On August 2, Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney announced that city police will no longer be able to arrest people who possess or distribute fentanyl test strips. He justified his move in an executive order: “We gain nothing by penalizing the distribution and use of fentanyl test strips, which are proven to help people assess and reduce their risk of overdose. Fentanyl test strips are a life-saving tool that we encourage people to have, use, and share with others.”

Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro also backed the policy, stating that his office would not prosecute simple possession of fentanyl test strips. Earlier this year in March, Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner’s office also adopted a policy of not prosecuting possession or distribution of the strips.

All this is critical, as over 1,200 people died from overdose last year in Philadelphia. A vast majority of those deaths, 81 percent, involved fentanyl, which has been detected for years in supplies of various unregulated drugs in the city. Philadelphia’s fentanyl-involved deaths have increased rapidly, from just 9 in 2012 to 979 in 2020. Deaths are also increasing faster among Black and Hispanic residents, according to official data.

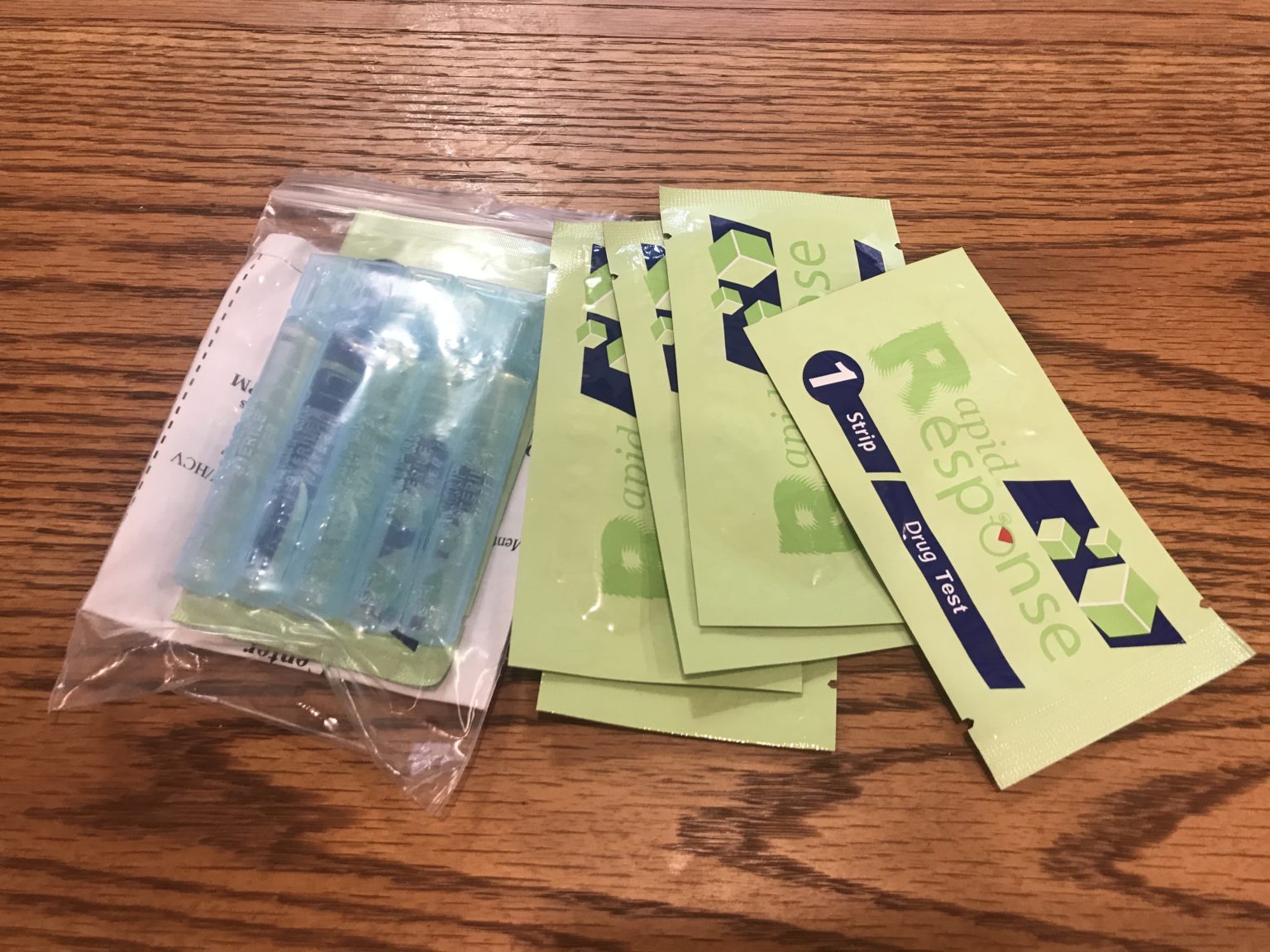

A fentanyl test strip, quite simply, allows you to find out more about what you’re taking. It’s easy to use, and small enough to go in your pocket. You mix a small sample of your drug in a capsule with sterile water, then insert the strip. In minutes, it tells you if fentanyl is present. It works for heroin and other opioids, and for other drugs supplies in which fentanyl is increasingly found, like cocaine, methamphetamine and benzos.

While it tests for the presence of fentanyl, a strip doesn’t tell you how much is in your drug. Another limitation is that it won’t identify every different analog of fentanyl: A 2021 study showed that strips can detect most but not all of them. Despite the limitations of these tests, their basic efficacy and praticality means they can save many lives.

“Places throughout the city that were hesitant to carry them now will feel comfortable doing so.”

Mary Craighead, the overdose prevention coordinator for Prevention Point Philadelphia, told Filter she thinks it’s unlikely the city has actually been arresting and charging people for fentanyl test strips. But that doesn’t mean Mayor Kenney’s move is purely symbolic—quite the contrary. Because previously, the murky legality of fentanyl test strips had a chilling effect on their use.

“When we talk to people who use drugs,” she said, “we tell them we have this tool we encourage them to use every time to test their batch, but please be advised this is technically considered paraphernalia. For people who are impacted by the War on Drugs and may be on probation or parole, they may not feel comfortable carrying them.”

The executive order should take that fear away for everyone. It will make it easier for people to learn about fentanyl test strips and spread them as widely as possible.

“The city is now doing an outreach campaign [about] fentanyl test strips,” Craighead said. “So we’re able to distribute them on a larger scale. And other places throughout the city like doctors’ offices, harm reduction organizations, or [buprenorphine or methadone] clinics that were hesitant to carry them now will feel comfortable doing so.”

This also comes at a time when federal lawmakers have lifted—or are considering lifting—certain restrictions on drug harm reduction. In April, two federal health agencies announced that federal funding can now be used to purchase fentanyl test strips. Filter also reported recently on a draft Congressional budget that would finally end a federal ban on funds used to purchase sterile syringes.

Photograph by Kastalia Medrano

Correction, August 5: This article has been edited to correct Mary Craighead’s job title.

Show Comments