For most of the nearly six years British Columbia’s overdose crisis has been declared a public health emergency, the consumption method linked to the most deaths has been smoking. Since 2017, smoking has been involved in more than 40 percent of BC overdose fatalities, nearly twice the prevalence of shooting or snorting deaths.

People who smoke their drugs are often less connected to harm reduction services than people who inject, and health authorities frequently overlook safer smoking resources, sometimes due to associating smoking with stimulants. But people smoke fentanyl, intentionally and unintentionally.

Canada’s safe injection and overdose prevention sites have generally been forced to exclude smoking spaces. Drug users and advocates have been calling for safe inhalation sites for years, which the provincial government has almost entirely failed to deliver. BC’s prescriber safe supply guidelines still don’t include any smokable options.

But at this moment, the province is sitting on a regulated supply of smokable diacetylmorphine—pharmaceutical heroin, commonly known as DAM—from a source that could fill prescriptions for at least several hundred people on an ongoing basis; potentially several thousand.

International treaties prevent Canada from cultivating commercial opium domestically, and importing DAM is such a highly regulated and expensive process that there’s no way to make it scalable.

Rather than buying a finished product, nonprofit pharmaceutical company Fair Price Pharma (FPP) used a federally licensed supplier to import the active pharmaceutical ingredients, which it will process into the final medication itself—allowing it to customize a safe supply option that’s not only lower cost, but specifically designed to be smoked.

Street supply heroin is traditionally DAM hydrochloride, the salt form that’s water-soluble and thus ideal for injecting. But it’s difficult to heat it to the point that it produces a vapor you can inhale. FPP’s base DAM doesn’t contain hydrochloride, so it vaporizes at a much lower temperature and can be easily smoked with a regular lighter.

FPP’s first 15-kilogram order was delivered in November, 2021. The plan is to formulate it into 3:1 DAM-to-caffeine mixtures packaged into sprinkle caps, designed to be opened and the contents smoked. The sprinkle caps will have a shelf life of six months and don’t need to be refrigerated, so FPP could ship them anywhere in the province—or further, local authorities permitting.

Since this is just a matter of combining ingredients, it’s not legally considered manufacturing, which means the product can be dispensed right away without waiting for a commercial license. Maintaining a supply line shouldn’t be a problem; the undisclosed European seller has guaranteed FPP up to 300 kilograms per year, which is far more than it has the capacity to use. FPP has already submitted import applications for two more batches, which Health Canada has already approved.

The next step is building the processing facility where the DAM gets formulated into the final product. FPP already has purchase orders on deck for the equipment and CA $1 million on standby from outside funders to set everything up, but the funders won’t release that money until FPP can guarantee an ongoing client base of at least 200 people—the number estimated to generate at least $1 million in sales.

“They want to see some guarantee they’ll get that money back,” cofounder Martin Schechter told Filter.

