What I remember most about precipitated withdrawal last year is the color yellow. It was like living the gruesome, nightmare version of a Coldplay song: I puked and shit, I emptied my intestines from end to end, and it was… all yellow.

Pungent, bitter, mustard-yellow liquid spluttered out of me on-and-off for hours, coupled with full-body chills and an overwhelming anxious fatigue. Less intense variations of these symptoms lasted intermittently for the next two days. When I could finally trust myself to be a few feet from a toilet for longer than a couple minutes, I curled into a sad, sweaty ball beneath a bundle of covers, cuddling a plastic shopping bag in case I needed to spew any more yellow bile. The color still makes my stomach muscles clench.

It wasn’t my first time taking buprenorphine. I knew it was important to wait until enough time had passed since my last use of a conventional opioid, in order to avoid precipitated withdrawal. After years of safely balancing regular heroin use with occasional buprenorphine in my early twenties, followed by years of buprenorphine-based recovery—with a couple slips and more than one successful induction—I wasn’t at all worried about re-starting.

But one major change had taken place in the illicit market since my previous time starting bupe from active use: the spread of fentanyl, which was definitely present in the heroin I was using—I tested positive for it at the clinic where I received my buprenorphine.

Still, I always thought of fentanyl as a short-acting opioid, and online guidelines gave me the impression that waiting 12-to-24 hours was long enough. But even though I waited more than 24 hours after my last use, counting enough withdrawal symptoms to score above a five on the COWS Scale, I still experienced that horrorshow.

“The usual opiate withdrawal symptoms but multiplied by 100, and they came on at once.”

I’m not alone. Keith, who asked that only his first name be used, told me that he tried buprenorphine a few years ago, while he was addicted to illicit fentanyl. He had purchased the bupe on the street, and knew that it could induce withdrawal if taken too soon. But he’d also been told he could use it to get through a day when he couldn’t get dope.

About 24 hours after his last fentanyl use, he took a “tiny piece,” then a few minutes later topped it off with a bit more, totaling what he thinks was about three or four milligrams. Within 20 minutes, he said, he “knew what precipitated withdrawal was.”

He described it as “the usual opiate withdrawal symptoms but multiplied by 100, and they came on at once … very bad stomach symptoms, diarrhea, extreme fatigue, restless [and] cramping legs, extreme hot flashes and sweats followed by chills, watery eyes, sneezing, [and] nausea.”

What’s Happening Chemically

Buprenorphine generally requires a brief period of opioid abstinence before patients can begin taking it. It’s a potent chemical, but is only a partial opioid agonist—it only partially fills the brain’s opioid receptorsl. Because buprenorphine is so strong, however, it will “knock” other opioids out of the receptors, essentially performing a chemical coup.

“You very quickly go from a full opioid effect to a partial opioid effect, and that’s called precipitated withdrawal,” explained Pouya Azar, an addiction medicine physician at Vancouver General Hospital’s complex pain and addiction services department.

But now that fentanyl has saturated the North American illicit opioid market, physicians have been finding it harder to get patients started on buprenorphine using conventional induction methods. Experiences like those Keith and I endured are becoming more common: Patients are waiting a full day or longer, feeling the onset of withdrawal before taking buprenorphine, and still going through precipitated withdrawal.

Turns out, there’s a reason for that. Fentanyl is lipophilic, which means it stores in fat cells.

“In heroin times, patients would come in withdrawing. They’d come in the clinic and get their buprenorphine,” recalled Rupinder Brar, a primary care physician with the PHS Community Services Society in Vancouver, Canada, and an addiction medicine research fellow with the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use. But after fentanyl became prevalent, “they’d stop using overnight, come in withdrawing, and still have precipitated withdrawal. It wasn’t making sense.”

Turns out, there’s a reason for that. Fentanyl is lipophilic, which means it stores in fat cells. Marijuana users might recognize that property from tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive component in cannabis, which is notorious for showing up in drug tests well after the last use. The fact that it’s lipophilic causes it to stay in someone’s system long after they’ve stopped feeling the effects. The same applies to fentanyl.

“Fentanyl is a short-acting opioid, but it sticks in the fat so much [that]… it accumulates if you use it regularly and consistently enough,” explained Brar. “For people who have an opioid use disorder and who obviously need to use this opioid many times a day, it becomes a long-acting opioid in their body.”

