Mutual aid organizing is experiencing something of a renaissance amid the coinciding crises of COVID-19 and overdoses. But the concept is not just used by communities setting up fridges stocked with free groceries or grassroots safer use supplies distribution.

The cops are—and have been—deploying the framework first popularized by a Russian anarchist to facilitate their war on drug users and border communities. While community organizers tend to think about mutual aid as a means to survive and build power despite austerity, law enforcement has defined it as sharing intelligence, pooling militarized equipment, and bringing together officers to boost each departments’ respective capacity to criminalize Black, Indigenous, migrant, and poor communities.

As the movement to defund law enforcement grows and President Donald Trump’s migrant concentration camps continue, law enforcement mutual aid arrangements are now being proposed by sheriffs as a mechanism for ramping up border policing and raising funds through asset forfeiture.

In a federally-funded August 18 report, the National Sheriffs’ Association (NSA) put forth a vision of border sheriffs mutually banding together to increase traffic stops, which often involve racist profiling and have resulted in the murder of Black motorists. Called criminal interdiction units (CIU), these multi-departmental collaborations share information and gather intelligence among sheriffs, which, historically speaking, are nothing new. Since at least the 1960s, some local jurisdictions in states like Wisconsin have had such mutual aid systems for traffic policing.

What seems to different is their function in this current moment. CIUs would address, the authors suggest, border sheriffs’ reported “main priority” of funding, while also supporting efforts to fill personnel voids, bolster northern border policing and crack down on the drug trade—issues and priorities identified in roundtable discussions funded by a Justice Department grant to the tune of more than $100,000. The grantor, the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, did not respond to Filter‘s request for comment about NSA’s report.

The NSA authors, whose spokesperson also did not respond to comment, frame the scaling up of traffic stops as cash cows for law enforcement departments that are at the center of coinciding political battles over defunding the police and Trump’s border regime.

