Senators are scrambling to negotiate a last-minute deal on crack cocaine sentencing reform. Current federal law punishes convictions for crack far more harshly than for powder cocaine, and the consequences of this have long been established as racist. Democrats want to remove the disparity completely, while Republicans would just water it down.

Democratic Senators Cory Booker (NJ) and Dick Durbin (IL) introduced a bill to eliminate the current 18:1 crack-powder sentencing disparity just days after President Biden took office in 2020. Dubbed the EQUAL Act, it passed the House of Representatives in September 2021 with a surprising bipartisan majority of 361-66, as numerous Republicans joined a unanimous Democratic bloc.

Over a year later, it now comes down to the Senate. Time is short, with only a few weeks until this congressional session ends on January 3.

The Senate Judiciary Committee remains divided over two points—the disparity itself, and whether changes should be retroactive.

The EQUAL Act could pass as a standalone bill, or be attached to “must pass” legislation. Sen. Durbin confirmed to Bloomberg that Democrats are considering attaching the bill to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which Congress must approve every year to fund the defense department and military. If that option fails, Senators might instead attach it to a package of spending bills to fund the federal government. Congress will need to approve something at least by December 16.

On the crack sentencing issue, the Senate Judiciary Committee remains divided over two points—the disparity itself, and whether changes should be retroactive. Senator Chuck Grassley (IA), the committee’s top Republican, has countered with his own proposal, the SMART Cocaine Sentencing Act. Republicans say it would represent progress by reducing the sentencing disparity to 2.5:1. But the bill also raises powder cocaine penalties: To trigger a five-year mandatory minimum sentence, the current level of 500 grams would be lowered to 400 grams.

Another difference concerns retroactive relief. The EQUAL Act makes anyone with past convictions eligible for re-sentencing. They would have to file a motion in federal court, with relief granted if a judge determines the person doesn’t pose a danger. US attorneys’ offices could object. But in Grassley’s SMART Act, retroactivity is more severely limited, as the attorney general would have to review and certify each case. As a result, many people might be denied re-sentencing. Senators could even decide to remove retroactivity completely, according to Politico.

Kevin Ring, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM), told Politico that it would be “immoral to pass a bill that did not provide relief to those whose sentences were so bad that it convinced Congress to change the law.”

The politics on this issue have changed dramatically in the past few decades. For example, Joe Biden—both as a candidate and as president—has come to oppose some of the very drug war policies that he did so much to establish.

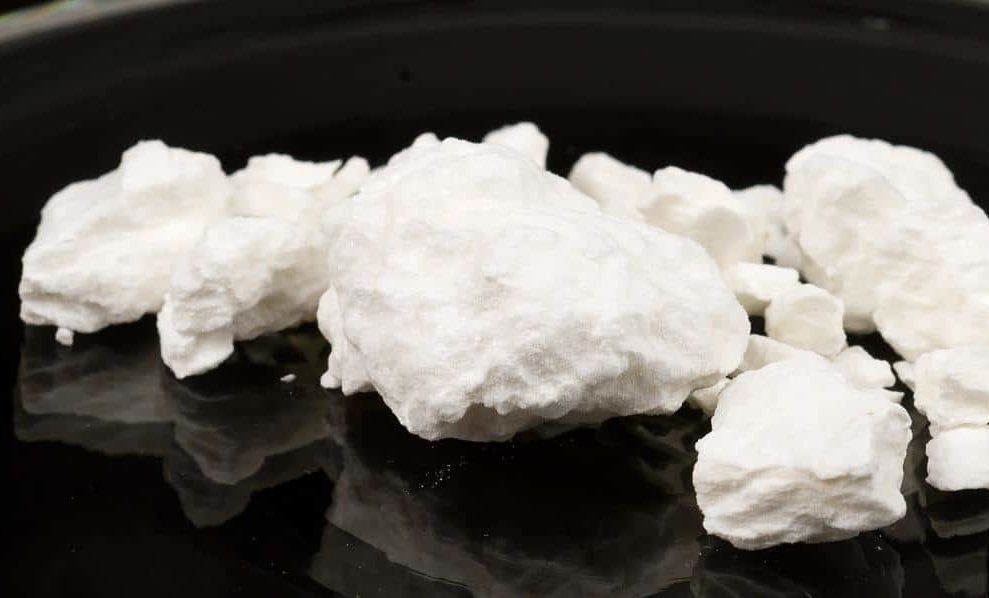

In 1986, Congress and President Reagan approved the Anti-Drug Abuse Act—authored by then-Senator Joe Biden. Amid the crack panic of that era, it determined that 1 gram of crack would be sentenced with the same severity as 100 grams of powder. Crack, it should be remembered, is just powder cocaine processed with baking soda and water. The main practical difference is that it produces a faster-acting, shorter high than powder, because it’s smoked.

Beginning in the 1980s, crack use was politically associated with Black Americans in urban areas. However, the majority of people who use crack are white. The far longer prison sentences for crack introduced in 1986 nonetheless targeted Black people.

The continuing impacts have been devastating. A 2015 federal prison report, for example, showed that more than a quarter (28 percent) of all people incarcerated in federal facilities were had crack convictions. The vast majority (88 percent) of this group were Black. And on average, crack charges resulted in sentences of over 14 years—longer than for any other drug.

In 2010, President Obama approved a bill that finally addressed this disparity—but only partially. It reduced the 100:1 ratio down to 18:1. No further action was taken until 2018, when President Trump approved the First Step Act. This didn’t further reduce the sentencing disparity, but made the 2010 reform retroactive. A person convicted for crack before Obama signed the new law could therefore qualify for relief and have their sentence reduced. The Marshall Project predicted then that about 2,600 people in federal prison would be eligible for earlier release because of the First Step Act.

“The obituary on this bill would be the greatest indictment of Washington that you have ever read.”

The window of opportunity for further reform is quickly closing. Next year, Republicans will take control of the House with a narrow majority. So it’s unlikely that the EQUAL Act—or even a compromise—will reach the House floor for a vote, let alone pass again.

“The thought that this would die at the last minute in a procedural machination in the Senate is unconscionable to me,” Holly Harris, president of the Justice Action Network, told Bloomberg. “The obituary on this bill would be the greatest indictment of Washington that you have ever read.”

Photograph via US Drug Enforcement Administration

Show Comments