Missouri Governor Mike Parson (R) signed Senate Bill 678 on June 27 to increase the minimum funding level for the Kansas City Police Department (KCPD): from 20 percent up to 25 percent of the city’s general fund. Missouri voters will be able to approve or reject it in the November election.

If you’re wondering why Missouri gets to determine Kansas City’s police budget, it’s because a state board has controlled the department since 1939, in a situation that’s unique among major US cities. At the time, this was intended to rein in corruption—a local political operator had been deflating police wages so he could exert more influence through bribes. Now, however, it serves to block reforms and budget cuts that Kansas City residents may want.

The controlling Board of Police Commissioners comprises Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas (D), but also four members who are appointed by the governor.

“The governor we elect as a state rarely mirrors who Kansas City votes for.”

“They’re [beholden] to a governor who tends to be either a Republican or a moderate Democrat,” Lora McDonald, executive director of the Metro Organization for Racial and Economic Equity (More2), told Filter. “The governor we elect as a state rarely mirrors who Kansas City votes for.”

The board members “live in a very concentrated wealthy community and not in an area that’s overly policed,” she added.

For More2 and other community organizations, establishing local control would be a step toward holding officers accountable for abuses.

“In terms of the citizen body count here, nothing’s changed at all,” McDonald said. “In fact, it’s probably gotten worse in the past few years … there’s a pattern of officers who’ve committed multiple offenses who not only stay on the force; they get no discipline whatsoever.”

Kansas City advocates and protesters, like those in many other US cities, put renewed pressure on lawmakers to enact policing reforms after the May 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. In June 2020, following several nights of protests, Mayor Lucas signed a list of demands presented by community leaders. They included creating a community review board to oversee police, regaining local control over the department, and requiring all officers to wear body cameras.

The following year, advocates criticized the city’s progress as too little, too late. In April 2021, a coalition of seven organizations released additional demands to the mayor and police. These included the dismissal of then-Police Chief Rick Smith (Smith, who was criticized for his response to Black Lives Matter protests and the police killing of 26-year-old Cameron Lamb, a Black man, stayed on, but retired earlier this year). They also demanded that the police budget be reduced to no more than the 20 percent of the city’s budget required by state law.

In May 2021, Lucas and the City Council approved a plan to reallocate $42 million from the $239 million police budget. The police would remain funded at 20 percent of the city’s budget; anything above that would be controlled by the City Council and go into a “Community Services and Prevention” fund.

But a Jackson County Circuit Judge struck down the plan in October, ruling that it unlawfully stepped over the state’s authority to set the police budget. The city attorney had pointed out that Kansas City police have changed their own budget 65 times in the last 10 years.

McDonald explained the rationale behind these efforts. “Here we have a [state] law that requires 20 percent already, and a city council that’s been allocating more like 25 percent of the budget for decades to the police department,” she said. “Really they were just saying: That extra 5 percent, we want to have some say, because we don’t have to give you that by law.”

“The bill violates the Missouri Constitution and will be challenged in court,” Mayor Lucas wrote.

But Republican politicians didn’t like the idea of the city having more say over its police budget. State Senator Tony Luetkemeyer (R) introduced Senate Bill 678, to codify a police funding increase into law, which is how we got to this point.

A lawsuit now seems likely. “The bill violates the Missouri Constitution and will be challenged in court,” Mayor Lucas wrote in an official statement. He seems to be referring to the Hancock Amendment, a 40-year-old law that restricts the state government from mandating local-government funding increases.

The mayor, it should be noted, is no Defund-the-Police activist: He argues that he opposes the state’s control because he wants to support police. “Since myself and the City Council took greater control of police budgeting, officers have received pay raises, new recruiting classes have begun, and officer morale has increased,” he said.

But voters statewide will have the final say, for now. As a proposed constitutional amendment, the funding increase will be put to them on November 8. A partisan breakdown of legislature support for SB 678 may offer a hint of what to expect: It passed both chambers with pretty overwhelming Republican backing and Democratic opposition.

So for Kansas City to take control of its own police budget, it will heavily need votes from other Democratic-leaning cities like St. Louis and Columbia, in a state that broke for Trump by a 15 percent margin in 2020.