There’s another complication: Illicitly manufactured fentanyl is not the same stuff researchers or ICU doctors are used to, an issue created by the criminalization of drugs. The unregulated fentanyl that ends up in a dope baggie is often produced in makeshift labs with janky equipment. Manufacturers are constantly looking for ways to cut corners and increase profits, and aren’t concerned with fluctuations in the formulation of their product.

“Fentanyl is an interesting molecule,” said Azar. “There are a lot of fentanyl analogues in the illicit market and I’m not sure we know what all the analogues are. They all act differently, and they potentially act differently than the pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl we are used to.”

Essentially, knowing how long a hit of street fentanyl will remain in someone’s system has become a guessing game.

In Vancouver, British Columbia, like many parts of the United States, fentanyl has virtually replaced heroin in the street supply. This means that patients seeking treatment for opioid use disorder are often coming in with dependencies on fentanyl analogues that their physicians may have never encountered. Pharmaceutical fentanyl is a short-acting opioid, but analogues can be much longer-acting. Essentially, knowing how long a hit of street fentanyl will remain in someone’s system has become a guessing game.

“We are kind of in an unprecedented time when it comes to addiction medicine and opioid use disorder,” said Azar, “just because we are dealing with opioids that are new and we don’t necessarily have a good understanding of their pharmacology.”

Developments in Buprenorphine Microdosing

Thanks to a relatively new method of buprenorphine induction, however, patients can start the evidence-based treatment without experiencing any withdrawal at all.

The method utilizes buprenorphine microdosing. In the simplest terms, patients concurrently take teeny-tiny doses of buprenorphine along with a full agonist opioid, like prescription hydromorphone (although in the US, where doctors aren’t allowed to co-prescribe buprenorphine and morphine for addiction, patients have no option beyond street supplies).The buprenorphine doses under this methodology are as as low as .25 mg at onset—too low to displace enough of the other opioid to cause precipitated withdrawal.

Over time, the buprenorphine dose is gradually increased to create a baseline level that keeps the patient from experiencing withdrawal. That way, once the full agonist is removed, the patient’s opioid need is still maintained on buprenorphine.

The first buprenorphine microdosing approach, dubbed the Bernese Method, was developed in 2010, with subsequent research on the method published in 2016. It initiates buprenorphine withdrawal-free over the course of nine days. Patients taper down on their full agonist, like methadone or heroin, while increasing doses of buprenorphine.

Although physicians in Europe saw success with this, physicians in North America were encountering problems. Brar, for example, said she didn’t have access to the doses required by the Bernese Method. Azar was finding that this method simply took too long to be utilized effectively in the hospital setting.

She said the use of microdosing for buprenorphine inductions has generally been “wonderful.”

In January, Brar published a seven-day microdosing schedule that starts with a .5 milligram loading dose, a dosage available to her and her colleagues. She said that they use a more rapid process for inductions completed in the hospital, and that the use of microdosing for buprenorphine inductions has generally been “wonderful.”

She mentioned that some of her patients reported mild symptoms of withdrawal, such as “a bit of sweating or anxiety at day three or four,” but overall she’s noticed “the desirability of Suboxone [treatment] increased” with the application of this method.

Azar, who has also published literature on microdosing, said that it is now the standard of care at his clinic, and that they have been able to complete withdrawal-free inductions in as little as 48 hours.

“We know that the duration of action of buprenorphine is dependent on the dose, so when you give very, very tiny doses, if 12 or 24 hours goes by in between these doses, you’re not really stacking the dose,” he explained. “So I did my dosing schedule based on time to max serum, which means the time it takes to get maximum levels in the blood, which is about one to three or four hours, depending on the person.”

“I dose [buprenorphine] every three hours to be able to rapidly build the [buprenorphine serum blood] levels in the body without causing precipitated withdrawal,” he continued. “At the same time, I very aggressively will give them hydromorphone … The key with hydromorphone is to meet their opioid requirements, so they are not in withdrawal, and they are comfortable while the buprenorphine is being built up. Usually by 48 hours they are at a good dose of buprenorphine.”

Azar called this method of microdosing “a game-changer for hospital medicine,” and even revealed that he and his colleagues have now “developed an even more rapid induction protocol, pending publication.”