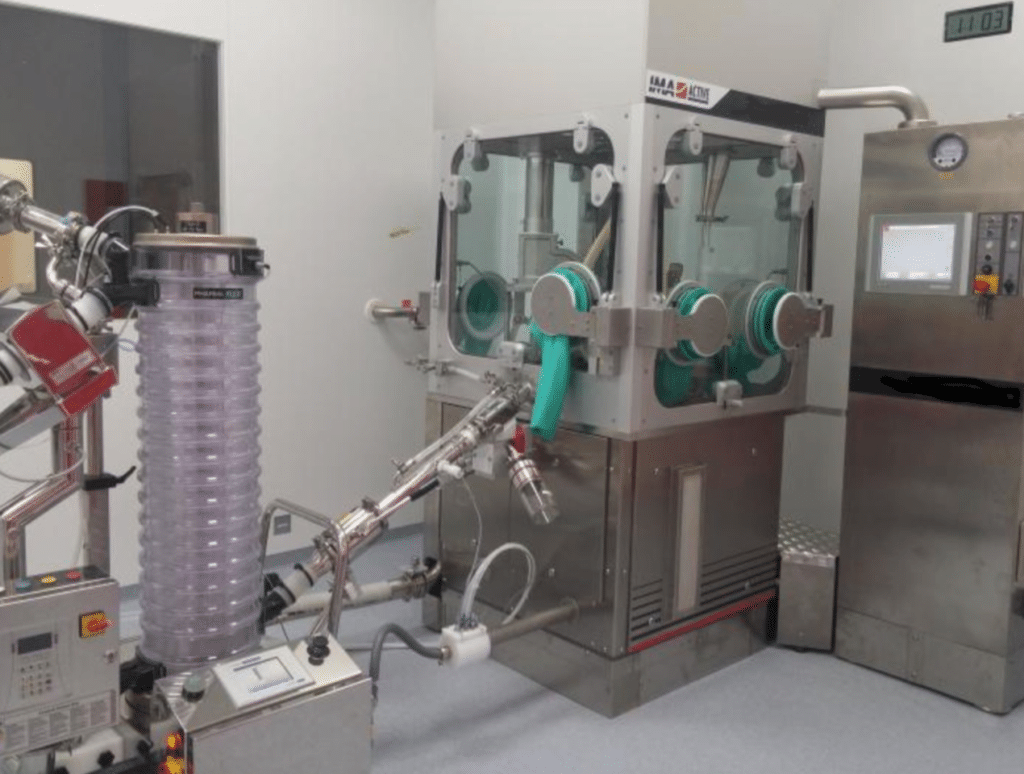

A high-containment encapsulator used to process potent substances such as DAM.

This is where the supply is stuck. The most direct path forward would be for the BC Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions (MMHA) to allocate funds, through grants or other means, to support at least 200 participants. FPP met with MMHA leadership in June 2021 and wrote to them when its shipment arrived in November, summarizing the situation and requesting a meeting. The Ministry still hasn’t responded, nor has FPP received any indication if or when it plans to.

(In response to Filter‘s inquiry on communication with FPP, the Ministry stated that “our government receives ongoing updates on their progress,” but did not elaborate further by publication time.)

“The provincial government is a big problem,” Schechter said. “So we are actually having to work kind of around the province right now.”

FPP can technically do this without further government authorization. But it has to reach the buy-in threshold piecemeal, through private donors and commitments from prescribers and drug user groups. None of the potential buyers need to pay up front, just reliably commit and then pay upon delivery.

FPP has commitments for 50 patients. It needs 150 more, or $750,000 or some combination of the two.

FPP has commitments for 50 patients so far. It needs 150 more, or around $750,000 in donations or some combination of the two. Once FPP gets the green light to build the processing facility, it can have the product ready for use within two to three months.

Several community-based groups have expressed interest in buying the supply, including Vancouver Coastal Health Authority and Victoria SAFER Initiative, two of the federally funded safe supply programs created during the pandemic.

SAFER started offering oxycodone tablets after patients pointed out that they’re easier to smoke than the hydromorphone tablets commonly provided, but what would be more ideal is a substance that’s actually intended to be smoked in the first place. SAFER is working to pilot a program offering smokable safe supply this year, but doesn’t know yet what that supply will be.

“Certainly powder DAM is one option we’re exploring, however we need to find an option that is going to fit with our timeline,” SAFER Project Director Heather Hobbs told Filter. “Supply chain and accessibility to the drugs we need are tied up in unnecessary bureaucracy and punitive regulatory structures that are not in line with an emergency response to the mass toxic drug poisonings.”

3️⃣When we realized folks who smoke their drugs didn’t have adequate options for #SafeSupply, we added oxycodone to our prescriber guidance.

That’s because people accessing the program asked for ‘the right drugs in the right doses for me’. pic.twitter.com/g7w69dWPRa

— Nurse Ranger 💊 (@CoreyRanger) July 16, 2021

Based on the price set by the supplier, and the operating and staffing costs of the processing facility, FPP could sustain someone at 400 mg DAM for $28 per day—substantially less than many people in BC are paying for equivalent street supply.

