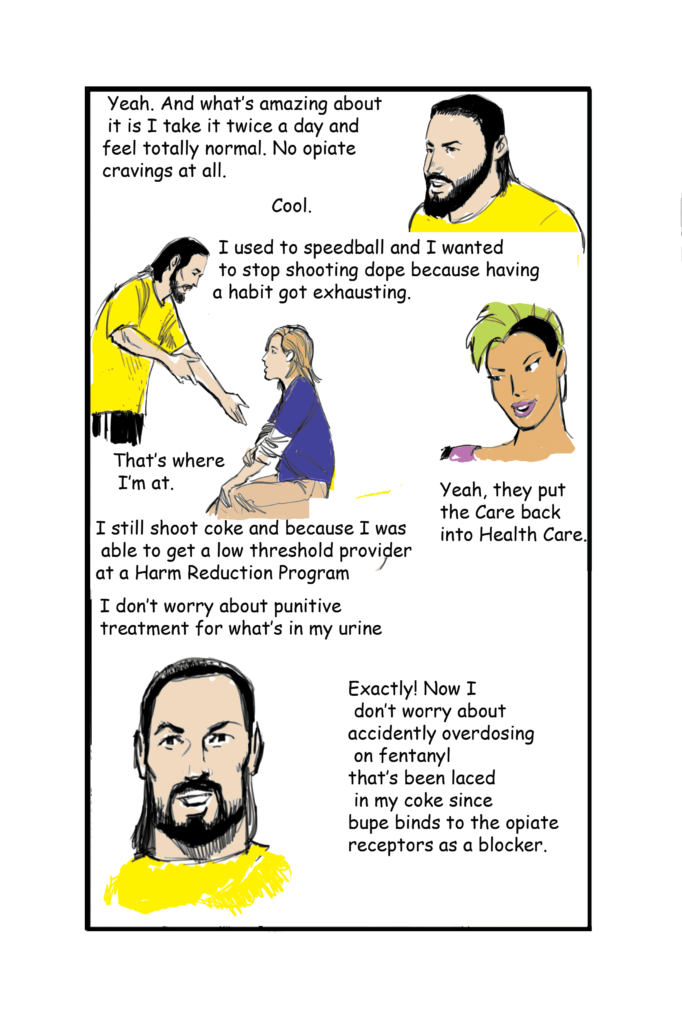

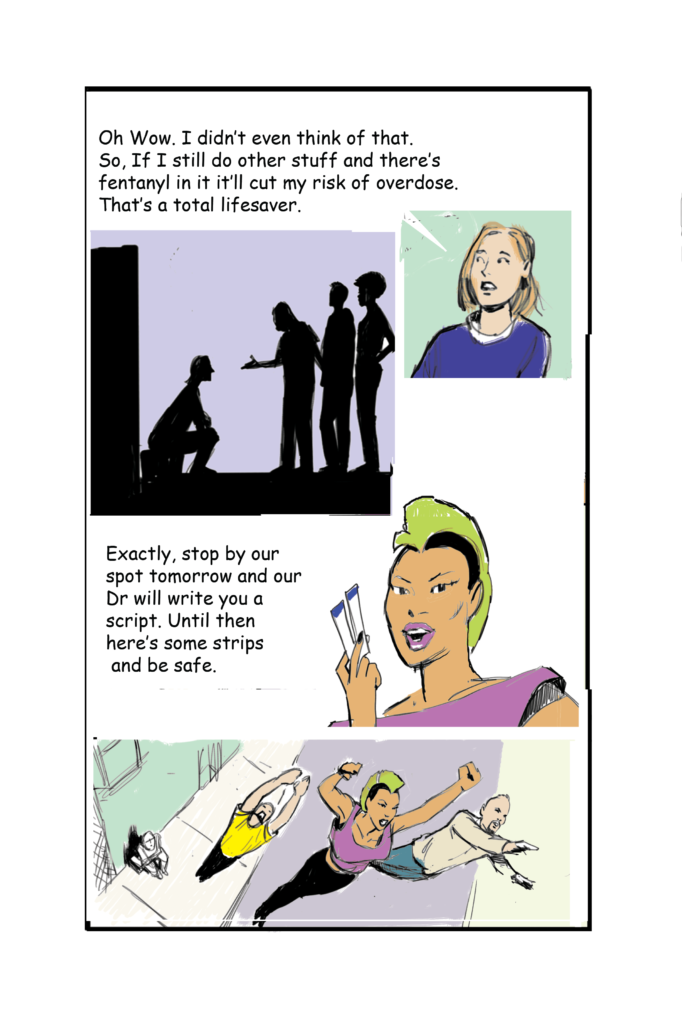

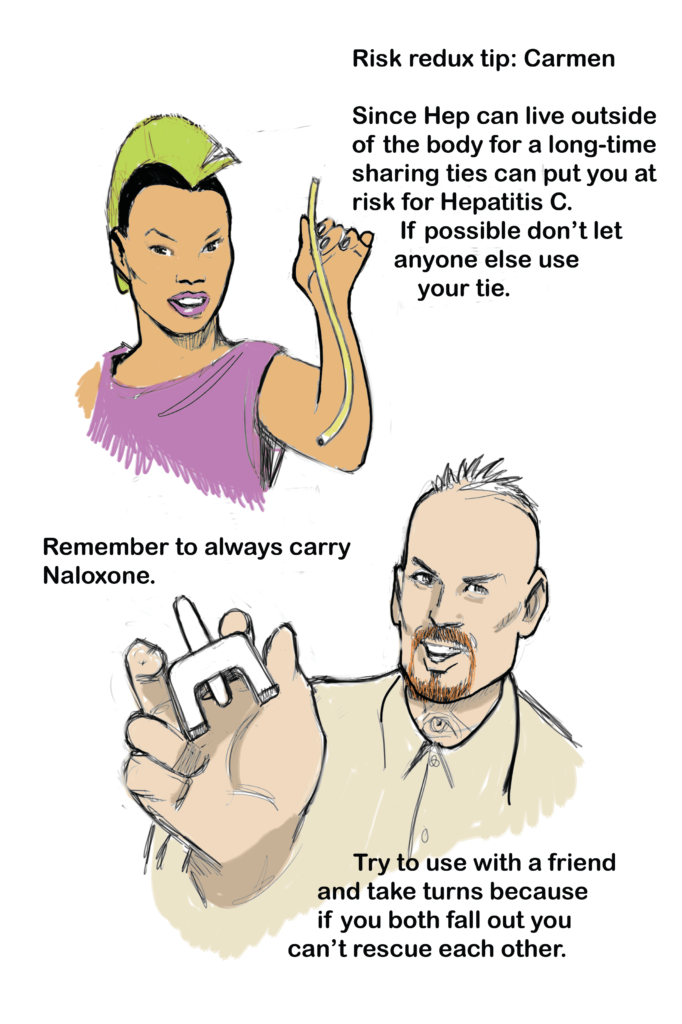

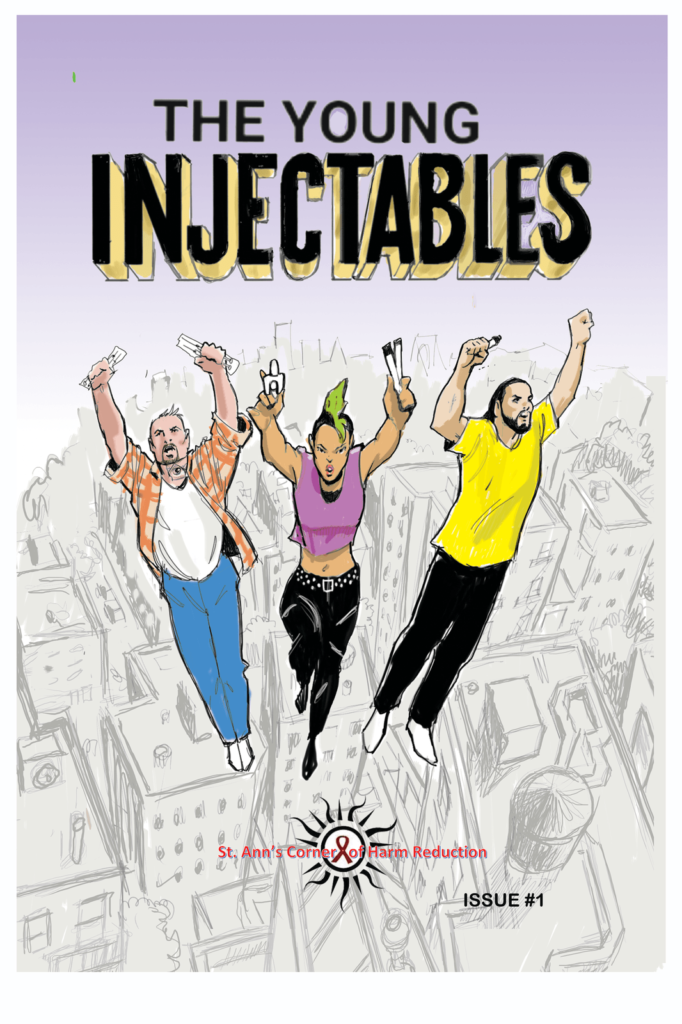

A couple of months ago, I was cleaning off a table in what used to be the drop-in center—before the pandemic—at the syringe service program (SSP) where I work. I still don’t know who left it there, so I never got the chance to thank them, but on the end behind some canned goods and a pile of naloxone that was technically expired but still good was a stapled, black-and-white printout called The Young Injectables. I opened it to find a comic book featuring a trio of harm reductionist superheroes who patrol New York City fighting overdose and stigma and promoting safer use. It came complete with safer injection tips and a tribute to Dan Bigg.