Prospects for Wider Application

Anyone familiar with the intense scrutiny and stigma placed on opioids in the US should immediately recognize why such methods haven’t taken our addiction treatment scene by storm. Imagine the reaction of an abstinence-based provider—accustomed to forcing people to strip down and pee before their eyes—to being told they should now prescribe morphine to their patients alongside their buprenorphine, even if just for a few days.

Azar also suggested that the widespread implementation of this method in the US might be hindered because there have not yet been randomized controlled trials, making microdosing an off-label use—and, as he noted, “the United States is much more litigious.”

Addiction medicine is poised in an unusual moment right now. Providers are being forced to weigh the benefits of surveillance against the need for infection control as efforts continue to stem the spread of the novel coronavirus. Some have made better choices than others. Surprisingly, the DEA, notorious as the vanguard of the US drug war, made at least one decision in favor of public health by temporarily allowing buprenorphine to be inducted by telemedicine. This means that more people now have the opportunity to start treatment at home.

Is it safe for patients to try microdosing at home?

Increased low-barrier access to evidence-based treatment is undoubtedly a good thing. But what about the increased risk of precipitated withdrawal posed by fentanyl? Is it safe for patients to try microdosing at home?

“I think they have been doing this, from what I hear, for a while, well before doctors and researchers figured it out,” said Brar when asked.

There is certainly truth to that. When I was younger, before I had any real interest in accessing treatment, I used to take low doses of diverted buprenorphine in the morning so that I could function at work, and then get as high as possible on heroin every night. I didn’t call it microdosing, or think of it as a “game-changer.” To me, it was just getting by—and I’ve spoken with a number of other people who have engaged in similar practices.

The one issue I see, again and again, is misinformation. For example, plenty of people think that because they took a low dose of a buprenorphine-only formulation, or because they took a buprenorphine-only formulation every day and did not experience precipitated withdrawal, that means only formulations containing naloxone will cause withdrawal. That’s not the case (as a side note, I did this with Suboxone, which contains buprenorphine and naloxone).

Buprenorphine alone causes precipitated withdrawal. But as Brar and Azar’s research demonstrates, taking low enough doses, or building upon pre-existing levels of buprenorphine—taking a traditional opioid while buprenorphine is already present—can prevent this.

Still, both physicians say that if you want to try microdosing at home, it’s best to do so under a doctor’s guidance. Azar’s patients are able to receive pre-measured microdosing blister packs, along with doses of hydromorphone.

Patients in the US or who otherwise don’t have access to a prescription microdosing blister pack can still go over the published research with their prescribers and discuss putting together a regimen by splitting their pills or films.

People without prescriptions, or whose physicians won’t entertain a microdosing induction, can read the research on their own. But if they decide to utilize one of the microdosing schedules outlined in the papers, they should be wary that the methodology is new, and far from foolproof.

Brar, for example, noticed that a small subset of microdosing patients reported minor withdrawal symptoms, and some ended up discontinuing treatment. She said these patients were almost exclusively people who had experienced precipitated withdrawal from buprenorphine in the past.

Azar said that “the rate of people who experience precipitated withdrawal through microdosing in hospital, from my personal experience, is almost zero. In the community it’s much more variable, and that really needs to be studied.”

“If anyone wants to try it in conjunction with their prescriber, it’s really worth giving a try.”

He also recommended that any patients attempting buprenorphine induction at home—whether through microdosing or traditional methods—should go to the nearest clinic or emergency department if they end up experiencing severe symptoms of precipitated withdrawal.

When I experienced it, I waited it out, and even delivered a lecture at the tail-end of it—though as awful as my experience was, I had only taken about four milligrams of buprenorphine, and probably still was not experiencing the full wrath of potential withdrawal.

Keith said he was able to score a bag of dope, which brought him close enough to baseline for it to be bearable.

Although buprenorphine blocks the effects of other opioids, it is still possible to overdose when trying to overcome that blocking effect. For people who decide to attempt it anyway, they should utilize basic harm reduction protocols, like having naloxone on hand, and using with someone else present.

For patients who still want to use traditional methods of induction at home, Brar suggested starting with a low dose, like two milligrams, once they are in a state of withdrawal, then waiting an hour or so to see how they tolerate it.