Drug user-led groups, including DULF and VANDU, are among those looking to buy in and will work to get their members access through prescribers if it comes to that. It’d be preferable to avoid a medicalized model and pay out of pocket, but the policy that allows FPP to sell its product without a commercial license also requires that people get a prescription before they can buy it.

FPP has formally expressed its interest in selling to DULF and VANDU directly, but only if the federal exemption they’re pursuing was granted and FPP fully sanctioned to sell them DAM without prescriptions.

A regulated pharmaceutical supply distributed through a non-medicalized model is what would actually begin saving lives immediately, the prospect of which the federal government does not seem to find motivating.

Whether people will get take-homes has not yet been determined.

“In the real world, right now, the only thing we can do legally is the model that FPP is pursuing,” Schechter said.

This places it out of reach for the majority of people at risk. Canada’s universal health care doesn’t mean everyone can easily access a doctor, and all of the community-level workers Filter spoke with emphasized how few providers are willing to prescribe safe supply. Many who do are at capacity; some medications have to be consumed under supervision, which makes it impossible to serve more than a small number of patients.

Whether people will be able to get take-homes of FPP supply or be subjected to supervised consumption has not yet been determined. The College of Pharmacists of British Columbia, which regulates pharmacy workers in the province, has hassled those working with safe supply prescriptions in the past. It’s unclear if take-homes might prompt it to interfere.

There are half a dozen legal pathways through which the federal or provincial government could facilitate access to the FPP supply, with prescriptions or without. But none seem likely happen in less time than it would take FPP to get there without them, even without knowing how much longer that would be.

📣For Immediate Release📣

OPEN LETTER to BC Minister of Health @adriandix re: Immediate and Expanded Access to Diacetylmorphine for People Who Use Opioids

Free the DAM!#bcpoli #SafeSupply https://t.co/v3N2wcAA1j pic.twitter.com/QioWRs14Xn

— HRNA/AIIRM (@HRNA_AIIRM) January 11, 2022

MMHA might not technically be blocking access to the DAM, but its inaction amounts to the same thing.

DAM, unlike many safe supply medications, has been a standard treatment for heroin use in multiple countries and has an overwhelming volume of evidence supporting it—even in Canada specifically. Schechter, who was the lead investigator on the pioneering North American Opiate Medication Initiative trial, said it stands to save more lives and more public funding than methadone.

All prescribed safe supply medications and pharmacy services are covered under the provincial public health care system, Pharmacare. But MMHA still hasn’t put DAM on the Pharmacare formulary. Access has been limited to a few hundred participants in the province’s clinic-based injectable DAM pilots. Which are critical and lifechanging services, but available to less than 1 percent of the people who could benefit.

MMHA itself has acknowledged DAM to be both medically and cost-effective in Canada, and especially in Vancouver. The Ministry provided Filter with comment outlining the province’s actions around safe supply, but ultimately did not address why DAM continues to be kept off the Pharmacare formulary even as medications useful to vastly fewer people, like fentanyl patches, are being added.

Political cowardice often compels health authorities to ignore DAM in favor of pharmaceuticals they can assure critics aren’t actual heroin, as their constituents meanwhile die by the thousands.

DAM being actual heroin is the point; it’s effective for so many people because it’s the supply they’re trying to use, not some other opioid they didn’t ask for but have to accept if they want something regulated. Hydromorphone tablets and fentanyl patches aren’t what a lot of the people using them would have chosen if they’d had options. Safe supply doesn’t keep people from using street supply just because the government updates a policy document to say so; it has to actually be the preferable option between the two.

Even through a medicalized model, FPP’s product could give hundreds of people their first smokable alternative to the street supply that may kill them. Advocates may also have the first DAM product that can be pushed onto the Pharmacare formulary. Commercial licensing will take at least another 18 months from whenever this initial version finally rolls out; the province may still have done nothing by then.

Top photograph by Ted McGrath via Flickr/Creative Commons 2.0. Inset images courtesy of Fair Price Pharma

Show Comments