Coworkers eventually helped me contact author Van Asher, who gave me a color copy. Asher, 51, is currently the harm reduction coordinator at Housing Works’ Cylar House. For decades he’s been on the frontlines of harm reduction work around Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the neighborhood where I live and where I first started learning about harm reduction a few years ago through the Lower East Side Harm Reduction Center.

With St. Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction, Asher has made 1,500 copies of The Young Injectables since it came out in 2019. It’s illustrated by his frequent collaborator U.A. Morrison, one of the original guitarists in NYC punk band Murphy’s Law who now lives down in Brazil. Asher’s own artwork is prolific, ranging from professionally cut video to Scotch-taped zines of HIV and hep C info for SSP participants.

A personal favorite of mine is a postcard circa 2000 of a Barbie doll injecting her arm captioned “This Woman is a Role Model / She’s Using a Sterile Syringe.” If you turn it over, it reads: “There has never been one documented case of HIV from a sterile syringe / If you inject, please contact your nearest needle exchange,” followed by the contact info for the handful of SSPs that existed around the city at the time. He’s produced some 150,000 copies.

The Young Injectables has been reprinted in full below, along with excerpts from his stories as we took a long walk around the neighborhood and he talked about the ways it—and harm reduction—has changed.

Asher: I moved into this neighborhood in 1989 and moved out in ’06. I lived down the block [from what’s now Housing Works] when I was a squatter in the early ’90s. It was a time when the building didn’t have running water, and it was a time when people didn’t have personal computers. So we found someone with a printer and printed a fake work permit, and then we rented a jackhammer and dug into the street and tapped into the city water main and illegally routed water to the building. It was that kind of radical work. It was a different world.

When they started building [Cylar House] and I found out that it was residential AIDS housing, and I was working in the field already, I went to a house meeting at the squat and said, “Hey guys, don’t steal building supplies from the corner of 9th and D, it’s gonna be residential AIDS housing. They’re gonna be our allies. But, they’re building a co-op between 10th and 11th, let’s fucking steal their shit for sure because they’re gonna be the next wave of gentrification that’s gonna get us evicted.” And that’s basically what happened.

Harm reduction was very different back then. The Lower East Side exchange was on Avenue C between 3rd and 4th, in a bodega that used to be a coke spot that had gotten busted and then rented out. We took over another bodega that sold coke that got busted in 1992—that was the first exchange in the US to have a storefront. The first federal study came out of there, to show that it worked—which is something that we already knew, because they’d done it in Europe.

We were doing 1 million syringes a year. It was a small staff initially. The first staff person who was paid was Henry Vera, the case manager. There was Mark Geese, who recently passed away. Alan Clear, who was the ED. Raquel Algarin joined shortly after; she passed away two years ago. Mark Gilliam, Dan Raymond. Vicki Jacobson and Linda Williams were acupuncturists.

We did a lot of stuff that wouldn’t fly today. I remember we did a fundraiser and raffled me off. I went on a date with the person and then they wanted to go out with me again, and I was like, “You didn’t buy the boyfriend experience, you bought a date, but thank you.” We did a safer injection training where someone cleaned a set of works and drew up a shot of heroin and then injected and talked through the process and it was like, that was harm reduction. That wouldn’t happen today. People would freak out.

I suspect that street-based sex work is starting to pick up around here [since COVID]. I want to start doing nighttime sex-worker outreach again and just see what’s going on. In the mid-90s there were established strolls back here. There used to be strolls on Pitt St and between 11th and 12th on 3rd Ave. I did outreach all the way down to East River up to 23rd St, but that was different up there because that was a pimp stroll, so it wasn’t safe for me to be out there because now I’m encroaching on someone’s territory.

But three nights a week I’d go out from 10 pm to 2 am and wander about looking for people, on my motorcycle alone or with my dog. I’m still in touch with quite a few of the women I did outreach to. We never know the full impact that we have doing outreach. There are so many stories that we never hear. I wish we would lose the term “harm reduction” and just call it common sense.

On New Year’s Eve 2000 we stayed open from 2 pm to 2 pm. I bought cases of Cold Duck champagne and we had a syringe and champagne party and a Cheech & Chong movie marathon. I got pizza and plastic champagne flutes and we put syringes in them and were handing out syringes and champagne. The AIDS Institute, the state department of health, yelled at me because, “You’re enabling people!” And I said, y’know what, if I ever go to an AA meeting and someone’s like, “I used to put needles in my neck and then this guy handed me a flute of champagne on New Year’s and then I realized I had a problem,” I’ll apologize. What I’m doing is treating people like decent human beings and providing safety.

I’d get fired today for doing something like that.

All photographs courtesy of Van Asher

Show Comments