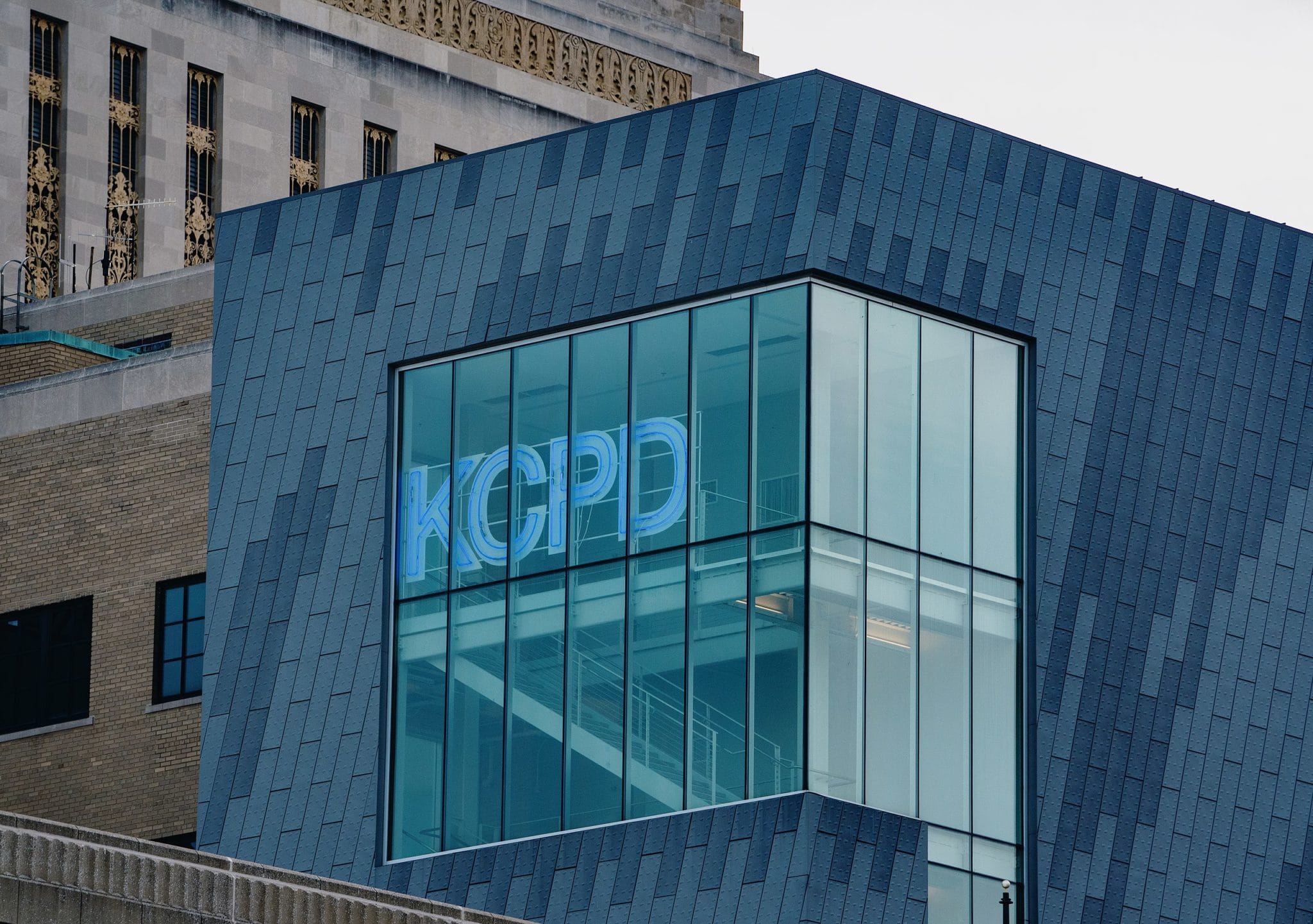

Photograph of KCPD headquarters by Tony Webster via WikiMedia Commons/Creative Commons 2.0.

Show Comments