“We need to learn more about microdosing in our fentanyl era,” said Brar. “For now we have case reports published that do show it does work for some. If anyone wants to try it in conjunction with their prescriber, it’s really worth giving a try.”

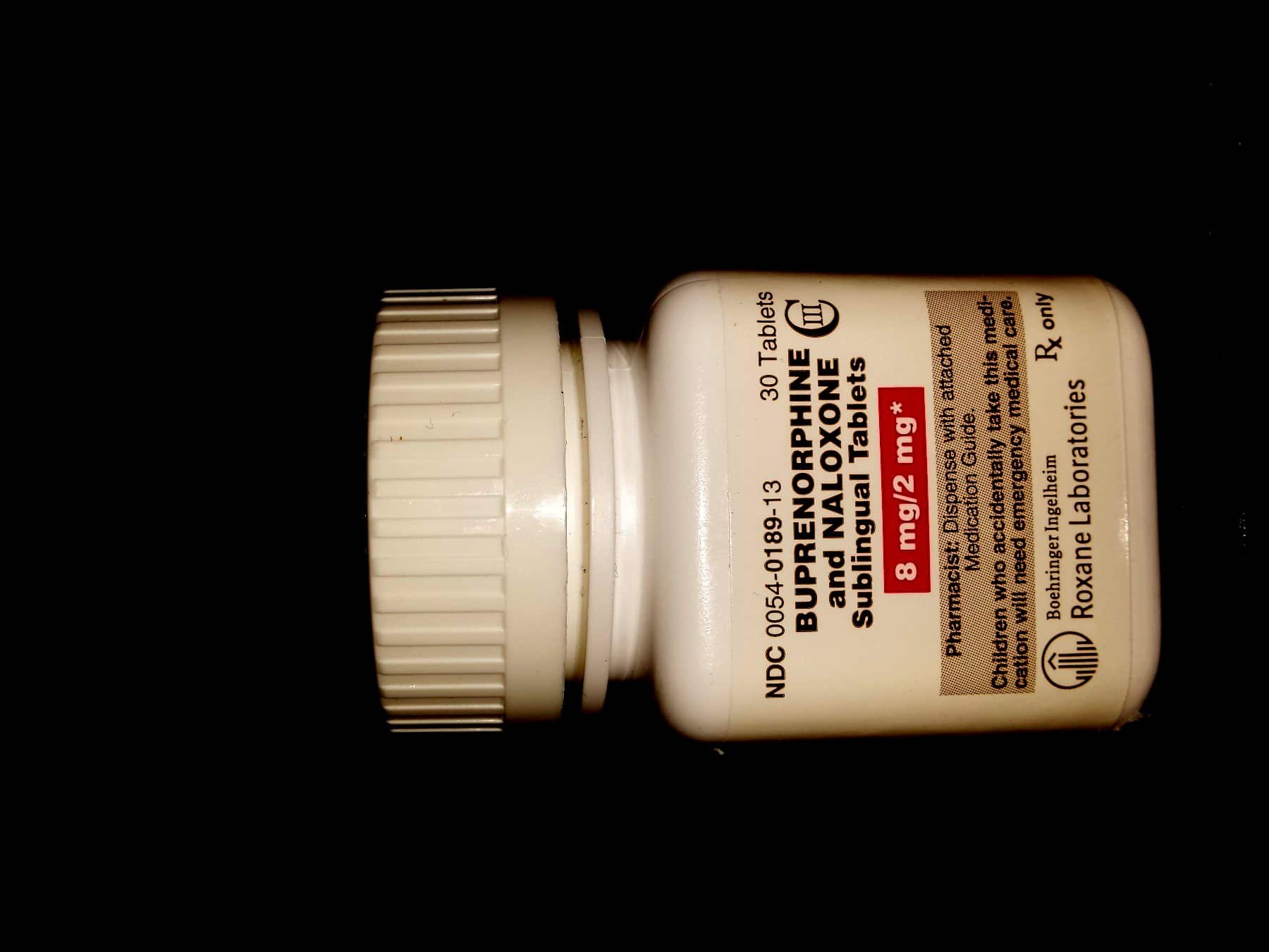

Photo of buprenorphine-naloxone bottle by tmeers91 via Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons 3.0.

Show Comments