The United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania launched a preemptive strike February 6 against what the harm reduction community hopes will become the nation’s first legal safer consumption site—calling on a federal judge to declare a planned SCS in Philadelphia illegal before it even opens its doors.

In a morning press conference that piggybacked on the announcement of indictments against 14 individuals for their involvement in an alleged “pill mill,” US Attorney William McSwain revealed that his office had filed a complaint for declaratory judgment in federal court on February 5. It aims to prevent Safehouse, a nonprofit organization, from following through with its plan to open an SCS in the Philadelphia’s troubled Kensington neighborhood.

“Normalizing the use of deadly drugs like heroin and fentanyl is not the answer to solving the opioid epidemic,” said McSwain, who referred to Safehouse as a “deadly drug injection site,” even though it presently exists only on paper, and its evidence-based goal is to reduce the dangers associated with illicit drug use.

The civil lawsuit (which can be viewed at the bottom of this article) names Safehouse, which was incorporated in August 2018, and its executive director, Jeanette Bowles, as defendants. Bowles served on the Mayor’s Opioid Task Force Harm Reduction and Overdose Prevention Subcommittee before recently taking leadership of Safehouse. According to court records, a summons was issued to Bowles through her attorney, notifying her of the action.

Safehouse coalesced in the months following Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney’s January 2018 announcement that the city would not stand in the way of good-faith efforts to mitigate rising drug deaths in the city, including the opening of an SCS.

Its board comprises heavy hitters in harm reduction, politics and public health—including Jose Benitez, executive director of the Kensington-based harm reduction group Prevention Point Philadelphia; Ed Rendell former mayor of Philadelphia Mayor and DNC chair; Thomas Farley, commissioner of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health; and Ronda B. Goldfein, an attorney and executive director of the AIDS Law Project of Pennsylvania. Safehouse has retained the law firm DLA Piper to represent it as it pursues its plans to make Philadelphia the first US city with a municipally sanctioned SCS.

Safehouse supporters protest McSwain’s move

Safehouse supporters protest McSwain’s move

McSwain Challenges the Extensive Evidence Behind SCS

McSwain’s presentation challenged SCS in Philadelphia on both legal and efficacy grounds.

“Let’s step back for a moment, consider the big picture, and discuss what we really know about injection sites,” said McSwain. “Safehouse claims that an injection site would save lives. But are we sure about that?”

Although research from numerous countries shows SCS help prevent overdose and blood-borne disease, McSwain criticized the city’s reliance on data from Vancouver, where InSite has operated as the only sanctioned SCS in North America since 2003. Calling the positive outcomes there “hyperlocal,” he questioned whether they could be replicated in other cities, like Philadelphia.

“[Safehouse] has no idea whether an injection site in Philadelphia would actually save lives,” McSwain continued. “All they’re doing is speculating and trying to pass it off as fact. They have no proof, no reliable data. There is no expert consensus that this plan would do any good for anybody.”

“The best predictor of an outcome is what happened before.”

Safehouse board member Ronda Goldfein told Filter, regarding on McSwain’s wholesale dismissal of SCS as an effective public health tool, that in lieu of evidence that SCS don’t work, the argument is little more than a red herring.

“The best predictor of an outcome is what happened before,” she said. “We have no crystal ball, but I do think that when we talk about research it’s not enough to say, ‘I don’t think that this research is good.’ Show me some credible research that shows a different outcome and then we can talk about it.”

Gus Grannan, a long-time harm reduction advocate and member of the Philadelphia Drug Users Union, told Filter, “All that tells me is that [McSwain] didn’t bother to read any research that wasn’t in English.”

The Questionable Legal Basis of the Challenge

But ultimately McSwain’s opposition to Safehouse comes down to one factor. “The law is clear, and my job is to enforce the rule of law,” he said. “Setting up a drug house is illegal. And on the legal issues in this case our position has remained firm… Safehouse’s operation would violate federal law.”