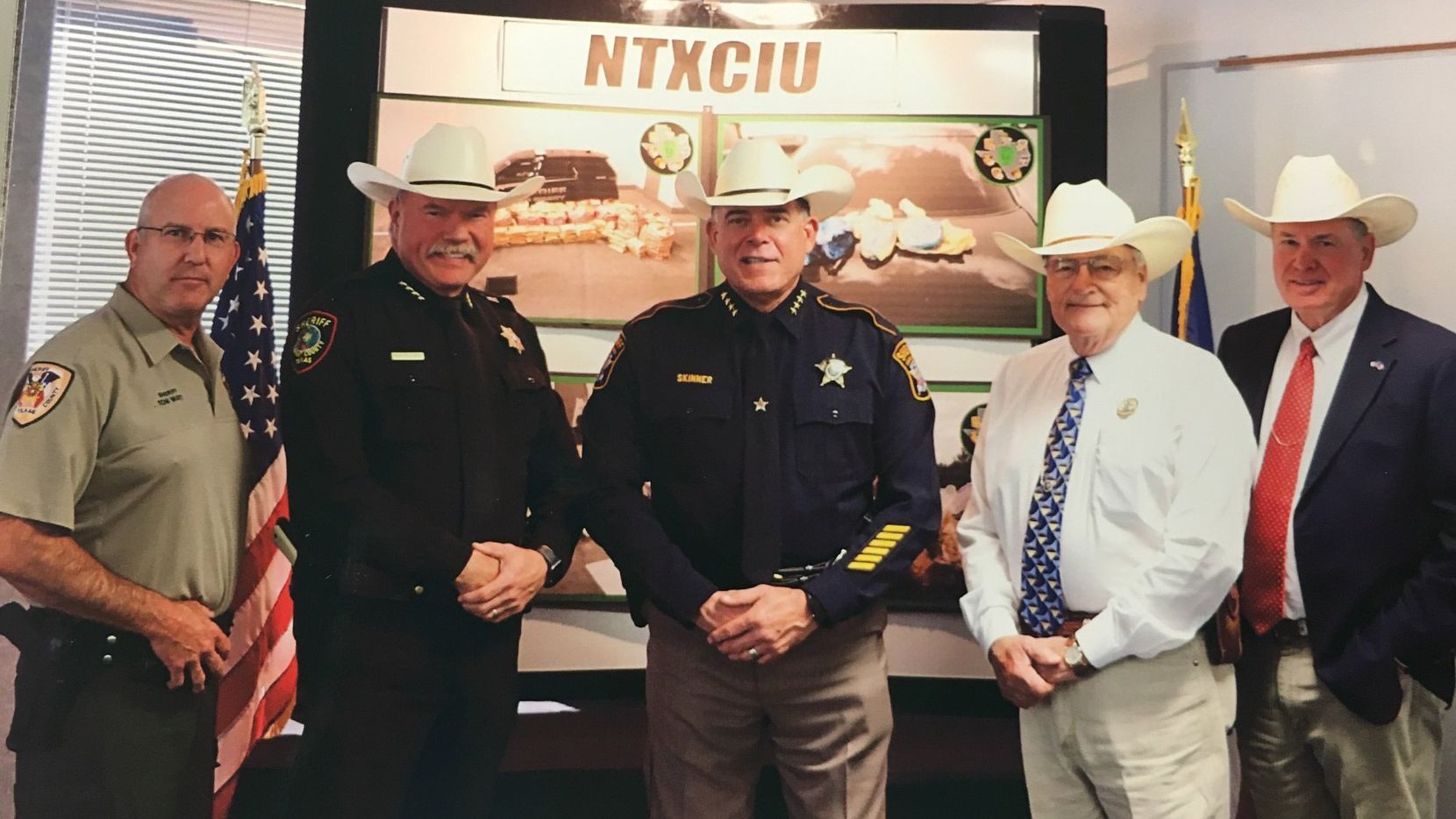

“The value of interdiction units is illustrated” the authors wrote, by a mutual aid model in northern Texas, “which collected more than $65 million in profits from seized illicit substances and weapons in a 30-month period” between December 2017 and June 2020. Cannabis, a plant increasingly legalized despite continued federal criminalization, was the second most common drug seized (more than one-quarter) during arrests, just behind methamphetamine.

The law enforcement organizations know that a coordinated “mutual aid” effort is going to attract scrutiny from progressives and the media.

The collaboration, named the North Texas Criminal Interdiction Unit, “anticipate[s] even better results”—meaning more arrests, and more money taken out of the pockets of communities—with this year’s integration of license plate reader technology in the eight participating counties.

The law enforcement organizations know that a coordinated “mutual aid” effort to ramp up traffic stops along the borders is going to attract scrutiny from progressives and the media, as Trump systematically violates migrants’ human rights and cops brutalize communities. In the words of the report’s authors, CIU members will be in “a high-profile position and will often be the targets of numerous complaints because of their high level of stops and interactions.”

An historic proportion—about one-third—of the public and high-profile cultural figures, like musicians John Legend and Lizzo and actors Jane Fonda and Natalie Portman, support defunding law enforcement. The movement sparked by the police murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Tony McDade has been estimated by The New York Times to be the “the largest movement in the country’s history.”

Bullet-proofing the program from anticipated popular criticism, for the authors, means weeding out the bad apples. “If the wrong member is selected, the unit could fail. The members must be of high moral character, must be highly motivated, and must have demonstrated a high conviction rate. The personnel selected will have the ability to affect all criminal interdiction efforts across the nation through resulting case law—good or bad.”

A Long, Disturbing History

In the United States, law enforcement mutual aid has been used to facilitate settler-colonialism, suppress Black resistance, and stop liberation movements.

It began at least as early as the 19th century. Before local police departments were formed, a 1973 NSA report on law enforcement mutual aid explained, “local U.S. Army troops” would “assist” sheriffs in enforcing United States’ colonial law during “western expansion”—a euphemism for the genocide of Native Americans and theft of their lands.

A century later, law enforcement mutual aid was used to violently suppress Black-led uprisings in the 1960s, from the 1965 Watts Riot, a response to police terror, and the April 1968 actions in the wake of the assassination of Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. After the Long Hot Summer of 1968, Congress passed the 1968 Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act, leading the Department of Justice to commission numerous studies on expanding the country’s “riot control” capacity.

One such report, published in June 1973, recognized law enforcement mutual aid as a “major step” for “control[ling]” public demonstrations, or what they dub “collective violence,” by political activists, students, “urban minorities, especially urban blacks,” and labor unions. Such systems should target, the 1973 document suggests, “housing projects,” “college student unions” and “labor picketing,” among others.

In the 21st century, law enforcement mutual aid systems have been repurposed for the priorities of the ever-militarizing police forces. Post-9/11, they were promoted by the International Association of Chiefs of Police as a model for the domestic War on Terror. Now, amid the 2020 uprisings against police terror, the systems have been activated by local authorities to “protect residents and businesses” in Sacramento, California, among others.

Photograph of sheriffs from the North Texas Criminal Interdiction Unit via Collin County Sheriff’s Office/Public Domain

Show Comments