On October 21, the International Drug Policy Consortium (IDCP)—a global network of 177 NGOs—released Taking Stock: A Decade of Drug Policy, a report on the past 10 years of global drug policies, in anticipation of the next United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs session, which will take place in March 2019.

Taking Stock assesses the status of the drug policy goals initially set by the UN in 2009, and continued at the 2016 United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) on drugs. It also evaluates how efforts to achieve those goals have impacted broader UN priorities such as “protecting human rights, advancing peace and security, and promoting development.”

In 2009, the UN set five priorities, which targeted illicit drugs’ global cultivation, production, manufacture, trafficking, marketing and distribution through prohibitive and repressive measures. The results have been catastrophic, concludes the report.

“Not only has drug prohibition failed to reduce drug demand and supply,” says Hannah Hetzer, senior international policy manager for the Drug Policy Alliance, an IDCP member, “it has left a series of disastrous impacts on human rights, health and economic development in its wake.”

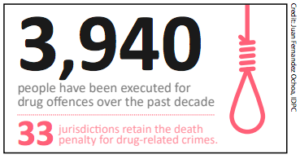

Use of the death penalty in 33 UN jurisdictions, extrajudicial killings of people who sell and use drugs in Southeast Asia, and mass incarceration for drug-law violations are just a few examples of the human rights abuses enabled by global drug policy in the past 10 years.

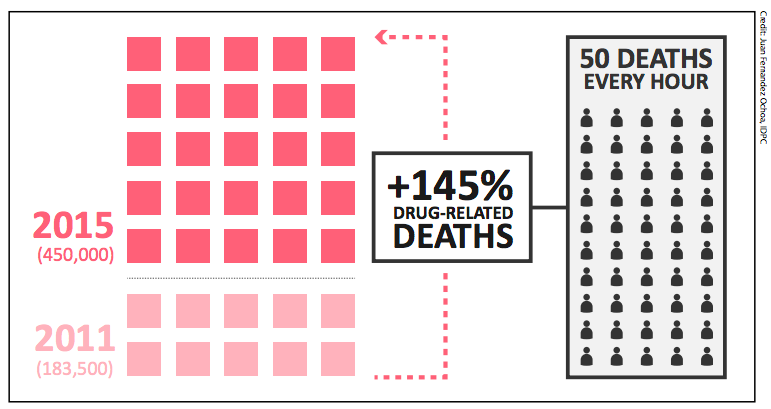

Additionally, the global dearth of harm reduction services threatens people’s rights to health: Drug-related deaths have increased by 145 percent over the last decade; there were 450,000 in 2015.

Drug-war policies have also undermined the UN’s commitment to promotion of peace and security—causing and exacerbating violent conflicts over drug supply and distribution in places like Mexico and Afghanistan. And eradication of illicit crops has hindered development in Latin America and other regions.

In addition to addressing such issues, the report suggests revising the methods used to measure the efficacy of global drug policy going forwards. Evaluations, according to the IDCP, should be conducted more frequently, more thoroughly, and on local, national and international scales. Plus, data should not solely be drawn from the same government that is implementing drug policies. And the evaluation of drug policies must take into account their effect on the health of people who use drugs—not just their effect on the drug trade.

It remains to be seen how the IDPC report will impact the 2019 UNCND meeting. But as it concludes, the overall intent behind the past 10 years of global drug policy—the quest for a “drug-free world”—is “unrealistic and unachievable.”

Indeed, the report reveals this desire—echoed in US drug policy initiatives like Drug-Free Communities—to be an inherently violent one, one that aims to divorce people from their bodily autonomy rather than support their health.

Photo via International Drug Policy Consortium (IDCP) report: Taking Stock: A Decade of Drug Policy.

Show Comments