The lawsuit states: “For purposes of this action, it does not matter that Safehouse claims good intentions in fighting the opioid epidemic. What matters is that Congress has already determined that Safehouse’s conduct is prohibited by federal law, without any relevant exception.”

The law in question is a subsection of the Controlled Substances Act that prohibits the operation of a premises intended to use illicit drugs. This so-called “Crack House Law” was passed by Congress as part of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 and applies to persons or organizations that “knowingly open, lease, rent, use, or maintain any place … for the purpose of manufacturing, distributing, or using any controlled substance.”

Goldfein confirmed that the group had no prior knowledge of McSwain’s intention to file a request for an injunction against Safehouse, but acknowledged it was preferable to address questions about its legality before the first site, which is planned for Kensington, becomes operational.

“We have consistently maintained that we disagree with [McSwain’s] analysis,” said Goldfein. “There is a fundamental disagreement on a fact of law; but I feel confident in our interpretation and that a judge who gives this consideration on the merits will rule in our favor. We believe that this initiative to save lives is not in opposition to the purpose of the [Controlled Substances Act].”

The Safehouse case has been assigned to Judge Gerald Austin McHugh Jr., an appointee of President Barack Obama and lifelong Catholic who is quoted as saying, “Faith calls upon us to act in certain ways. One of the most important ways for a Catholic is showing concern for the poor.” Advocates expressed hope that he will reflect this in his ruling.

The so-called Crack House Law has been the primary impediment to the opening of an SCS in the US—even as deaths related to fentanyl in the drug supply have skyrocketed—and the subject of in-depth analysis by public health and law experts.

“There’s a good legal argument that the Crack House statute wasn’t intended to, and shouldn’t apply to, a bona fide health operation.”

Safehouse maintains that it is exempt from prosecution under the law because its primary purpose is not simply to give people who use drugs a place to get high, but to medically intervene when necessary and educate participants about treatment options. The organization spelled out that position in a November 26, 2018 letter to McSwain:

“The legislative intent of Title 21, United States Code, Section 856 is to prohibit individuals from knowingly allowing their property to be used for the purpose of distributing or using drugs for profit. We believe that a proper and constitutional application of Section 856 does not prohibit our primary purpose of preventing fatal overdoses.”

Legal scholars have said that there is a gray area in the law that supports this argument, backed up by some precedent.

Writing in 2008 on the legality of “pure consumption cases” under the federal Crack House Statute, Michael E. Rayfield—now a partner in Mayer Brown’s Supreme Court and Appellate practice—noted that while circuit courts have varied on where to draw the line, they “are generally in agreement that the statute covers more than just those defendants who open or maintain facilities solely for the purpose of drug activities, and that the statute does not apply to drug activity that is merely an ‘incidental’ or a ‘collateral’ purpose of the place.”

Corey Davis, deputy director and staff attorney at the Network for Public Health Law, agrees that this argument has merit. “There’s a good legal argument that the Crack House statute wasn’t intended to, and shouldn’t apply to, a bona fide health operation,” he said. “[McSwain] is pre-emptively trying to shut down a public health intervention that’s designed to save lives. That’s not in anyone’s interest, and it’s incredibly heavy-handed.”

This Is Urgent

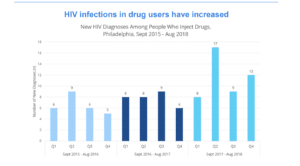

Gus Grannan noted that since 2017, when the City of Philadelphia shut down “El Campamento,” an unsanctioned, popup drug use site in West Kensington that was easily accessible for outreach workers, HIV rates among the city’s injection drug users have begun to inch up, having previously remained steady for years.

This chart from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health demonstrates the point:

It adds local urgency to utilizing the demonstrated ability of SCS to reduce syringe sharing and transmissions of diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C.

It adds local urgency to utilizing the demonstrated ability of SCS to reduce syringe sharing and transmissions of diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C.

According to the Drug Policy Alliance there are about 120 legal SCS currently operating in at least 12 countries around the world, including Canada, Australia and numerous European nations.

The complaint:

show_tempAll photographs: Christopher Moraff

Show Comments